For such a professionally modest filmmaker—“I just want to make a tray of good tofu,” is the oft-quoted self-assessment—Yasujiro Ozu generates a surprising amount of critical discord. Is he a neorealist or a formalist? Radical or conservative? The most or least Japanese of Japan’s filmmakers? Western audiences discovered Ozu’s postwar films after the director’s death in 1962 and the enthusiasm for melancholy domestic dramas like Tokyo Story (1953) often bordered on reverential. Some Western critics saw in Ozu an enigmatic exemplar of the exotic East, like a sort of walking tea ceremony. In Japan where Ozu’s films had been making top ten lists since the 1930s, the critical appreciation is just as strong but less awed. In a 1984 soft porn nicknamed Late Spring: The Sequel (after Ozu’s 1948 film), the director applied Ozu’s familiar postwar aesthetic: a low angle, static camera; no dissolves or close-ups; frontal framing of actors during dialogue scenes rather than the classic three-quarter view; shots of empty landscapes as transitions between scenes.

But as Ozu silent films have come to light critics have had a harder time. Film historian Tony Rayns writes, “They discovered that Ozu’s tofu recipes were more varied than previously imagined.” Critics struggled to square the jazzy gangster dramas and scatological comedies, peppered with Hollywood references, with Ozu’s later work. Which is the real Ozu? The mature director who left comedy and gangsters behind to focus on, in historian Donald Richie’s words, “The dissolution of the traditional Japanese family”? Or was the true Ozu the energetic, try-anything filmmaker of the 1920s? An Inn in Tokyo is a crucial step in Ozu’s evolution to his postwar style. The director combines silent-era melodrama with his postwar formalism, while interjecting almost abstract transition shots between scenes of social realism. Watching the film, we understand the two Ozus were always one.

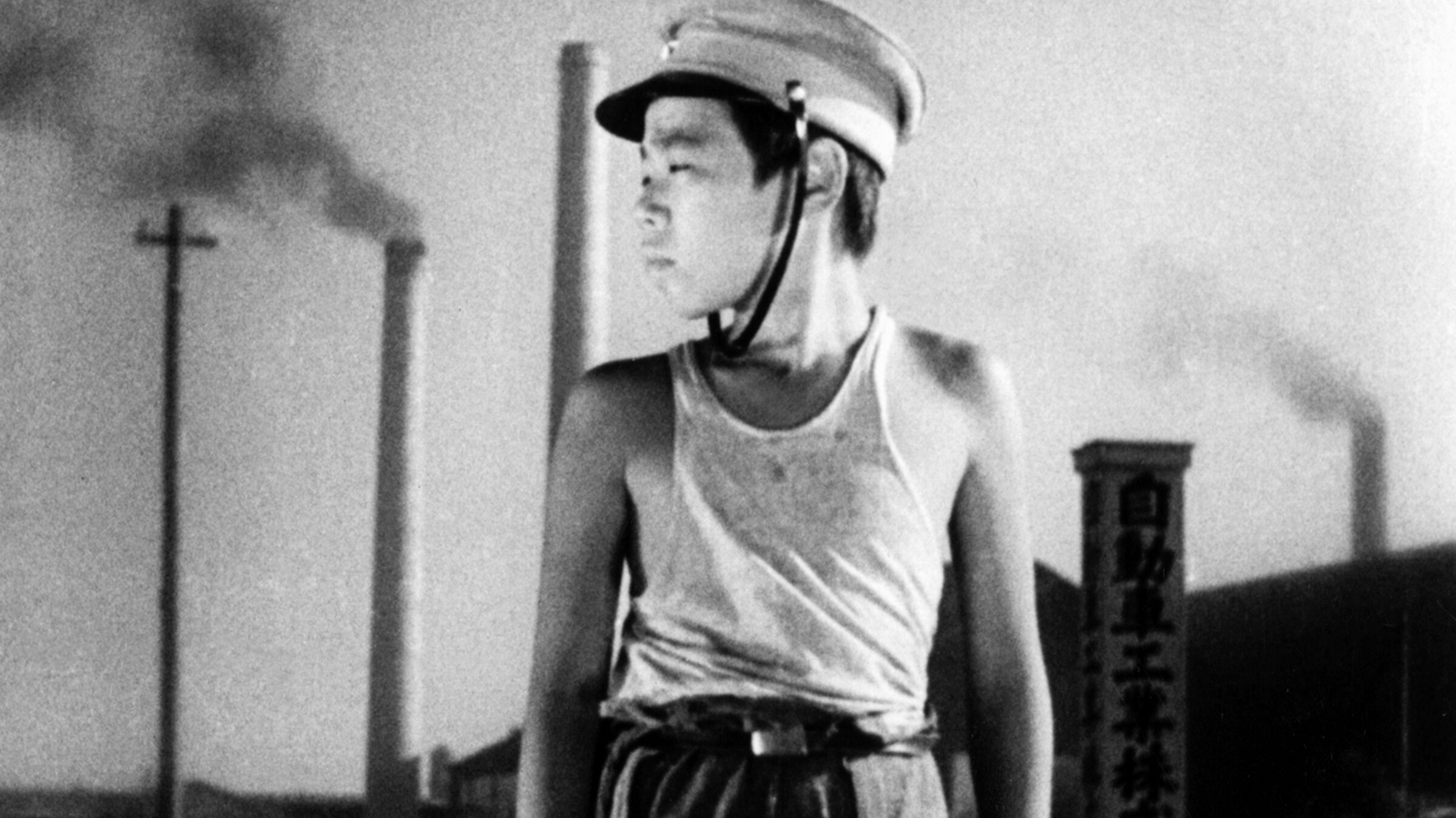

An Inn in Tokyo (Tokyo no yado), made in 1934, is the story of a down-and-out laborer looking for work with his two young sons in tow and his encounter with a woman and her daughter in similar circumstances. The Great Depression is on, which in Japan meant skyrocketing unemployment, in addition to the political unrest characterized by what one contemporary journalist called “government by assassination.” Kihachi, the father, wanders Tokyo’s industrial zone, a barren landscape of giant abandoned spools, water tanks, and endless telephone poles. The elegance of these carefully composed industrial still-lifes is a form of understatement; Ozu doesn’t beat viewers over the head with the pathos of the family’s desperate straits. The film is often compared to The Bicycle Thief, and like De Sica’s film it acutely observes the grinding details of poverty, the miles trudged in the faint hope of a job, the boredom of empty hours with nothing to eat and no place to go, the eternal struggle to keep up one’s spirits.

Ozu used a character named Kihachi in three other films, always played by Takeshi Sakamoto: Passing Fancy (1933), The Story of Floating Weeds (1934), and An Innocent Maid (1935). Throughout his film career Ozu recycled themes, situations, and character names and Inn plays like a somber sequel to Passing Fancy (it helps that child star Tokkan Kozo plays Kihachi’s son in both films). Both Kihachis are laborers raising children and both develop an inopportune attachment to women on the margins. The big difference is that the Kihachi of Passing Fancy is employed. Lost along with job and shelter in Inn are the comic touches and the presence of a community—friends, fellow workers, even passersby—that leaven the earlier film.

Although Inn takes place in the big city, Kihachi and his sons might as well be on an abandoned planet, chasing the stray dogs for the bounty that will buy them a meal or the next night’s lodging in the cheap boarding house of the title. The two brothers’ antics, comic in films like I Was Born, But…, here have dire consequences. In one scene the boys fight over who should carry the sack of goods Kihachi has left in their charge and end up leaving the bundle in the middle of the road, each too stubborn to back down. As the brothers face off across a deserted road with the family’s only possessions between them, Ozu’s low angle makes them monumental, like gunfighters squaring off in a spaghetti western. The director’s goal in his films, as he stated late in life, was “to make people feel without resorting to drama.” By 1934 he had already achieved it.

One of the most striking elements of Inn is Ozu’s use of transition shots, a relatively new addition to his stylistic repertoire. At one point the family’s dreary wanderings abruptly cut to a gorgeous shot of smoke trailing horizontally across the screen; a woman’s profile is followed by a sky bursting with fireworks, a dazzling quasi-abstract moment. Critic Noël Burch coined the phrase “pillow shots,” to describe this device, defining them as superfluous to the narrative. The phrase references a Japanese poetic form, “pillow words,” a kind of verbal buffer between ideas. Japanese critic Tadao Sakao, on the other hand, calls these same shots “curtain shots,” linking them to Western theatrical tradition. In Inn the shots are an echo of the gangster films’ razzle-dazzle; the transition shots of the postwar films call much less attention to themselves. They’re also a reminder that Ozu’s formal techniques, even in the silent era, were in dialogue with the emotional content of his films. Here the shots interrupt the tunnel vision that poverty and homelessness create with a reminder of a wider world.

Ozu wrote Inn’s story with frequent collaborators Tadao Ikeda and Maso Arata, using the pseudonym “Winthat Monnet,” or “without money.” Indeed, according to An Ozu Retrospective, a commemorative filmography published in Japan in 1993, Ozu was worried about his financial situation, mentioning it frequently in his diary at the time. The shoot was interrupted by army service and it was a time of upheaval in the director’s life in other ways as well: Ozu’s father had died the previous year and the Shochiku company, where Ozu had worked since he was nineteen, was planning to move its studio from Kamata to Ofuna, about thirty miles away from the noise of Tokyo’s factories. They needed a quieter environment to make talkies.

Inn was the director’s penultimate silent and Ozu had jokingly vowed to “film the last fade-out of the silent cinema,” according to film historian David Bordwell. The studio heads at Shochiku, meanwhile, applied pressure on him to hurry up and direct a sound film. To complicate matters, the director had promised his cameraman, Hideo Mohara, to only use his proprietary recording system, but Shochiku had a contract with Tsuchihashi Sound. Ozu wrote in his diary around the time of making Inn, “I made Mohara this long-held promise. If I want to keep this promise, I may have to quit directing. That would be fine with me too.”

In his impulse to toss away his career, critics have suggested Ozu is not unlike his protagonist Kihachi, the father who struggles to accept parental responsibility. Early in his career Ozu had resisted professional advancement: “As an assistant I could drink all I wanted to and spend my time talking,” he once recalled. “As a director I’d have had to stay up all night working on continuity.” Obstinate in the face of change, he was not only famously reluctant to adopt sound, he also later avoided color and refused even to consider widescreen (“It reminds me of a roll of toilet paper”). This resistance extended to the thematic and emotional content of his films. In 1933, he addressed himself in his diary, “Kiha-chan! Remember your age. You’re old enough to know it’s getting harder to play around with ‘sophisticated comedy!’” Inn in Tokyo’s somber fatalism is a sign the director took his own advice

.

Presented at SFSFF 2008 with live music by Guenter Buchwald