The Black Pirate is the epitome of motion picture art and science in the Hollywood of the 1920s. Whereas previous Douglas Fairbanks productions such as Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood (1922) and The Thief of Bagdad (1924) employed size and scope to push the limits of cinema production, The Black Pirate used the nascent technology of two-color Technicolor, demonstrating Fairbanks’s leadership within the movie industry. He alone at the time possessed the artistry, vision, and financial resources to shepherd to completion a feature-length silent film designed entirely for color cinematography.

Technicolor’s red and green process gave the Fairbanks swashbuckler an added dimension and proved to be a vital step in the development of this burgeoning technology. In addition, Technicolor’s inherent limitations and high cost had the effect of unfettering the picture from pageantry and visual effects, resulting in a straightforward action-adventure film. The picture was a refreshing return to form for Fairbanks and a dazzling new showcase for the actor-producer’s favorite production value: himself. The actor is resplendent as the title’s bold buccaneer, buoyed by a production brimming with rip-roaring adventure and exceptional stunts and swordplay, including the celebrated “sliding down the sails” sequence, arguably the most famous set piece of the entire Fairbanks treasure chest.

As a child, Fairbanks had been interested in pirate lore and played pirate, most often relishing the role of Captain Kidd. He had first contemplated a film involving pirates in 1922 for his sequel to The Mark of Zorro (1920). However, in the back of his mind, he felt that to do a pirate story justice necessitated color cinematography rather than the standard practice of applying tints and tones to black-and-white film. “Personally,” he wrote in 1925, “I could not imagine piracy without color.”

Two-color Technicolor was still a novelty and had appeared only in sequences of big-budget films such as The Ten Commandments (1923), The Phantom of the Opera (1925), and Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925)—sequences that Fairbanks thought garish. The Black Pirate was the first major Hollywood film designed totally for color in which the experimental process was first carefully tested. Even though the Technicolor aspect of the production was a questionable selling point with audiences, Fairbanks was confident that his compositions—created in an almost painterly fashion—would win over the public to color motion pictures.

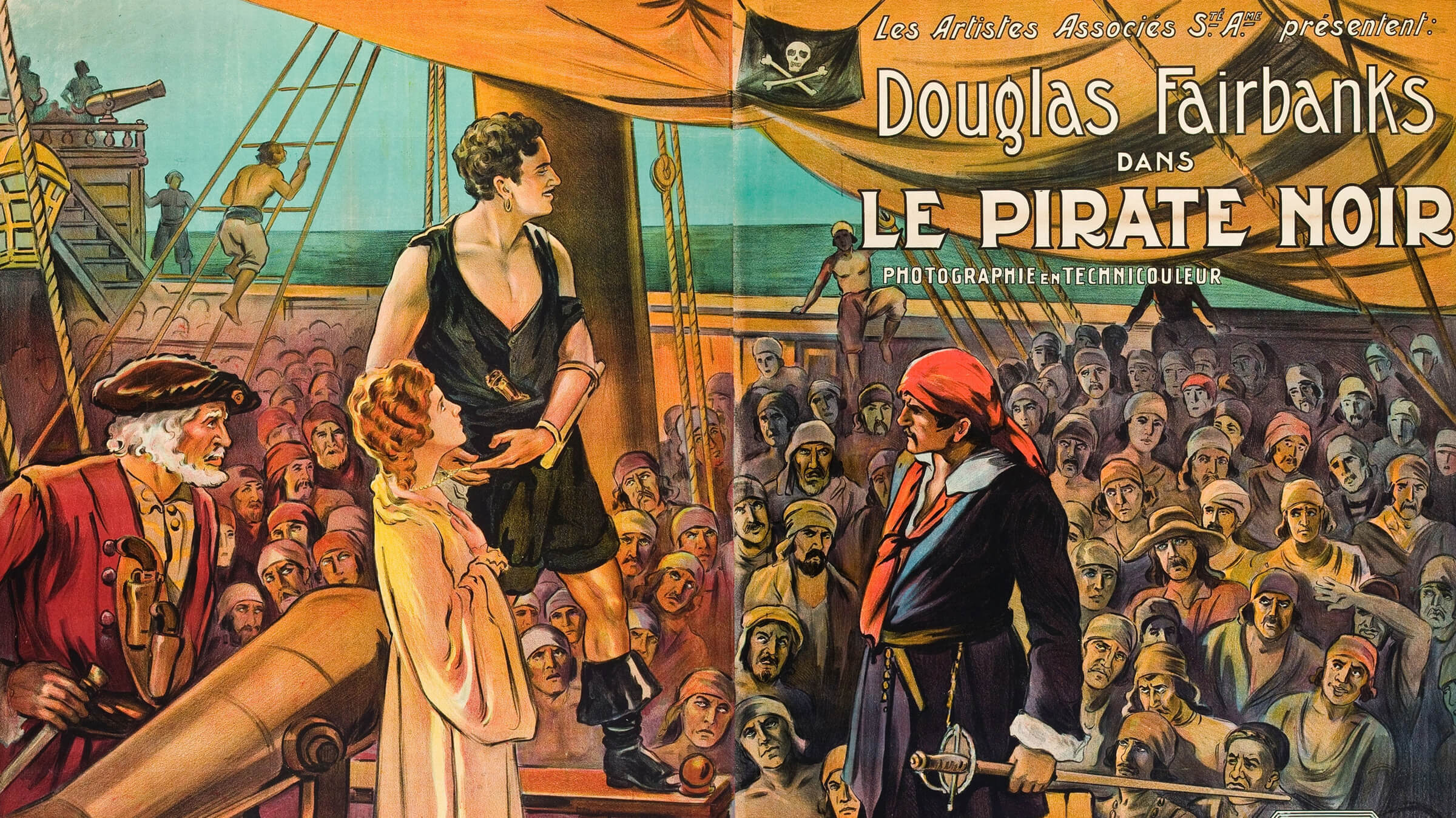

Because of Technicolor’s expense, the production had to keep the running time short and simplify the story line. Drawn from all the buccaneer stories Fairbanks had read in his youth, the script borrowed material from a scenario written in 1923 by Eugene W. Presbrey as well as ideas from Johnston McCulley’s “The Further Adventures of Zorro,” including the heroine being captured by pirates, the hero swinging through the rigging of a pirate ship, and a race to the rescue by the hero’s confederates in a pursuing vessel. It also has elements clearly influenced by Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and James M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. Fairbanks wanted the film’s visual design to be akin to the illustrated Book of Pirates by Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth’s illustrations for a 1911 edition of Treasure Island.

Fairbanks and his crew went to Santa Catalina Island for location tests but decided that they needed complete control, so nearly all the exteriors were filmed at the Pickford-Fairbanks Studios. They made several tests and discovered that the two-color process did not reproduce color accurately; blues registered as green and yellows as orange. Fairbanks disliked the bright hues and sought a more subdued approach. The film’s director, Albert Parker, later said that their aim had been to “take color out of color,” and that it was Fairbanks’s idea “to make a pirate picture that would seem to spectators as something that had been down in the cellars for 300 years, and looked as if it has been cleaned and varnished for theater showing.” By the time the testing phase was completed, more than fifty thousand feet of negative had been exposed.

The vagaries of the color cinematography required two sets of costumes and two sets of makeup because there was a disparity between how they photographed in natural light versus artificial light. Fairbanks himself is wonderfully clad in black to further distinguish him from the colorful cutthroats inhabiting the film. As a costume, it was one of his most inspired. Gene Kelly—whose childhood idol was Fairbanks—virtually replicated the costume for the magnificent “Pirate Ballet” sequence in Vincente Minnelli’s The Pirate (1948).

Principal photography for The Black Pirate was accomplished in nine weeks, five of which were spent on exteriors. The production successfully integrated brilliant miniature ships with the full-scale ships. A huge tank, reportedly holding seventy thousand gallons of water, was constructed, with airplane propellers creating the waves. Sections of the Pickford-Fairbanks Studios back lot looked like a shipyard, with five “fighting sets,” complete with sections of seventeenth-century galleons built under the supervision of the art director, Swedish-born painter Carl Oscar Borg. The climactic rescue sequence was filmed off Santa Catalina Island and also incorporated long shots involving miniature ships.

The most celebrated sequence of the film, and perhaps of Fairbanks’s entire career, is the moment in which the Black Pirate slashes a line with his knife, catches the end of the mizzen, and swings upward with the wayward sail to the main topsail. He then plunges his knife into the (pre-sliced) canvas of the topsail and slides down the sail, supported by the hilt of his knife as it severs the canvas in half. He rends the mainsail in the same manner. Airplane propellers behind the canvas provided the billowing effect for the sails. The feat is so spectacular that Fairbanks repeats it once more with the fore-topsail. Wearing a wire harness, with his arms and legs taped to prevent friction burns, the forty-three-year-old showman is in top physical form, and the appearance of effortlessness, the breathtaking arcs of movements, and the sheer joy with which he accomplishes the impossible are ample demonstrations of Fairbanks’s kinetic genius.

Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times described the film’s U.S. premiere in March 1926 in New York City: “The audience was ushered into the realm of piracy by the singing of ‘Fifteen Men on a Dead Man’s Chest’ and afterward by a ghost-like voice that asked everyone to go back to the days of bloodthirsty sea robbers. With its excellent titles and wondrous colored scenes this picture seems to have a Barriesque motif that has been aged in Stevensonian wood.” Photoplay reported, “Nothing has ever been done in colors on the screen that approaches it in beauty and uniformity … Mr. Fairbanks, for the first time in motion pictures, has secured the beautiful effect of mural paintings.”

Fairbanks never attempted a feature-length Technicolor film again, although he filmed a Technicolor sequence for his next film, Douglas Fairbanks as the Gaucho (1927). Color was expensive (exhibition prints for The Black Pirate cost a staggering $170,122.14) and in itself not a sufficient draw at the box office, but Fairbanks may have sold the exhibitor rights too cheaply. United Artists chief Joseph M. Schenck recalled a dazed Fairbanks handing him a letter from an exhibitor who had enclosed a check explaining that he had made such an enormous profit on a one-week engagement of the film that his conscience troubled him. The Black Pirate ultimately grossed $1.8 million domestically.

For many years, the film was available only in black-and-white versions. Just a portion of the cut original camera negative survived, and all the original Technicolor prints had faded. Nevertheless, at Douglas Fairbanks Jr.’s urging, the British Film Institute National Archive reconstructed the picture in the early 1970s with Technicolor providing new separation masters in its long obsolete two-color process. Film historian Rudy Behlmer noted that the project was an ambitious undertaking for 1970 when film restoration—let alone a full-scale 1926 two-color Technicolor reconstruction—was not the routine activity it is today.

The Black Pirate remains a landmark achievement in the advancement of cinema as an art form and the definitive pirate film of the silent era. The film is also a wonderful showcase for Fairbanks as a leader in the film industry and one of the most creative producers Hollywood has ever known.

Presented at A Day of Silents 2015 with live music by Alloy Orchestra