When’s the last time you were surprised by a silent film? Impressed, dazzled, yes, but genuinely surprised? You’d think by 2017, with all the silent-era history scholarship behind us, that authentic, mutant-DNA “Holy Crap” moments would be rare on the ground, and, of course, they are. But there’s no amount of buckling up that can prepare a well-versed silent cinephile for the utter unheralded weirdness of Teinosuke Kinugasa’s A Page of Madness (Kurutta Ichipeiji). Scan the sacred texts, from Paul Rotha onward—it’s not there, as if it were a disturbing dream filmgoers may’ve thought they’d had, fleeting but creepy, after a big meal and too much wine.

Of course, the fact of it being an Asian silent—and not a silent made marketable by bearing the mega-auteur imprint of either Yasujiro Ozu or Kenji Mizoguchi—automatically means it passed little seen by Western audiences for decades, and thus fell out of the “official story” of cinema’s evolution. Even the annals of scholarship about avant-garde or experimental film, a legacy to which Kinugasa’s movie definitely belongs, rolled on for decades ignorant of its existence. Even in Japan it was largely unknown, a lost film, until the director discovered a copy in his own storage shed in 1971, years after he’d retired.

The historical anomalies don’t stop there. The film itself is a monster out of time, perhaps the most psychotic Japanese silent film ever made but also a piece of work that completely muddies how we thought film history happened, and when. The fact that Kinugasa was etching his fever-dream (with the help of an avant-garde theater company) at more or less the same exact time as the Surrealists and the Soviet mad scientists were creating theirs, and with little or no cross-pollination, scans something like evidence for a conspiracy theory. How did this freakazoid come to be? Decades later, Kinugasa admitted to seeing some American silents, singling out the work of Rupert Julian, of all people (like Kinugasa, Julian also worked as an actor), and, significantly, loving F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924), but that was as far as his influences are thought to have gone. Murnau’s film, we surmise, had a major impact, but even so, the frantic layering and electric montage of Kinugasa’s film feels sui generis, a film born accidentally, organically, out of its own primordial cinematic soup.

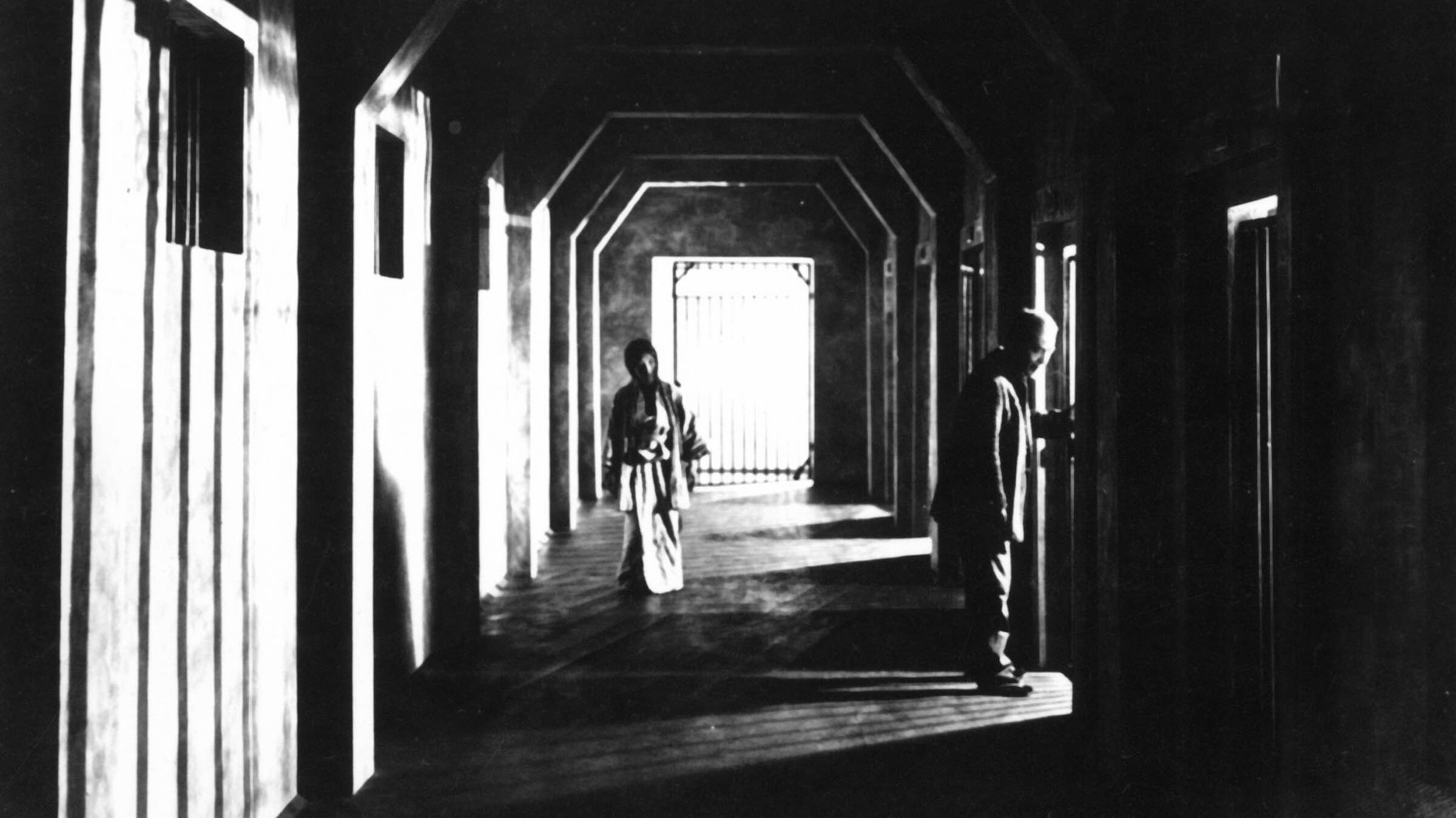

In Japan, it got nominally noticed. It was deemed so unique it was booked only in theaters specializing in foreign films, frequented by adventurous moviegoers, and led to Kinugasa (who had made thirty-four earlier films, all now lost) forming his own production company, getting distribution by Shochiku, and launching into a far more orthodox career lasting more than forty years and another eighty films, including Gate of Hell (1953), winner at both Cannes and the Oscars. Looking at Page’s unfettered modernist assault, Kinugasa’s evolution into one of the giants of mainstream Japanese cinema may seem inexplicable, but take another look—the mise-en-scène is so narratively clear, aided by flashbacks and nonstop subjectivity, that not a single intertitle card of exposition is needed. (In Japan it was accompanied, as almost all films were, by a benshi narrator, and the rare museum screenings of the last few decades have often included neo-benshi participants.) Set almost entirely in an insane asylum, the movie relates the tribulations of a beleaguered man (Masao Inoue) who works as a janitor in the institution where his insane wife (Yoshie Nakagawa) is a patient. How she became this way, and what guilt the man bears, is revealed in time (the fragmented backstory involves a storm, and the death of an infant), as he attempts to connect with her through the bars, and save her during a climactic riot of patients. His sanity begins to crumble, too, after his daughter (Ayako Iijima) visits with news of an impending wedding. As the perspectives begin to twist, the matter of who belongs on which side of a locked cell door becomes frighteningly unclear.

It’s the film’s unforgettable visual intensity that leaves a footprint in your memory. It begins with a vision out of the madwoman’s fantasy life: a dancing princess in front of a vast, spinning ball carpeted with striped fur—what?—and from there, Kinugasa brings a murderously inventive battery of ideas to bear, using double and triple and sometimes quadruple exposures to disorient us. A guard will open a barred door, and the bars will remain; a nervous tracking shot down the central hallway is layered atop a tracking shot going in the opposite direction. Memories are seen through the hazy windows of hallucinations, while in-the-moment experience is literally, visually, haunted by the past. In one disarming moment, during a walk on the institute grounds, the foreground characters are clear while others, just a few feet away, are whited-out, shot perhaps through a vast white veil, creating a vivid sense of ghostly dislocation.

You never know where the camera will go or when or why, or when the movie will erupt into a free-associative montage seizure. But it’s not random; most of the film is formally very rigorous, as in the tour-de-force memory sequence of the wife at various points in her life—socializing, laughing, brooding, raving—in a series of short shots connected by the motion blur of swiveling, circular pans. The imagery itself is never less than chilling and ghostly, with the inmates’ hyperspeed manic dancing (and creepy use of Japanese girls’ long filthy black hair, presaging the J-horror trope of the last twenty years), the foggy and insinuating sense of psychotic danger, and the climactic freakout, in which, post-riot, the janitor doles out homogenous, smiling Noh masks to the lunatics, including his wife and himself, calming everyone and creating a spontaneous tableau of placid happiness, in lieu of an actual resolution to everyone’s torment. For the Japanese, the masks signify a traditional mode of High Culture, a familiar if ironic flourish in this hothouse avant-gardism. For most of the rest of us, the effect is still fantastically spooky, the masks seeming to further dehumanize the characters, robbing them of identity and will.

As Nipponophile-scholar Donald Richie has pointed out, expressionism per se has always been welcome and understood in Japanese culture, where realism and naturalism were secondary to stylized and anti-naturalistic representation. The German Expressionism of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), so radical a step in every other cinema culture’s evolution, was simpatico for Japanese audiences, and catnip for Kinugasa’s clique of avant-garde artists (which included Page scenarist and eventual Nobel-winning novelist Yasunari Kawabata). But in terms of disjunctive flow and pacing alone, it remains that Kinugasa’s film was an alarming departure from the simple visual syntax of Japanese silent films, and it doesn’t resemble the Germans very much either.

Ultimately, it may be the best—that is, the most fascinating and the most terrifying—madhouse movie ever made and makes all other efforts at visualizing the subjective experience of mental and emotional disarray look childish and campy by comparison. Looking at the film’s evocative textures, it’s difficult not to align it as an influence or a prophecy on or of everything from Carl Dreyer to Picabia to Samuel Fuller’s Shock Corridor, despite going almost entirely unseen in the West. (One might feel compelled to claim an exception to that idea: Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon, shot in 1943, feels so haunted by Kinugasa’s film that you could be convinced that Deren had seen it in her 1930s avant-garde circles, somehow, and seen in it a way to express the ineffable on film.)

The feeling of A Page of Madness is of being exposed to a secret cinema, a covert subconsciousness-caught-in-amber history of movies, happening beneath the culture we thought we knew, perhaps while we sleep. There are, thank God, still mysteries to unearth in the forgotten closets of the world, and still unknown movie experiences that seem to have come out of nowhere.

Presented at SFSFF 2017 with live music by Alloy Orchestra