This feature was published in conjunction with the screening of The Affairs of Anatol at SFSFF 2025

DeMille’s film transposes the original Viennese setting of Arthur Schnitzler’s 1893 play to contemporary New York, with nods to some design trends of the early 1920s. The framing episode starts with a luxurious Japonisme-style boudoir featuring stylized cherry and plum blossom floral motifs and screens with a touch of Art Nouveau, in contrast to the masculine Arts and Crafts furniture glimpsed in the parlor. Later, New York night life beckons at a midnight café, The Green Fan, whose exterior is a grandiose miniature of Paris’s Beaux-Arts Petit Palais from the 1900 Exposition Universelle. Inside, a large fan-shaped screen changes the atmosphere on stage while fashionable revelers dance and diners study an illustrated oval fan menu.

JAPONISME

The opening of the mysterious island kingdom of Japan to the West in the 1850s was a revelation for the arts. By the late 19th century, Japonisme had spread to America from France, and DeMille himself had already featured sliding screens, incense burners, and kimonos in his 1915 smash hit The Cheat. Bold woodblock prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige influenced European artists like Van Gogh, Monet, and Toulouse-Lautrec, and James McNeill Whistler designed a magnificent Anglo-Japanese Peacock Room in London in the mid-1870s that was later transported to America (it’s now in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.). When Gilbert and Sullivan’s satirical operetta The Mikado premiered at London’s Savoy Theatre in 1885, its opening lyrics sang of the passion for all things Japanese (“on many a vase and jar, on many a screen and fan”). London luxury goods shops like Liberty carried Japanese textiles, screens, and lacquered furniture; and rich silks, kimonos for men and women, tea rooms, prints, ceramics, and pottery seemed to be everywhere.

FROM JEWELS TO GINGHAM

The main focus in the first episode of Anatol is jewels. In his quest to rescue former school sweetheart Emilie from the clutches of her sugar daddy, a floral-themed diamond necklace is a brazen symbol of her downfall. A frustrated and indignant Anatol smashes up her parlor stuffed with expensive furnishings, including a set of Louis XIV chairs. Then it’s back to simplicity in the second episode, with the seeming innocence of the countryside betrayed by Anatol’s next reform target, a simple wife in stereotypical gingham who dreams of nothing but stylish finery.

A GOTHIC LAIR

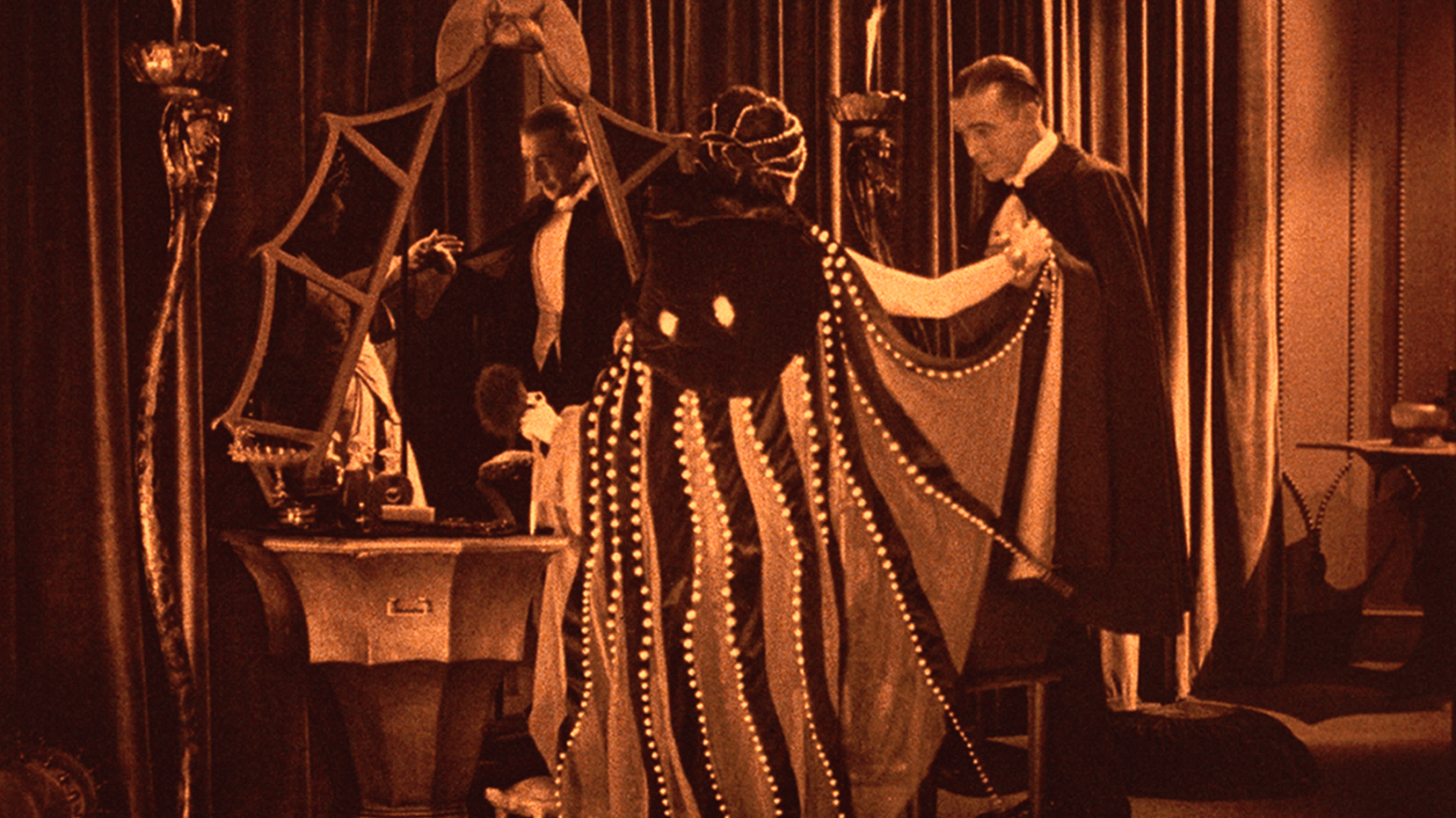

The Satan Synne episode, a Faustian fantasy, finds Anatol in the lair of a Broadway vamp. The decadent décor is crammed with Gothic bat motifs (note the dressing table and mirror). There’s also a bed with serpent metalwork, guarded by a languid leopard, and a handmaiden straight out of Ancient Egypt or Babylon. Synne daubs her lips with Le Secret du Diable, and when Anatol is offered hallucinogenic absinthe as an aperitif, he sees himself reflected in the mirror as a skeleton. The dark atmosphere evokes literary predators as well as filmic: Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula; Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 novella, Carmilla, and Rudyard Kipling’s 1897 poem “The Vampire,” both about female vampires; and Theda Bara’s heartless seductress in the 1915 film, A Fool There Was, an allusion audiences of the time would surely catch. When Synne embraces Anatol wearing her Octopus gown and voluminous cloak, the black velvet and pearl tentacles seem to devour him.

COSTUMES BY CLARE WEST

The spectacular Octopus ensemble, and most of the film’s clothes, are credited to Famous Players-Lasky’s resident designer Clare West, who not only worked on Griffith’s epic Intolerance and Theda Bara’s Cleopatra, but kept up to date on the latest haute-couture with regular forays into Paris and New York. When Swanson’s character tells her maid to get out her “lowest gown and highest heels,” West easily supplied the chic allure and know-how. Many of the film’s fashions are mid- to-late Teens—not yet the Roaring Twenties—with loose-fitting silks and wool jersey, and soft hats and plumes; but there are also stylish velvets, chiffon, sequins, and pearls, and a haughty ermine wrap. We see ample evidence of all those shopping trips: some clothes are reminiscent of French designer Paul Poiret, famous for freeing Parisian women from their corsets, and avant-garde artist Sonia Delaunay’s geometric designs on velvet. Fashion is always front and center, and not just in the finery for stepping out on the town; when Swanson sinks into ruffled circular cushions on the daybed in her alcove, she wears an array of uber-feminine negligees and robes. Let’s not forget Wallace Reid’s impeccably tailored wardrobe, menswear with panache, which ranges from smart leisure suits with plus-fours to full evening attire with cape and top hat. Were they made in Hollywood by imported New York or London tailors?

ART DIRECTION BY PAUL IRIBE

Anatol’s exquisite pictorial art titles were created by the film’s French-born art director Paul Iribe, who went on to design several more films for DeMille. Iribe was truly a “jack-of-all-arts,” and master of all of them. He began his career as a cartoonist and illustrator, studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts, drew models for Paul Poiret, befriended a young Jean Cocteau, designed furniture, jewelry, clothes, and shoes, and had his own interior design firm. After falling out with DeMille, he returned to Paris. Years later, he was due to marry Coco Chanel but had a fatal heart attack on her tennis court on the Riviera.