It’s yet another under-explored, under-restored arm of silent film history—Soviet Ukrainian cinema, at least the years before Oleksandr Dovzhenko began making his distinctly regional films in the late 1920s. Soviet film was, even into the 1980s, always unwittingly conflicted about its provincial cultures, torn between the official urge to homogenize them into uniform Communist art or to give in to celebrating the different ethnic identities—from Estonia to Kyrgyzstan to Yakutia—as a way to cultivate cooperation from far-flung groups with their own age-old traditions, priorities, and languages. The Ukrainians had their own state film monopoly—the VUFKU—that controlled all film production in the busy republic and operated with apparent independence from the larger Soviet bureaucracy. Scholars have noted that this initial distance from the Soviet hierarchy, which itself was in almost total disarray during the infrastructurally devastated postwar years (even Moscow didn’t have a single working theater until 1921), encouraged the Ukrainians to employ mostly pre-revolutionary-era talent. So, Ukraine’s film culture had, for a few years anyway, the distinctly sulfurous whiff of German Expressionism about it.

Little by little the urgent-realism Soviet style we recognize from Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov (who later made his films at VUFKU) crept in. The admixture of the two is what’s embodied in Heorhii Tasin’s Arrest Warrant (Order na Aresht), a little-remembered psychological potboiler that manages to pamper revolutionary temperaments just as it stretches beyond Marxist-Leninism to both subvert narrative convention and consider the impossible position of womanhood in a militarized culture that, however ostensibly gender-neutral, remained crushingly patriarchal. It does all this in a freeform narrative tumult that favors subjectivity over clarified what’s-what storytelling, employing tropes and techniques that seem, at least to modern eyes, to have been distinctly un-Soviet.

Talk about in medias res: Tasin’s film may well have been clearer to Ukrainian audiences in 1926 than to us today, beginning as it does in a revolutionary municipal office mobilizing in a panic, apropos of who knows what—clearing out, we end up assuming, before the White Army gets there, which places the unmentioned year as 1918, when the Red vs. White Civil War was still raging tit-for-tat in Ukraine. In the fracas we meet Nadia (Vira Varetska), the devoted wife of studly Committee Chairman Serhii (Khairi Emir-Zade), who entrusts her with an envelope she must guard with her life. Listening and watching nearby is the shifty Valerii (Nikolai Kutuzov), whose sly demeanor immediately signals to us that there’s a fly in the comradely ointment. The two men end up on the same wagon out of town, sharing a smoke; only we know something counterrevolutionary is afoot. But wait, did one of them jump off and run back into town?

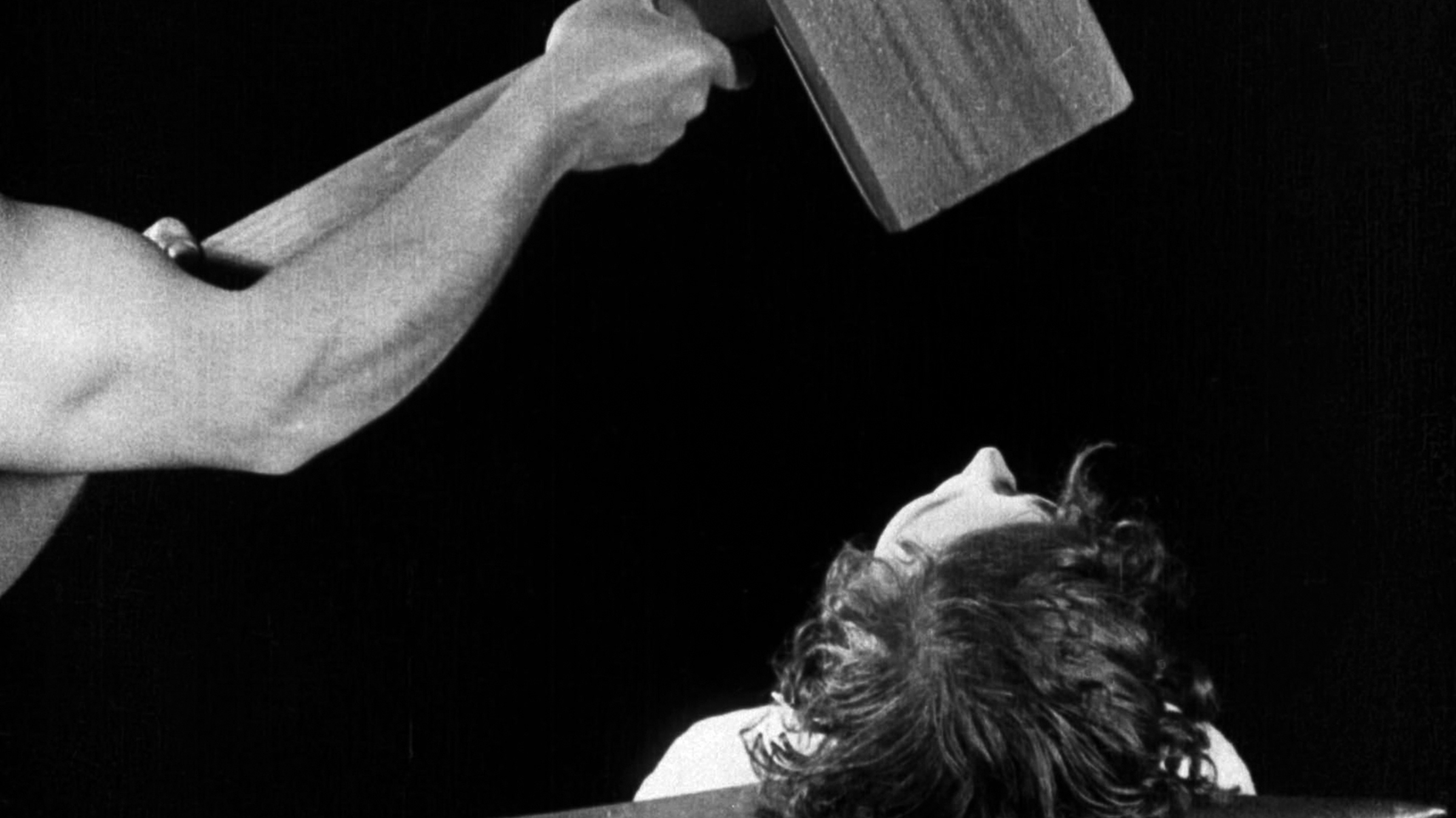

As the Whites march in, Nadia hides the envelope in a hole under brush and dumps all evidence of her husband in a pond. She and her young son are still treated to a thorough ransacking, and she is eventually arrested. Thus begins the film’s meaty Act 2, in which the White intelligence officers try everything they can think of to break her down and divulge the location of the “package” they know she has. Fate is not on her side—eventually, her son’s peppy dog provides the giveaway moment to prying eyes. For Nadia the interrogation is by turns subtle and brutal, sapping her will and crippling her sanity and if the early parts of the film, in their shadowy visuals and blocking, remind you far more of Fritz Lang’s spy films than classic Soviet agitprop, the heart of the movie evokes lurid Germanicisms like Robert Reinert’s Nerven (1919), Robert Wiene’s The Hands of Orlac (1924), and two by F.W. Murnau, Phantom (1922) and The Last Laugh (1924)—not to mention G.W. Pabst’s Secrets of a Soul, made the same year as Tasin’s movie. (As vexing as it might’ve been in the 1920s, Tasin was an ardent Germanophile and he was also head of the Odessa Film Studio and went on to adapt Upton Sinclair’s socialist antiwar novel Jimmie Higgins, one of his greatest successes.) Nadia’s deteriorating consciousness is conjured in a shotgun blast of montages, packed with dream imagery, fragmented memories, subliminal cuts, Pudovkinian associative edits, double exposures, careening handheld camera stumbles, even cutaways to a cat hunting and catching a mouse. Spider webs, fire, crashing ocean waves, vertigo abstractions, face-reflection distortions á la Murnau, hallucinations of her child visiting her bedside as though he were a ghost—Tasin pours on the shattered subjectivity, being as overtly Freudian as any Soviet filmmaker of the era. It verges on a German horror film. Tasin may today be most famous for scripting Vladimir Gardin’s 1923 Poe-riff A Spectre Haunts Europe—but as the empathic bond with the heroine’s plight in Arrest Warrant is always prioritized, Tasin’s film looks forward a few years to Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, the era’s definitive take on women’s experience of systematic oppression.

In its final act, Arrest Warrant, as Valerii and Serhii both emerge from the shadows, turns some serious narrative tables, actually deepening and complicating each characters’ motivations and ethical conundrums in ways mainstream Soviet films weren’t allowed to do just a few years on. In terms of its proto-feminist focus, and the angsty romantic triangle that manifests (with a child at its centroid), the movie may well have been a precedent for Abram Room’s controversial and groundbreaking Bed and Sofa in 1927, suggesting to us that Soviet silents, in a broad way, were more open to human complexity and contradictions to Party propaganda than we ordinarily surmise from the predominance of the established film school classics.

But perhaps even more so in Ukraine. Tasin’s film explicitly critiques the prescribed Party thrust, building a narrative in which even all the devoutly Red characters are beleaguered, compromised, and in the end condemned to personal and revolutionary failure. Soviet films were often tragic, favoring martyrdom against tsarist or, later, Nazi, combatants, but Tasin’s climax seethes with a tragedy carrying no revolutionary takeaway. It’s as though war, and revolutionary struggle itself, is being envisioned as a lose-lose dynamic.

It’s not hard to sniff out here the bitterness left in the contrails of the Ukrainian-Soviet War, which raged on the ground amid battling revolutionary factions (not just against the Whites) from 1917 to 1921 and must’ve left a lingering sense of ambivalence in Ukraine about the practical coherency of the Soviet experiment. With that in mind, Tasin’s film can feel almost revelatory—a glimpse of a granular historical gray area into which we, as Westerners, have had precious little insight. Fittingly for a film centered on a woman’s plight in a roiling man’s world, everything is contingent on power, and the only certainty is betrayal.

Presented at SFSFF 2022 with live musical accompaniment by the Sascha Jacobsen Quintet