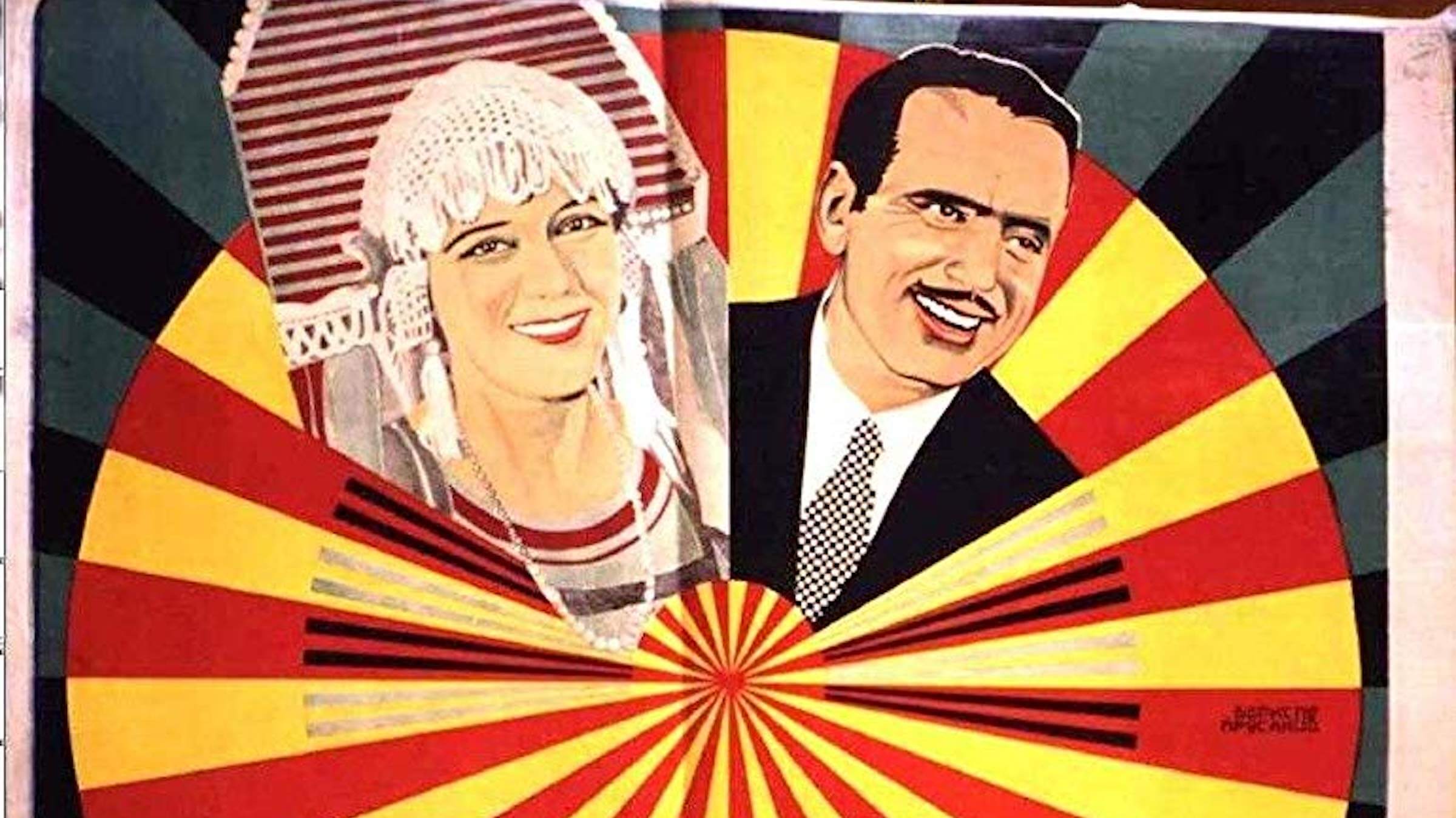

When Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks visited Moscow on a vacation trip in 1926, they were the most famous couple in the world. Among the first Hollywood celebrities, they were idolized everywhere, even in the Soviet Union, where audiences preferred American and German films to groundbreaking homemade fare like Battleship Potemkin, Mother, and Man with a Movie Camera. The couple’s visit to a Russian film studio provided Sergei Komarov, a member of the avant-garde movement, the chance to pay homage to American style comedies so beloved by Soviet audiences.

A Kiss from Mary Pickford was the first of only two pictures Komarov directed. A student of Lev Kuleshov, the father of Soviet montage, Komarov was a popular actor, appearing in 31 features, starting with the agit-prop Serp i molot (Sickle and Hammer, 1921) and ending with the science-fiction spy thriller Tayna dyukh okeanov (The Secret of the Two Oceans, 1955). In A Kiss from Mary Pickford, Komarov spoofs the unprecedented fame reached by American stars like Pickford and Fairbanks, the fickle nature of fandom, and the state of the Soviet film industry.

An uncredited starlet at Biograph studios, Pickford helped to create the modern star system, as audiences clamored to learn about “the girl with the curls.” A comedian and swashbuckler, Fairbanks was the reigning male sex symbol of the late ’teens and ’20s. Both were married to others when their relationship began in 1916. The hint of scandal surrounding them did nothing to diminish their popularity, and may even have enhanced it after they were finally free to marry each other in 1920. “America’s Sweetheart” and “Everybody’s Hero” were met in their travels by receptions usually reserved for royals. During their London honeymoon, the pair was mobbed by thousands of fans who pulled Pickford from a car. Both stars suffered bruises and scrapes as they fought to escape the frenzied crowd. Similar frenzy met them wherever they traveled, including the visit to Moscow where they stopped at the Mezhrapom-Rus film studios. While newsreel cameras rolled, Pickford embraced Russian actor Igor Ilyinsky in a typical photo-op. Komarov built an entire feature around this single shot, employing the montage techniques he had learned from Kuleshov.

By the time Komarov made A Kiss From Mary Pickford, the Soviet film industry had reached its apex. An economic crisis that started before the turn of the century—and which sparked the Communist revolution of 1917—made the production of movies extremely difficult. Revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin saw motion pictures as a way of extending Marxism to the nation’s mostly illiterate population and invested in its growth. Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) of 1921 relaxed state control of some industries, creating a mini-capitalist structure within the Communist economy. Privately-run movie theaters blossomed. Urban audiences, flush with cash after years of hardship, sought entertainment and found it in movies imported from the West. American and German films were the most popular, with the adventures of Harry Piel, considered the German Douglas Fairbanks, especially favored.

Kuleshov formed a cinema workshop in 1920. An admirer of the films of D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin, Kuleshov wrote, “We must seek the organization of cinematography not in the limitations of the exposed shot, but in the alternation of these shots.” The editing approach Kuleshov described as “American montage” was later called “Soviet montage” by critics and historians. Noticing that audiences preferred foreign movies to Soviet product, Kuleshov, in 1922, defined this phenomenon as “Americanitis.” “Deep-thinking officials get … frightened by ‘Americanitis’ … in the cinema and explain the success of the particular films by the extraordinary decadence and poor ‘tastes’ of the youth and the public of the third balcony.”

The earliest Soviet cinema was not so different in technique from the movies of the pre-revolutionary Russian Empire, which were dominated by exaggerated acting, melodramatic plots, costume dramas, and long, uninterrupted shots—much like early American films. Adapting the tools of Griffith and other American and European directors to the service of the Soviet revolution instead of commerce, Soviet filmmakers incorporated American-style parallel editing as a deliberate effort to transcend theatrical style.

Unfortunately, the homegrown films remained unpopular. In March 1925, 79 percent of movies on Soviet screens were made outside the country. The magazine Kino-Front published a letter in 1927: “I want to forget myself. I want romance. For that reason I love Harry (Piel), Doug (Fairbanks) and Conrad (Veidt).”

A Kiss from Mary Pickford attacks Americanitis with a nod and a wink. Acknowledging the appeal of American stars, Komarov’s film critiques the hysteria that accompanies popular phenomena, whether it’s the appearance of a celebrity, a rumor, or a revolution.

After Josef Stalin assumed dictatorial control of the Soviet Union, he suspended the NEP in 1929. Film production declined rapidly, from 148 feature films in 1928 to 35 in 1933. Imported films were also curtailed, and the film industry was purged of “counter-revolutionaries”. Among the targeted filmmakers were Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and Dziga Vertov. The new direction of Soviet cinema became the “struggle for the high-quality-art-mass film which satisfies the basic demands of the proletarian collective farm mass viewer,” according to a 1932 bulletin of the newly formed studio collective Soiuzkino.

The films and writings of Kuleshov, Eisenstein, Vertov, and V.I. Pudovkin had made their way to America and Europe, where they were circulated among academic and avant-garde communities. Eisenstein himself came to Hollywood in 1930 at the invitation of Paramount Pictures, where he adapted Theodore Dreiser’s novel An American Tragedy for the screen. The film was scuttled by David O. Selznick, who wrote that Eisenstein’s screenplay made him “so depressed I wanted to reach for the bourbon bottle.”

The popular films of the Soviet silent era were rarely, if ever exported, as there wasn’t enough positive print stock available to justify the expense. During the Cold War, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov were all the West knew of the legacy of Soviet cinema, because prints of these directors’ films remained in the collections of film clubs and cinémathèques. Their artistic innovation, combined with their vision of a pre-totalitarian Soviet idealism, made these films shining examples for a left-leaning academic elite in the West, which considered these films as typical of the Soviet silent era. Film historian Jay Leyda reintroduced the legacy of Soviet and Tsarist cinema to the West when he published Kino, a comprehensive history of Russian film, in 1960. Textbooks and histories continue to promote the idea that Soviet silent cinema was dominated by the avant-garde rather than fare like A Kiss from Mary Pickford.

Ironically, Fairbanks may have contributed to this misapprehension. A German Communist newspaper reported that he had said that Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin was “the most intense and profoundest experience of my life,” after seeing the film during the same trip that resulted in A Kiss from Mary Pickford.

This print of A Kiss From Mary Pickford comes from the Mary Pickford Institute. It was struck from a duplicate negative given to the Mary Pickford Company in the early 1970s by a Moscow film archive. Fairbanks died without knowing of the film’s existence. Pickford reportedly learned of the film in the late 1940s, but her reaction is unknown.

Presented at Special Event 2009 with live music by Philip Carli