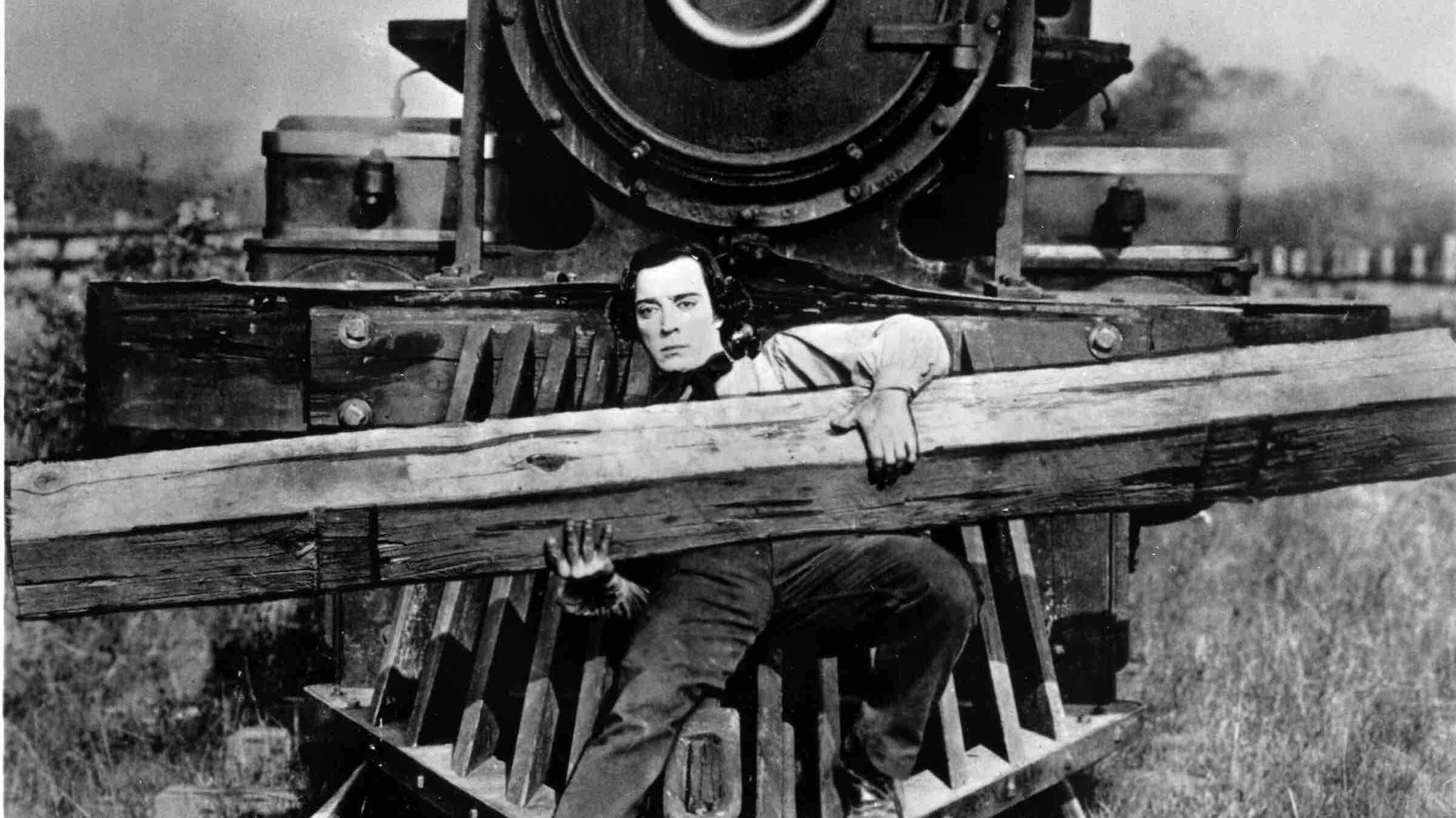

No silent moviemaker ever engaged with the machinery of modern life as resourcefully as Buster Keaton did. From One Week (1920), his debut as a solo director after his apprenticeship with Fatty Arbuckle, to The Cameraman (1928), his final masterpiece, Keaton routinely sparred with the mechanized world. He could be confounded in his early shorts—sometimes modern conveniences got the best of him—but as Keaton moved into feature films and matured as a filmmaker, his characters persevered in the struggle, thanks to a combination of curiosity, commitment, and ingenuity. Whereas Chaplin waged war against the machines with underdog defiance, Keaton mastered the magnificent marvels of modern engineering to triumph over seemingly insurmountable odds. In The Navigator (1924), Keaton tamed an abandoned luxury liner and emerged with one of the biggest hits of his career. After making three features of a more modest scope, The General (1926) marked his return to filmmaking on an ambitious scale. Built around a majestic prop that becomes a character in its own right—a locomotive steam engine—it is still filled with intimate moments. It is a grand achievement.

The story of The General comes from a chapter of Civil War history, a true tale of Union spies who infiltrated the South, stole a passenger train in Georgia, and drove it north pursued by Southern conductors who eventually captured the raiders. According to Keaton, Clyde Bruckman, his reliable collaborator and gag man, handed him William A. Pittenger’s account of the incident as a potential project. Keaton streamlined the story to a deceptively simple structure of two mirrored chases—one north to recapture the stolen engine and another back south—as well as added a love interest and a kidnapping to make the rescue personal. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, he took on the perspective of the South. Pittenger was a Union soldier who participated in the operation, and his book describes an ambitious failure that ended with the Union heroes captured and hanged. In Keaton’s version, the underdog Southern railroad engineer Johnnie Gray is the hero and the story ends with the Confederates triumphant.

Keaton wanted to shoot the film on location in Georgia putting into action the original engine, which was preserved and on display at a railroad station in Chattanooga, Tennessee. The owners (understandably) refused permission. Keaton also discovered that the Southern locations had changed too much to represent Civil War-era Georgia, so set designer Fred Gabourie found the perfect stand-in: Cottage Grove, Oregon, a small town in Willamette Valley with railroad tracks left over from the lumber boom. Keaton hauled two vintage engines, remodeled railroad cars, Civil War artillery, more than one thousand costumes, and all the equipment needed to shoot a film and settled in Cottage Grove with his crew to shoot over the summer of 1926. Locals were recruited as extras and 500 members from the Oregon National Guard were outfitted in Confederate gray or Union blue for the battle scenes.

The General is admirably faithful to authenticity in costumes and props—the imagery evokes Matthew Brady’s Civil War photography—and its visual scope is not simply impressive, it is also dramatic and, at times, awe-inspiring. Keaton’s Johnnie Gray fights the Northern army practically single-handedly and Keaton the director frames it as a David and Goliath battle aboard charging locomotives, with Johnnie as a one-man crew scrambling over the engine. Leave it to Keaton to turn a “cast of thousands” moment of an advancing army into a background gag while the oblivious Johnnie toils away chopping firewood for the engine. The sheer scale of the scene gives what could have been a tossed-off gag and rudimentary piece of exposition a powerful sense of place and threat.

Keaton had delighted in the comic possibilities of a locomotive in miniature in his 1923 feature Our Hospitality, another period piece set in the South, this one built around a Hatfield and McCoy-style feud. For The General, he had the real thing, not a lampoon of a rural railway puttering cartoon-like through a comic strip of the rural South, but a full-size engine on a working track. (In interviews, Keaton maintained that Civil War trains were narrow-gauge and that the Cottage Grove lumber railway tracks were chosen in part because they were also narrow-gauge; silent film historian Kevin Brownlow points out that neither is correct and suggests that Keaton may have confused The General with Our Hospitality.) Keaton learned to drive the engine himself and before long, according to the publicity of the time, he could stop the train on a dime.

Responding in 1960 to an interviewer who called Keaton’s character in The General “a schlemiel,” Keaton countered, “In The General, I’m an engineer.” It’s a simple statement of fact that speaks volumes about Keaton the filmmaker. He plots the comic geometry and action sequences in line with the design of the tracks and the landscape with exacting precision. There are no miniatures or rear-projection backdrops here. Every scene plays out on real engines charging past Cottage Grove’s actual forests and hills, and the sequences depend on the intricate planning of a mechanical engineer—for instance, a snub-nose cannon that threatens to blow Johnnie and his engine away until a fortuitous bend in the track provides a more opportune target.

For the scene in which Johnnie sets fire to a bridge to prevent the North’s engine from crossing the river, Keaton had Gabourie construct a stunt trestle designed to collapse under the train’s weight. It was the only sequence that did not use existing track and it has been called the most expensive single shot in silent film history (Keaton biographies put the cost at $42,000). It is certainly the most expensive that Keaton ever executed. He had only one shot at the scene and ran six cameras to capture the spectacle. The engine that plunged into the river was one of the doubles used to stand in for the working engines and it rested there in the water, rusting away for 15 years until it was hauled out for salvage in the scrap drives of World War II.

Keaton counted The General among his favorite films and it has since been hailed a masterpiece. But, in 1926, it was not so well received. It faced harsh reviews and slow attendance, and thanks to a budget larger than any previous Keaton feature, it lost money. It took decades for its reputation to rise from failure to classic. In 2012, it was ranked 35th in Sight and Sound’s “Greatest Films of All Time” poll, and it placed in the magazine’s top ten in 1972 and 1982.

Two historic finds relating to The General recently surfaced: a treasure trove of photographs and nitrate negatives taken by a local Cottage Grove photographer during the production of the film, and a copy of the original script that belonged to co-screenwriter Clyde Bruckman. Both were acquired by the Buster Keaton Society, which will present the material to the public for the first time at its 2014 Convention in October. Together, these finds will enrich our knowledge of the production of The General and perhaps offer more insight to the working methods of Keaton. The Buster Keaton Society has plans to publish a book showcasing the discoveries, but, as of this screening, the secrets of these invaluable documents remain a tantalizing promise.

Presented at Silent Autumn 2014 with live music by Alloy Orchestra