“I was getting sick of failure,” recalled Yasujiro Ozu of his early career, “and decided to make a film in a nonchalant mood.” The result was the Depression-era comedy Tokyo Chorus (1931), already the young Japanese director’s 22nd film and the one that marks the beginning of his “mature style.” “From this point on,” observes film historian David Bordwell, “Ozu is a major director.”

Having debuted as a director in 1927, Ozu had already churned out 21 films for the Shochiku studio by 1931, or about five a year, with some filmed in less than a week. (According to Ozu—a noted liquor aficionado—and his frequent collaborator and drinking buddy, the screenwriter Kogo Noda, each also took about “one hundred bottles of sake” to finish). Surprisingly for the man who later became the observational, patient dramatist of Tokyo Story and Late Spring, the majority were modern slapstick comedies, created under the influence of Ozu’s first mentor, the veteran director Tadamoto Okubo, who specialized in successful nonsense-monu for Shochiku. These “nonsense comedies” were barely coherent narratives loosely held together by an assortment of Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd-inspired sight gags.

By 1930, however, a new house style began to emerge from Shochiku and its main Tokyo site in the Kamata district. As the only film production studio left in Tokyo after the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923, Shochiku Kamata became the center for films addressing modern Japanese life, and the changes it brought: mass urbanization, rapid industrialization, and the rise of a new generation of middle-class office workers. A new genre blossomed, led by filmmakers like Yasujiro Shimazu, Heinosuke Gosha, and Hiroshi Shimizu: shoshimin-eiga or shomin-geki, “working-class” or “common-class” dramas, born to reflect the new lives and worried dreams of the suddenly urbanized, increasingly harried citizenry that were not only Shochiku Kamata’s target audience, but its neighbors as well.

Requiring no elaborate sets or costumes (a must, considering Kamata, like most studios of the time, had only one filming stage), this new genre of modern troubles was a perfect fit for Shochiku Kamata’s forward-thinking chief. Shiro Kido had already tapped into the power of modern Hollywood-like tools of commercial promotion (with his own print publication, Kamata, crowing the virtues of his various heroes and heroines) and mass media (drawing many stories from already popular, serialized newspaper stories and novels). He also had a soft spot for the rising talent Yasujiro Ozu, and, after an early attempt at the genre (1929’s appropriately titled The Life of an Office Worker), Ozu rewarded Kido with the ground-breaking Tokyo Chorus, which begins with a foot firmly in the slapstick realms of pratfall-driven student comedies then morphs into one of the defining creations of not only the working-class genre, but of all silent Japanese cinema. Long before his 1950s masterpieces, Yasujiro Ozu became “Yasujiro Ozu” with this film while remaining—like all those in their late 20s—a bit rowdy at heart.

“Ozu tried to show his characters conversing in a serene manner, nodding gently as they talk,” notes the respected Japanese critic Tadao Sato on one of Ozu’s most characteristic aesthetic choices, but Tokyo Chorus bristles with both the chaos of his nonsense-monu origins and the class malaise of the time. Gentility and serenity are as impossible to achieve as a clean home, a happy work space, or dutiful children. Conversations quickly degenerate from orderly requests into slap-happy fan showdowns between workers and bosses, or impolite shrugs between teachers and students. In later Ozu films, fathers and their children speak politely and with a becalmed physical stillness (even if their words mask devastating emotions). However, here, in Tokyo Chorus, constant physical and psychological battles between fathers and sons disrupt the home; no matter who wins, it’s the adult who will always lose. (Any parent will recognize the hero’s hangdog post-argument expression. It’s a foolish thing to find yourself engaged in a battle of wits with a four-year-old, and even more tragic to lose it).

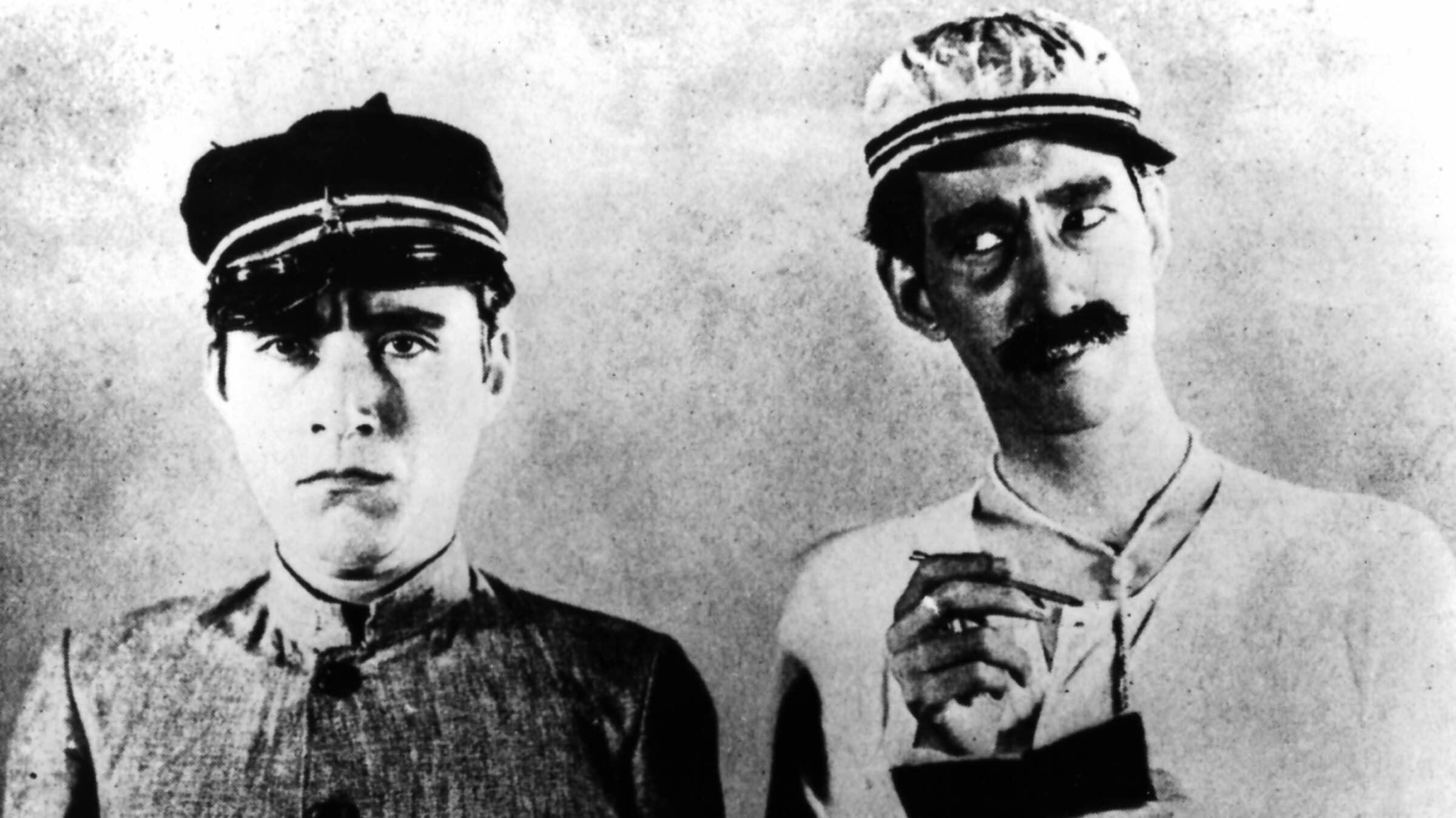

Serene walks along sea walls or city streets mark later Ozu, yet here the streets are filled with homeless scrounging for cigarettes, or individuals desperately pacing up and down the same block, sweating and brow-beaten, handing out restaurant ads to disinterested locals. Here, neat rows of students overseen by a spectacularly mustachioed teacher are broken by the mocking Chaplinesque stagger of a late-arriving student, and every row threatens to break down into chaos. It’s Ozu with the modern world’s troubles, especially Depression-era troubles, still highly visible (“Hoover’s policies haven’t helped us yet,” notes one character).

As different in action, tenor, and movement as Tokyo Chorus is from his later works, the Ozu that matured into “Ozu” emerges. “To elicit a performance from the form of movement without explaining how the character feels has always been Ozu’s approach as a director,” recalled the actor (and Ozu regular) Chishu Ryu. Here, a simple game of hand-clapping moves from a mother’s realization of her family’s plight to a shared glance with her husband to, finally, something far more powerful. A hand slowly fans a sickly child, followed by a young son, now no longer selfish, continuing the action. Ozu’s famous “pillow shots,” scenes of everyday objects and the landscapes around the characters and their actions, also appear. Clocks, trees, the tops of buildings, desks, food. A student’s view of trees blowing softly against a sunlit sky cuts into an industrial skyline spitting out smoke—that same student’s view, now that he’s joined the adult workforce. And, of course, Ozu’s devastating echoes and repetitions, his circular return to earlier moments, frames, and images that are almost the same yet have changed because of something missing, or something learned. Tokyo Chorus offers many similar touches, but none more so than the student groups that open and close the film. In one, the giddiness and disorder of youth is on full display; in another, the uncertainty of adulthood has seeped in, and, with it, all the doubt over the meaning of life’s chorus.

Tokyo Chorus earned Ozu third position on Kinema Jumpo’s list of Best Films of 1931; a year later, he finally won the top spot with I Was Born, But…. Ozu continued making silent films until 1936, loyally waiting until his director of photography Hideo Mohara finished perfecting his own sound-camera design. He went on to collaborate with Kogo Noda, the scriptwriter for Tokyo Chorus, through much of his career and continued to drink with him throughout each process. Shiro Kido stayed at Shochiku for a half century, although Shochiku Kamata closed in 1936, putting an end to “Kamata flavor.” Tokihiko Okada, the hero of Tokyo Chorus and a frequent silent-Ozu actor, died three years after filming from tuberculosis; his daughter at the time, Mariko Okada, one year old a the time, later starred in Ozu’s Late Autumn and An Autumn Afternoon. And the child actor that plays Miyoko, the family’s little daughter whose sweet tooth endangers her life? None other than Hideko Takamine, who grew into one of the finest actors of her generation.

Presented at SFSFF 2013 with live music by Guenter Buchwald