“Our Lady of the Spasms,” was the label critic Nino Frank famously gave to Pina Menichelli for her writhing poses and sudden movements. Her performances, at once dated and strikingly modern, are preserved in the amber tinting and toning characteristic of the so-called “second period” of silent cinema. Falling between Méliès’s “trick” films and the narrative model familiar to viewers today, the films of this second period, as historian Nicola Mazzanti observes in the journal Film History, “seem to constantly hint at other solutions, other alternatives to that cinema we now consider classical.”

Il fuoco (The Fire) is such a film, a mix of motifs both familiar and forgotten. On the familiar side, it features Menichelli in one of the earliest appearances of the iconic femme fatale and belongs to the celebrated diva genre, an Italian precursor to Hollywood’s star system. Less familiar to contemporary viewers are its choices of spectacle over continuity and stylized gestures over naturalistic acting. Its dazzling rainbow of tints and tones reminds us that we are no longer in the black-and-white Kansas of classic Hollywood cinema, and the film packs an extraordinary amount of melodramatic action into its not-quite feature length.

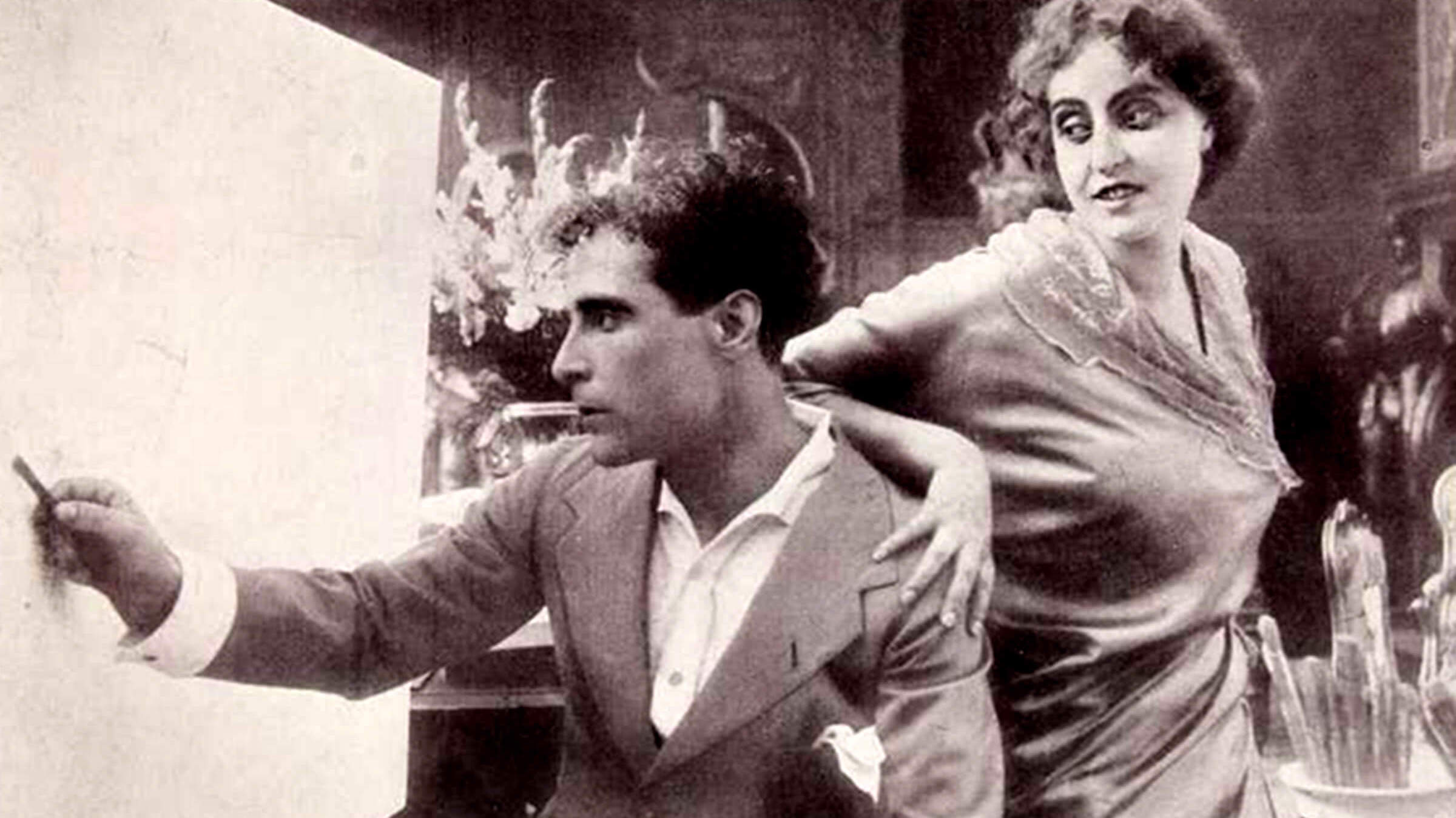

Pina Menichelli plays a rich and powerful poet—the credits identify her character simply as “She”—who seduces then abandons a naïve painter played by Febo Mari, who also cowrote the script. Menichelli’s sexually aggressive poet seems more at home in the liberated world of Sex and the City than the patriarchal, ultra-Catholic Italy of 1915, where women couldn’t vote or get a divorce. Her motivation, as she toys with the painter, remains as obscure as her screen presence is mesmerizing. Critics have taken pains to distinguish the Italian diva from her sister, the vamp. “The vamp is more calculating in her devastation, the woman who lives off the unhappiness of her victims,” wrote Nino Frank in 1954. “The Italian femme fatale is guided toward a destiny often as redoubtable for her as for others.” A distinction that means little to the poor painter dazzled by Menichelli’s poet.

The Sicilian-born daughter of a theatrical family, Menichelli had been working in film since 1912 but didn’t ascend into the company of sister divas Francesca Bertini and Lyda Borelli until Il fuoco appeared. A phenomenon unique to Italy in the second decade of the 20th century, “diva” described not only these influential and well-paid actresses but also a genre of films, in which they generally played tormented women who, in the words of historian Gian Piero Brunetta, “[are] at once priestesses and conscious victims of all the rites of Eros.”

Although largely forgotten today, the divas were as powerful offscreen as their on-screen characters were powerless. (Menichelli’s poet is the rare exception to this rule). Lyda Borelli, whose 1913 Ma l’amor mio non muore (Everlasting Love) is often cited as the first diva film, inspired adulation. Her hordes of admirers copied her dress, her hair, her very gestures. A new word—borellismo—was coined to describe their fandom. In 1919, Francesca Bertini signed a contract to make eight films for 2,000,000 lira, a record sum for the day. Film historian Vernon Jarrat describes how Menichelli negotiated her own fees: “If [the producer] began to show any signs of rebellion Menichelli would promptly and ostentatiously begin to pack her numerous trunks preparatory to seeking her fortune abroad.”

Yet if their salaries and outsize personalities link them to modern stars, their stylized acting harkens back to their 19th century opera namesakes. “She enters into the picture as if to perform a solo,” wrote film historian Pierre Leprohon, “which everything else, down to the smallest detail, must help to emphasize.” Like those of her operatic predecessors, the diva’s performance bore little relation to the naturalistic acting that later dominated cinema. Even during its heyday, the diva style was mocked. In 1918, novelist Colette skewered common diva clichés in the magazine article, “A Short Manual for the Aspiring Scenario Writer”: “Q: What happens to the femme fatale at the end of the sensational film? A: She dies. Preferably on three steps, covered by a rug. Q: And between the apotheosis and the fall of the femme fatale, isn’t there room on the screen for numerous passionate gestures? A: Numerous, to say the least. The two principal ones involve the hat and the rising gorge …. When the spectator sees the evil woman coiffing herself with a spread-winged owl … he knows just what she is capable of.”

In fact, Pina Menichelli’s poet in Il fuoco signals her predatory nature with an owl hat and a love nest referred to as “Owl Castle” in the intertitles. Director Pastrone, who had established his credentials as a master of spectacle with 1914’s Cabiria, gives the poet and painter a lavish set in which to love and suffer. Part of the pleasure of Il fuoco, then and now, is the luxurious ambiance of the poet’s castle, with its staff of discreet servants and Menichelli’s elaborate gowns and jewels (who designed that astonishing hat?), all captured in richly tinted photography.

The film’s complex color scheme was characteristic of Italian film of the late teens and the result of two separate post-production coloring processes. Toning affects the shadows of the film frame, while tinting colors the highlights. As dramatic emphasis rather than naturalism was usually the goal, the results may seem odd to modern filmgoers. In the world of Il fuoco, a garden can be blue, green, or pink, or possibly all three in succession. Segundo de Chomón, who photographed Il fuoco, got his start coloring films for Pathé and experimented with color effects his entire career. The festival is screening the 1991 restoration print, which followed the film’s original production notes on color and used toning and tinting techniques of the time.

An expensive process, toning diminished dramatically in the early 1920s (tinting survived a little longer), which also coincided with the end of the diva era. Like paleontologists who dispute why dinosaurs disappeared, film historians disagree about what exactly snuffed out the women writhing, fainting, and even dying on Italian screens. The various explanations offered—that focus on the diva stunted the development of other aspects of filmmaking or that the divas were too expensive—imply that the divas were crushed by the weight of their own excess. Indeed, film historians writing during the ascendancy of neorealism even blame the divas for the collapse of the Italian film industry at the end of World War I, as if these femme fatales had the power to lead not only men but whole industries to their doom.

Menichelli, like Borelli and Bertini, used her diva stardom as a stepping stone to marriage into the Italian aristocracy. In 1924, she married Baron Carlo D’Amato of Rinascimento Film, the studio where she had worked since 1919, and immediately retired. Although she later destroyed all documents and photos related to her film career, she could not erase herself from history. In the 1950s, surrealist painter Salvador Dali recalled a classic moment from Menichelli’s second diva film Tigre reale (Royal Tiger, 1916), in which she chews a flower from a bouquet: “In those days, characterized by such violent eroticism, palms and magnolias were bitten off and devoured by these women whose frail and sickly look did not rule out corporeal shapes thriving on a feverish and precocious youth.”

Preceded by the orphan film Origin of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” (1909)

Presented at SFSFF 2011 with live music by Stephen Horne