A Special Presentation by John Canemaker

By 1910, live-action short films and hand-colored magic lantern slides ruled the movie screen, but animation, maybe not so surprisingly, was in eclipse. Expensive and time-consuming, cartoon work was not terribly well suited to the hectic pace of the nickelodeon’s insatiable demand for product. Nevertheless, two extraordinary men stand out. One, in Paris, was Émile Cohl. The other, in New York, was Winsor McCay.

At the time, McCay was best known for his brilliant Little Nemo comic strip. In each fantastical episode, Nemo is caught in an escalating tangle of weirdness amid a psychedelic succession of ice caves, Italian palaces, and Art Nouveau gardens. The strip made McCay a celebrity, Nemo becoming so famous that Victor Herbert even composed a Broadway operetta about him. And so, in 1910, having conquered the Sunday comic page, McCay set his sights on drawing him for the screen.

McCay’s first idea was to take Nemo and his friends on the vaudeville stage where he animated them as part of a live act, introducing them on stage with quickly drawn “lightning” sketches and then speaking over hand-colored moving images. Within a year, he returned to the stage with a far stranger, delightfully gruesome insect-giant. This was a bloodthirsty New Jersey mosquito called the Jersey Skeeter, another veteran comic strip character who had appeared in several pre-Nemo series by McCay. As with Nemo, this film also had an elaborate live-action prologue, now lost. But it’s the animation of the blood-sucking mosquito that provided the revelation, putting McCay’s uncanny feel for weight and comic timing on display. As John Canemaker notes in his biography of McCay, this is an insect who thinks and considers solutions to problems. Just as remarkable, McCay gives him a certain amount of comic charm, as he hesitates and makes eye contact with us before gleefully quenching his thirst. Here, it can be argued, is the freakish origin of personality animation.

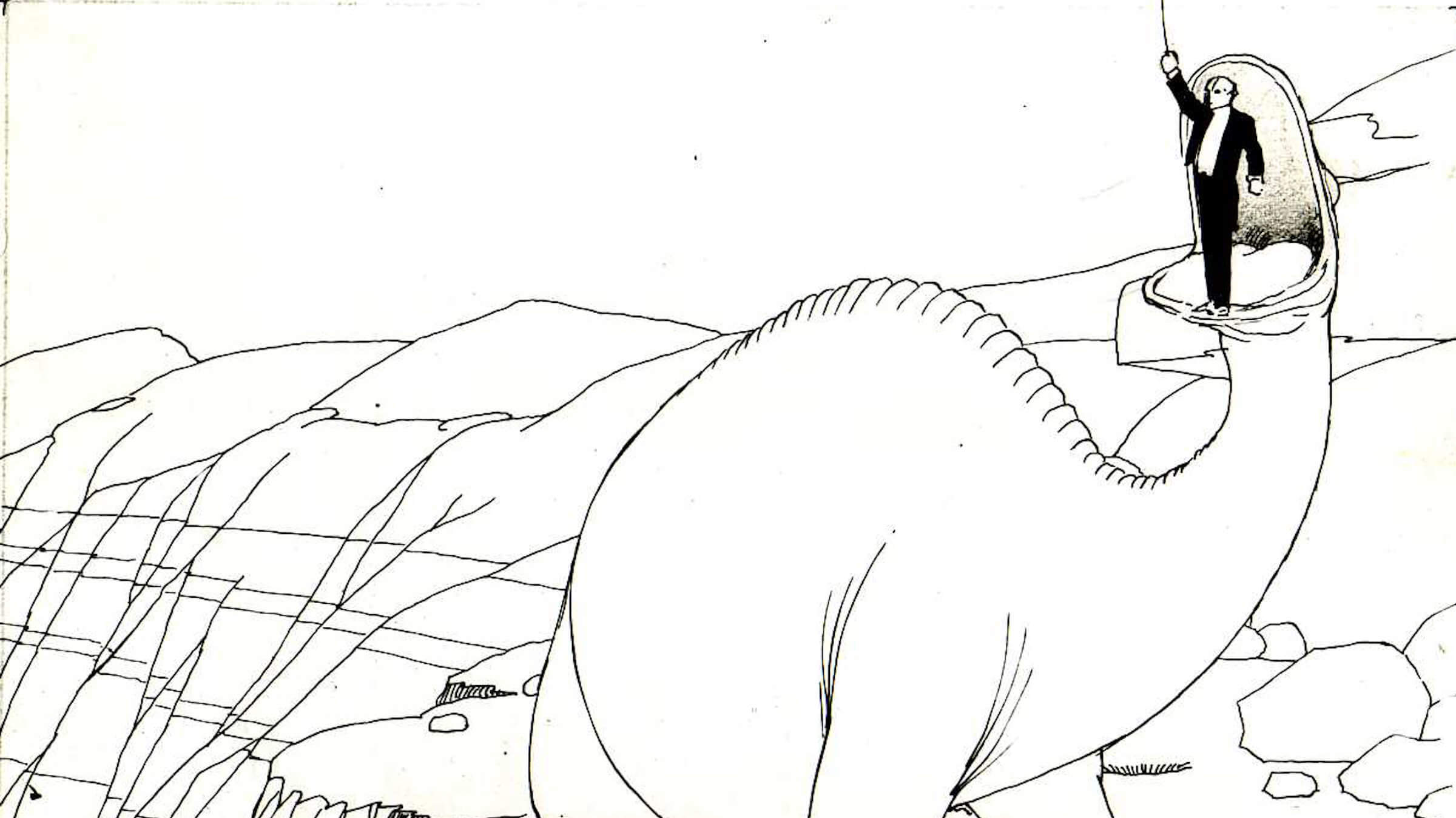

Within a year, however, the Jersey Skeeter was eclipsed by McCay’s masterpiece, the inimitable Gertie the Dinosaur, who was a sensation from the start. A genial dinosaur inspired by the skeleton on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, Gertie is unique in early animation for her charm and temper. Film historian Scott Bukatman calls her a loveable rogue —“prankish, unruly. Unruly rather than monstrous … Gertie the Dinosaur, not King Kong.”

True, Gertie was, like Nemo’s friends and the Jersey Skeeter, originally part of yet another McCay vaudeville act. But as Donald Crafton and David Nathan have noticed, the film was conceived differently from McCay’s earlier cartoons. The earlier shorts are part of illustrated lectures; Gertie is part of a multimedia dramatic performance, with McCay playing the part of her trainer. They interact and indulge in back-chat: he talks to her, she responds like a mischievous pet. He cracks his whip; she cries. He tosses her a pumpkin (or apple); she gobbles it up.

Spatially, too, Crafton and Nathan note, Gertie was McCay’s most complex film to date. In Little Nemo, characters romp on black-and-white backgrounds; in The Story of a Mosquito (a.k.a. How a Mosquito Operates), the only background is the body of the sleeping victim. But in Gertie, his protagonist is anchored in a mountainous environment that resembles a theatrical stage set, rendered in depth and in some detail. Working with rice paper rather than transparent cels, McCay and his assistant were obliged to provide those backgrounds in each of the drawings, retracing them somewhere between 2,500 and 3,500 times.

McCay the workaholic insisted on animating the hard way, taking a minimal number of shortcuts. Yet his singular genius for design and timing sometimes obscures his pioneer work in creating standard techniques today, including the pose-to-pose system whereby sequences are divided into “extremes“ and “in-betweens“ (he called it the “split system”) for more clarity of movement. Nor was he immune from cycling movements (as when Gertie dances on her hind legs) or filming on “twos“ and “threes“ (shooting the same image twice or three times) when the occasion called for it.

Gertie became a star, and McCay not only took his act on the vaudeville circuit but also performed with her in banquet halls for large gatherings of newspaper colleagues and socialites. William Fox, the fledgling film distributor, was sufficiently taken with Gertie that he contracted with McCay to enlarge the film by adding a live-action framing narrative, more than doubling the running time of McCay’s original. This is the version that survives today, in which a live vaudeville audience is replaced by a cast of comic strip artists who attend a banquet and watch McCay take on a bet by fellow Hearst cartoonist George McManus. We then see McCay with his assistant (played by his son Robert) in what became a scene—later revered by Disney—showing the epic labor involved in creating a cartoon. It is this version that opened at the Wonderland Theater in Kansas City on Saturday, December 19, 1914, toured Kansas, and then spread across the country.

After the success of Gertie the Dinosaur, McCay continued to make handcrafted, highly individualized animated shorts built around cartoon characters. But his last great short marked a startling change, part of the direction his career as a newspaper cartoonist had taken at The American. By the time the First World War came to America, McCay not only dominated Hearst’s Sunday comic page, he had also become one of Hearst’s leading political cartoonists, satirizing slumlords, political bosses, and plutocrats. Most notably, though, even before the United States entered the war, he followed Hearst’s lead in making the eagle scream, attacking Germany and its allies. When he returned to animation, McCay was determined to dramatize what was considered the Kaiser’s most notorious atrocity to date—the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine.

He threw himself into his work, pouring his own money into the movie and taking two years to complete it. He also devised a new technique. Instead of rice paper for character drawings, which required backgrounds drawn on each sheet, McCay, for the first time, drew on celluloid, soon to be the preferred medium of commercial animators. Canemaker estimates that by the time McCay finished the film he had completed about 25,000 drawings (little more than ten times the amount, according to the most recent estimates, of what was required for Gertie). In the process, it is arguable that he became the first to use animation for political propaganda.

McCay’s work embodies the road rarely taken —that of the individual artist, working more or less by himself outside the studio system. The road American animation did take, of course, was chosen by the Hollywood studios, which treated it as an entertaining novelty made to precede the feature —so-called “Grouch Chasers,” populated mainly with comic strip characters like Maggie and Jiggs, the Katzenjammer Kids, Buster Brown, and folks from Fontaine Fox’s Toonerville Trolley. In retrospect, McCay occupies a unique position: America’s first animation auteur, the peerless draftsman who made manifest the artistry lurking behind comic and not-so-comic American cartoons.

THE FILMS

Little Nemo (Vitagraph, 1911) Animated, written, hand-colored, and directed by Winsor McCay. Characters adapted from McCay’s Sunday comic strip, Little Nemo in Slumberland, which ran in the New York Herald. Live-action sequence director unknown. With John Bunny, George McManus, and others.

How a Mosquito Operates (Vitagraph, 1912) Animated sequence animated, written, and directed by Winsor McCay. Based on a character taken from McCay’s comic strips, including Dream of the Rarebit Fiend.

Gertie the Dinosaur (Box Office Attractions, 1914) Animated sequence animated, written, and directed by Winsor McCay. Backgrounds by John A. Fitzsimmons. Live-action sequence director unknown. Camera room assistant: Robert McCay. With Winsor McCay, George McManus, Tad Dorgan, Roy McCardell, and Tom Powers.

The Sinking of the Lusitania (Jewel Productions, 1918) Animated, written, and directed by Winsor McCay. Assistants: John A. Fitzsimmons and William Apthorp Adams.

Presented at SFSFF 2013 with live music by Stephen Horne