EMAK-BAKIA

Directed by Man Ray, France, 1926 | Print Source Cohen Film Collection

Live Musical Accompaniment by Earplay from an Original Score by Nicolas Tzortzis

MÉNILMONTANT

Directed by Dimitri Kirsanoff, France, 1926 | Print Source Cinémathèque française

Live Musical Accompaniment by Stephen Horne

In 1921 when Dimitri Kirsanoff was shooting his first film in Paris and Man Ray had just arrived there, the city wasthere, the city was the site of an aesthetic revolution. Artists were discarding painting in favor of assemblages and “readymades” like Duchamps’s famous urinal. Surrealists swapped narrative fiction for experiments in automatic writing. The composers of Les Six rejected Wagner for Gershwin. It was a heady atmosphere for the émigré artists then flooding Paris, whether leaving behind the turmoil of eastern Europe like Kirsanoff or the conservatism of middle-class America like Man Ray. The world that had produced the devastating Great War clearly needed drastic revision, and the avant-garde artists were up to the task.

The newest of these new art forms was avant-garde film. “An unforeseen art has come into being,” wrote Jean Epstein in 1921. “We must understand what it means.” In fact, avant-garde films were then defined less by their aesthetics than by their precarious position on the margins of commercial cinema. As they struggled to gain recognition, avant-garde filmmakers and their allies inadvertently fueled the explosive growth of a film culture we take for granted today: film coverage in daily newspapers, film magazines, cinema clubs, lecture series, museum exhibitions, repertory screenings, and art house cinemas. Today’s Castro audiences are the descendants of the cinephiles who pored over Ciné pour tous (founded 1919) and flocked to the screenings organized by the Club des amis du septième art (CASA, founded 1920).

It was through CASA that Kirsanoff’s first film, L’Ironie du destin (believed lost), finally reached a sympathetic audience. Completed in 1922, the film tells the story of an old man and woman who meet on a park bench and exchange memories of their lost loves. It languished without distribution for almost two years and then caught the eye of Jean Tedesco when CASA programmed it as part of its regular screenings at a dance studio. A former editor of a women’s magazine, Tedesco had recently merged two film publications to create the definitive voice of the art cinema world, Cinéa-Ciné pour tous. However, he had bigger ambitions; seeing the success of the CASA screenings, he began to dream of a theater with full-time avant-garde programming.

Meanwhile, Kirsanoff was forging ahead with his second film, made, like the bulk of his work, outside commercial cinema on a tight budget. Little is known about Kirsanoff, who was born Mark David Kaplan in Riga, Latvia, according to some sources, or Dorpat, Estonia, according to others. He may or may not have played the cello in the Ciné-Max-Linder orchestra; he may or may not have played the violin in some of the Russian cabarets then popular in Paris. He did compare a film to a symphony in a 1929 Cinéa-Ciné pour tous interview, adding, “it’s wrong to say that images are words. They are notes or rather harmonies.” In the same interview he disparaged film adaptations of books and called intertitles the “bête-noire” of French cinema.

In fact, like his first film, Ménilmontant has no intertitles. The uninterrupted flow of images is only one reason for the film’s decidedly modern feel. Kirsanoff takes a melodramatic story of orphaned sisters seduced and abandoned in the poor, eastern Paris neighborhood that gives the film its name and turns it into something fresh and exciting. His technical virtuosity is on display in the stunning opening montage, a murderous sequence worthy of Hitchcock, and in the effective use of jump cuts thirty-odd years before Godard and the French New Wave. Kirsanoff’s accomplishment is all the more impressive considering that the atmospheric superimpositions and dissolves were done in camera.

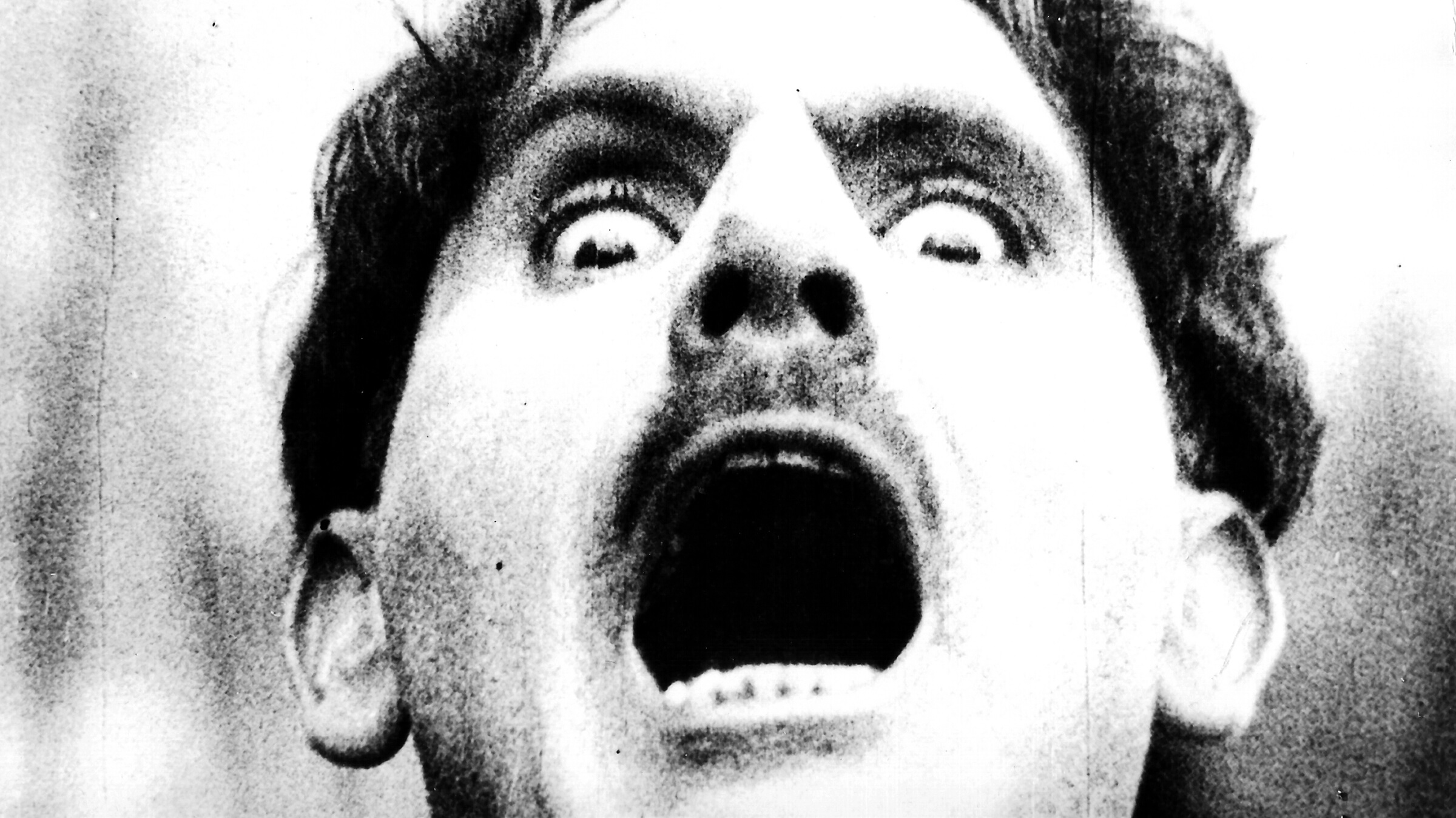

In addition to technique, the film’s other strength is Kirsanoff’s wife Nadia Sibirskaïa in the lead role as the younger sister. His constant and close collaborator (she claimed in a late life interview that she even filled in as director when Kirsanoff was ill), Sibirskaïa—who was born Germaine Lebas in Brittany—is a subtle, naturalistic actress, with eyes large and expressive enough to rival Lillian Gish’s. She is a mesmerizing film presence, whether reacting in horror to the death of her parents or waiting on a deserted street for her faithless lover.

Jean Tedesco programmed Ménilmontant to open the second season of his newly established art cinema, the Vieux-Colombier, in January 1926, and the film was an instant success with the art-house crowd. Historian Richard Abel wrote in French Cinema: The First Wave that the film “helped assure the success of the Vieux-Colombier and soon became a major film on the ciné club and specialized cinema circuit.”

In the fall of that same year, Man Ray’s surrealist short Emak-Bakia also premiered at the Vieux-Colombier. Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia, Ray was as reluctant a filmmaker as Kirsanoff was determined. He supported himself with photography but considered his paintings and assemblages his real art. Ray had only begun to dabble in film when domineering dadaist poet Tristan Tzara commanded him to produce a film for a soiree of contemporary art in 1923. Then in his dada period, Ray obeyed and Retour à la raison (Return to Reason) was the result. He cobbled together random footage he had shot, augmented it with his “rayograph” technique, which involved placing three-dimensional objects on light-sensitive material and exposing them. He had never tried the technique on film, but, pressed for time, he scattered thumbtacks over strips of film and developed them. The film broke twice during the projection (Ray didn’t know enough to edit with cement and not glue) and the evening degenerated into a brawl between dadaists and surrealists, but the thumbtacks danced on-screen and the technique has stayed in the experimental filmmaker’s toolbox ever since.

The man behind Emak-Bakia was Arthur Wheeler, an American stockbroker on vacation in Biarritz. Impressed with Ray’s photography, Wheeler offered to bankroll a film and was shocked when Ray insisted that all he needed was ten thousand dollars (half of which Ray used to buy a new camera). The film was shot in part at the Wheeler villa, which gave the film its name (a Basque phrase usually translated as “leave me alone”). “I drove down and lived luxuriously for a few weeks,” Ray wrote in his autobiography, “shooting whatever seemed interesting to me, working not more than an hour or two every day.” Whereas Kirsanoff’s bleak winter shoot is evident in his actors’ frosty breath, Emak-Bakia radiates the sun-drenched pleasures of the Basque coast.

Like Ménilmontant, Emak-Bakia is a catalog of film techniques. Ray reused the rayograph footage from Return to Reason, created abstract shots with distorting mirrors and spinning objects, and mixed stop-motion with live action—Jacques Rigaut, “the dandy of the dadas” is the man who sets the shirt collars twirling, and Ray’s lover Kiki, a Montparnasse fixture, is the woman with the painted eyelids in the final shot. When he introduced the film at the Vieux-Colombier that fall, Ray warned the audience, he later wrote, that ”my film was purely optical, made to appeal only to the eyes—there was no story, not even a scenario.”

Ray made one more film, Les Mystères du château de dé (1929), while Kirsanoff plugged away, mixing avant-garde shorts with more commercial features, until his death in 1957. Their films of the 1920s not only share a daring inventiveness but capture a distinct moment in time, when cinema fused with the art world and the possibilities of both seemed unlimited. In January 1922, Henri-Pierre Roché (then living the life that formed the basis for Truffaut’s Jules et Jim) described an evening party: “Marcel Duchamp projected his film experiments and geometric dances on the silvered side of a piece of bathroom glass—the result, expressive and quite fantastic, surely exploitable.