Published in conjunction with the screening of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at SFSFF 2023

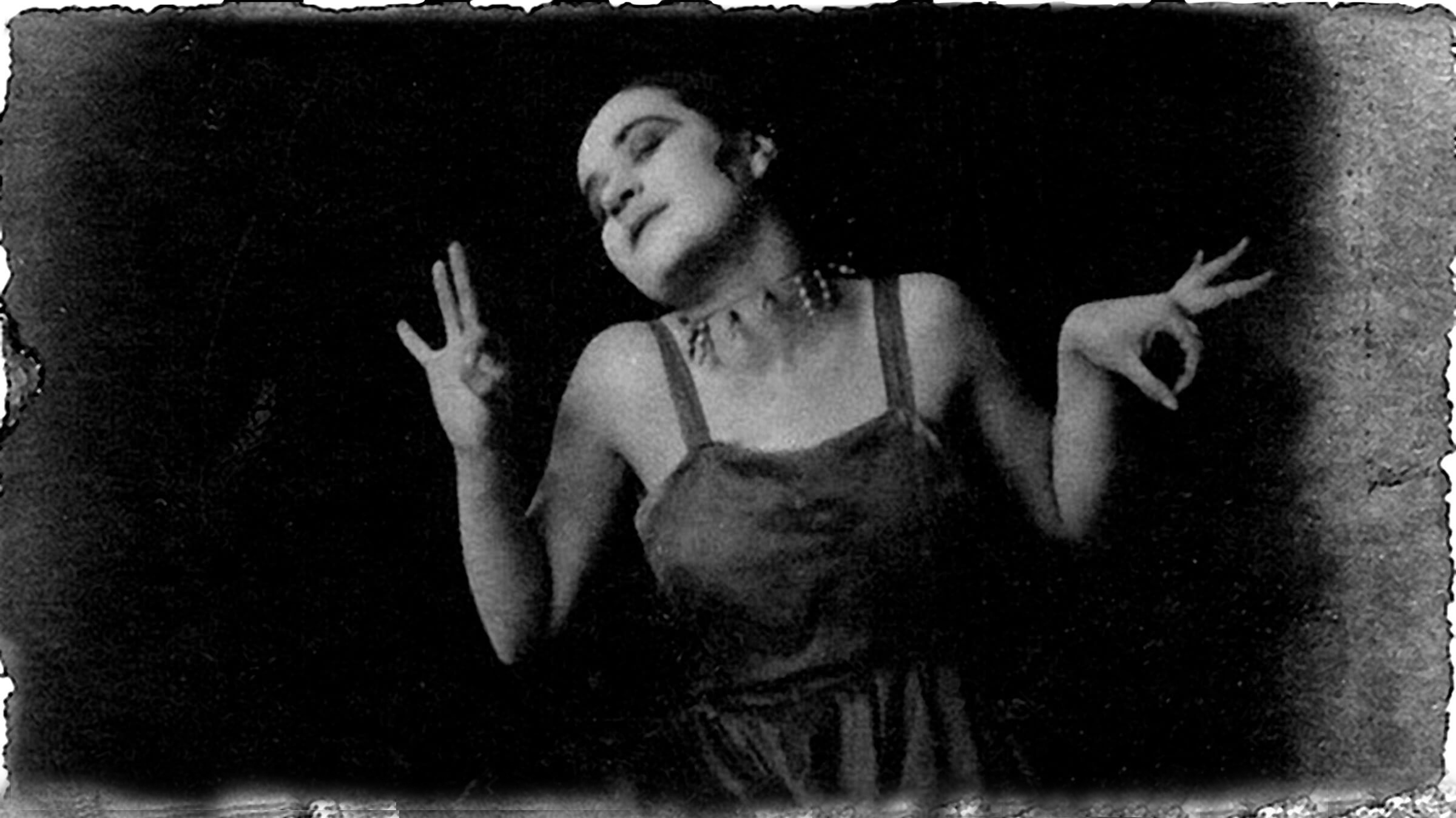

As the projectionist changed reels, Valeska Gert held completely still, her arms raised. Through her Weimar-era piece “Pause,” the Berlin-born dancer associated her body with the material basis of film. Gert also put her edgy and compelling performance style on film. Her physicality pushed the limits of a 2-D medium, conjuring smells, sounds, and tactile sensations. Critic Oswell Blakeston described the impact of Gert’s lone close-up in A Daughter of Destiny: “The back number of a French illustrated paper fallen on the worn plush sofa at a cheap barber; the cartoon smudged with the dirt of anxious fingers. The face of that cartoon, with the smudges, come to life!” Gert’s contribution to Daughter of Destiny has been lost, apart from a still, but her talent for creating characters through movement spawned a series of silent-era grotesques that have survived.

Punk Nightmare: A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1925)

Jerking around like a rebellious punk rocker, Gert revels in Puck’s unsettling weirdness with her bulging grimaces, twitchy blinking, and flicking tongue. The image of Puck squatting above Titania echoes The Nightmare, Henry Fuseli’s 1781 painting of an incubus planted atop a sleeping woman, except Puck’s legs are splayed like she’s about to relieve herself. Gert’s wanderer of the night seems to reek of the untamed woodlands: dampness, decay, and the scent markings of wild beasts. Her performance also evokes the mechanical. While Puck administers the confusion drug to a sleeping mortal, her arms snap from position to position as if controlled by gears. Behind the scenes, a hostile director stoked Gert’s anxiety. Furious that Gert refused to cut her hair, Hans Neumann lashed out at the dancer and blamed her fatigue on promiscuity. In fact, as she later wrote, “I was tired because the fear of shooting prevented me from sleeping. I never wanted to start making movies again.”

Flesh Peddler: The Joyless Street (1925)

Fortunately, photographer Suse Byk helped Gert shed her discomfort with being filmed. By the time Gert embarked on her first collaboration with G.W. Pabst, she was able to take “pleasure in what had pained me before: being captured by the camera … And the camera multiplied the audience by millions. Fantastic!” Gert’s newfound ease on screen resulted in her bawdy, complex characterization of Joyless Street’s Frau Greifer. Against the misery of the meat queue, Greifer’s laughter is almost audible as her head turns every which way like a bird’s. Gert’s charisma pulls focus away from the languishing loveliness of Greta Garbo and onto her unappealing procuress. Tempting Greta’s Rumford with luxury, Greifer’s smirking face rolls along the edge of a fur coat, giving viewers the sensation of caressing its softness. When Greta freezes at an arranged assignation, Greifer’s awkward stare before offering herself up as a replacement, wrings rancid humor from the situation.

Dialectic Domestique: Nana (1926)

In the frame of a long mirror, Nana and Zoe present a striking contrast: the bouffant-topped courtesan in a lacy robe versus the plain chambermaid in a long gray dress, crouching nearby like a pet. Gert crafts some of Nana’s sharpest comic moments and conveys Zoe’s waxing insolence. When the weak-willed Georges squirms over his uncle’s confrontation with Nana, Zoe pauses disdainfully with downcast eyes and fires off a wry gesture of dismissal, three slicing waves over crossed arms. Then later, as Nana reduces Count Muffat to a begging pooch, Zoe can hardly pry herself away. With each sideways step through the door, she keeps her eyes trained on the spectacle of an aristocrat’s abasement. When we last see Zoe, she’s draped in Nana’s cape as she mocks Muffat in the street. Her snide restraint has given way to open shrewishness, like a guignol imitation of Nana’s hauteur.

Leering Disciplinarian: Diary of a Lost Girl (1929)

Of the working relationship between Pabst and Gert, Louise Brooks recalled, “he adored her.” Gert’s exploration of the sordid, the taboo, and the perverse overlapped with the preoccupations that drive some of Pabst’s greatest silents. As Sydney Jane Norton notes, Gert’s performance art satirized bourgeois moral failings. In Diary of a Lost Girl, Gert skewers hypocrisy by endowing the reformatory director, a human metronome of sadism, with riveting ugliness. An oversized crucifix hanging around her neck, she combines the severity of a nun with the lecherous arrogance of a tyrant surveying his concubines. Gert owns arguably the most memorable scene of the film. As she beats the gong in accelerating rhythm, the girls bend and reach, bend and reach for their nighttime exercises. Her face contorts with growing arousal then erupts as the screen fades to black.

The Other Woman: Such Is Life (1930)

Through dance, Gert portrayed what she described as, “the people that the upright citizen despised: whores, pimps, depraved souls—the ones who slipped through the cracks.” That spirit of defiance and solidarity with the marginalized pulses through her vital performance in the Czech film Such Is Life. Gert’s barmaid cavorts with a washerwoman’s unemployed husband as he spirals into alcoholism. Instead of a hissable villainess, however, she emerges as a good-time girl whose alley-cat allure brings merriment to the bleak lives of working-class men. Her eyes shining over a beer tankard, she winks and pokes her tongue saucily into the corner of her mouth, flirting with a customer. Her riotous tabletop jig, supercharged by montage, adds a jolt of infectious excitement to the grim social drama. When news arrives that the washerwoman has been fatally injured, Gert flings herself face down onto the bed where she had been entertaining the laundress’s husband moments before. Flexing with the force of a sob, she exhibits a visceral compassion for another woman oppressed by the same harsh realities.