John Ford’s name is inextricable from the myth of the American West. The caustic grand old man with an eye patch made classic westerns such as My Darling Clementine (1946) and The Searchers (1956), shooting in the iconic Monument Valley and helping create the larger-than-life personas of actors such as James Stewart and John Wayne. Yet Ford also had a silent film career, first working with John Wayne in Hangman’s House (1928), Ford’s last feature of the silent era. By the time they met, Ford had been in the film business for 14 years, with seven silent shorts and 48 silent feature films to his credit. In these years, Ford developed his filmmaking skills, his famous rough, tough personality, and his passion for stories depicting the men and women of the American West.

Since the 1850s, the western had been a popular genre in literature, music, theater, photography, and art. Some of the earliest films were actualities of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, shot by Thomas Edison’s company in 1894, and fiction films such as Edison’s Poker at Dawson City (1898) and Edwin S. Porter’s groundbreaking The Great Train Robbery (1903). Westerns were promoted by the film industry as purely American, the first genre indigenous to the U.S.

John Ford would seem to be an unlikely chronicler of the American west. His parents emigrated from Galway and Kalona, Ireland, to America in search of opportunity. Ford was born John Martin Feeney in 1894 and grew up in Cape Elizabeth and Portland, Maine. It was his older brother Francis, who became an actor, producer, and director, who provided the new surname of Ford. Francis claimed that the name came from the surname of the famous car maker. John’s version was that his brother adopted the name while working as a stand-in for actor Frank Ford. John was known in high school as “Bull” Feeney for his football exploits running with head lowered, through defensive lines. He didn’t display much interest in classes with the exception of history. He also wrote stories, which he tried to sell, unsuccessfully, to magazines. Francis began working in movies in 1907, and, after graduating from high school in 1914, John followed his brother to Hollywood. Already a well-established western director, Francis gave John the opportunity to learn all aspects of filmmaking. John’s first film job was as a handyman, stuntman, prop man, and production assistant. He later worked for Francis as an assistant director and actor. Working on a Francis Ford picture meant lots of action: on-location shooting, horseback riding, performing stunt work, and handling explosives. One accident put John in the hospital for several weeks. Three years later, John got his first directing job, The Tornado (1917), for Universal.

That same year, Ford met his next major influence, mentor, and first leading man—Harry Carey. After directing three films, Ford was recommended to the actor, who was looking for someone to direct his next picture. Carey convinced Universal’s founder Carl Laemmle to assign Ford to the job. Like Ford, Carey was an unlikely westerner. Born in 1878, he grew up in a wealthy East Coast family but abandoned his ambition to be a lawyer when he wrote a play, Montana, around 1906, and toured with it for the next few years. The play featured a live horse onstage. Carey had read that any play with a horse in it would be a sure-fire hit, and it was. In 1909, he was hired as an actor by D.W. Griffith and the Biograph Company. He took a short break from Biograph in 1914 to write and direct two films, The Master Cracksman and Mcveagh of the South Seas. In 1915, he joined Universal and soon settled into mostly western roles, rapidly gaining wide popularity.

Carey created a unique western figure, often playing a regular joe instead of a dashing cowboy hero. He and Ford had their own unique way of working together. Carey’s wife, actress Olive Carey, recalled, “They would talk, talk, talk, late into the night and Jack [Ford] would take notes … and the next day they’d go out and shoot it.” Ford tested the waters with Carey on only two short films before jumping into directing feature films, returning only a handful of times to shorts. Ford and Carey pitched an idea for a feature film to Universal, which rejected it and told them to continue making two-reelers. Soon after, they told the studio that all their film stock had fallen into a river. Universal gave them another 4,000 feet of film and with it Ford made his first feature Straight Shooting (1917).

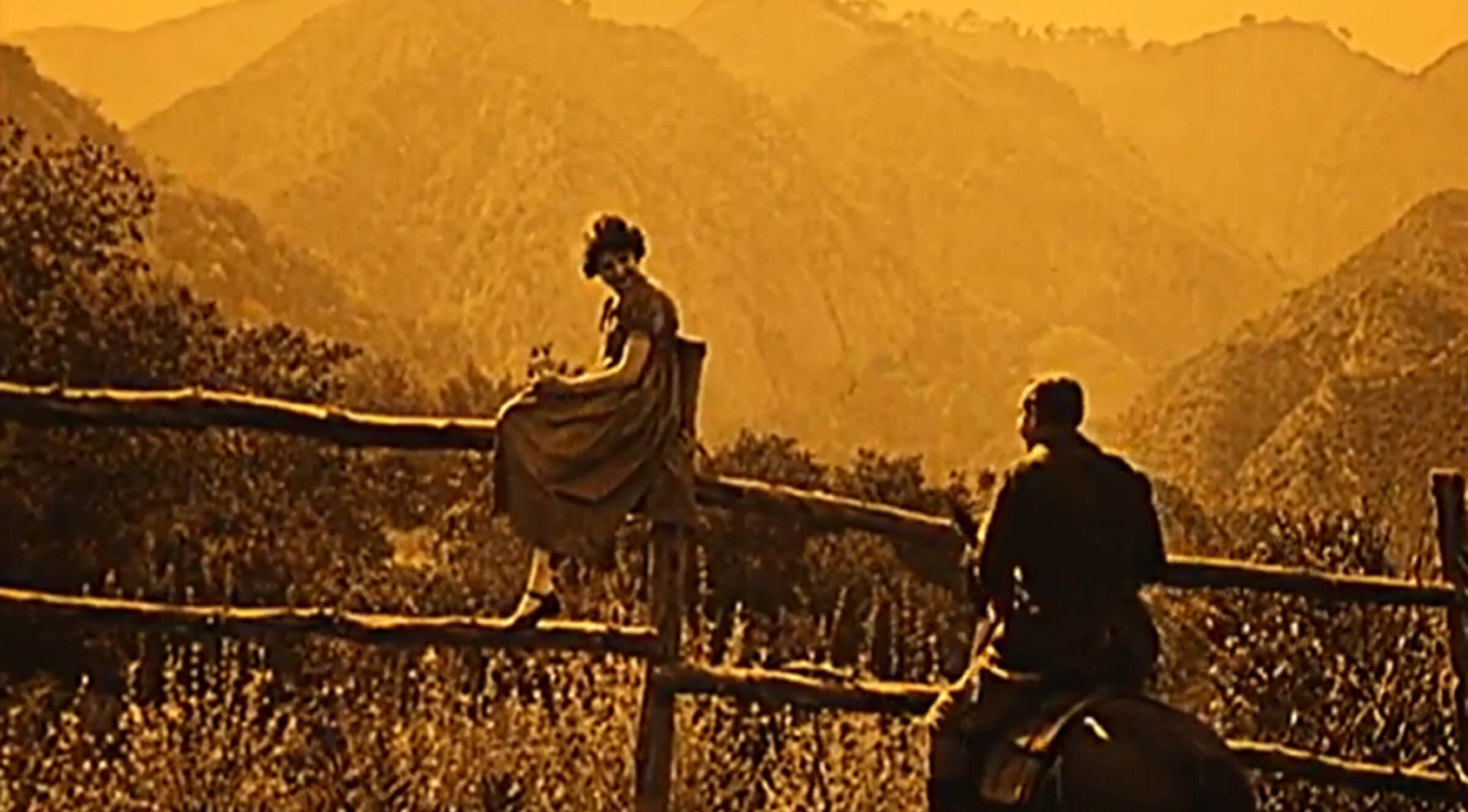

Bucking Broadway (1917) was Ford’s fourth feature and sixth film with Carey. A rare example of Ford’s very early work, it is one of only a handful of his silent films to survive. Yet already, his distinctive style is evident, in the adept composition of vast landscapes, and the humor in scenes such as cowboys on horseback racing down New York City’s Broadway (actually shot in Los Angeles). For years considered a lost film, a print of Bucking Broadway was discovered in France and restored in 2003 by the Centre Nationale de la Cinématographie (CNC).

After nearly four productive years, tensions over salaries and Ford’s desire to move on finally broke up the Ford-Carey team, and Ford moved on from Universal to Fox in late 1920. Four years later, Ford created his first western epic, The Iron Horse (1924), a film about the strength, endurance, and heroism of those who built the railroad. The New York Journal praised the film: “I stood up—I admit it—and cheered.” Ford followed this success with a number of smaller films. Highlights include the star-studded Three Bad Men (1926) with Tom Mix, Buck Jones, and George O’Brien, and Mother Machree (1927).

Both Ford and Carey easily made the transition to talkies. Carey, who was already in his 50s, also transitioned into character roles. One of his most memorable portrayals, as the vice president in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), earned him a best supporting actor Oscar nomination. He and Ford remained friends but worked together only one more time, in The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936). Carey died in 1947. The following year, Ford remade one of Carey’s starring vehicles, Three Godfathers (1916), which Ford himself had already remade, with Carey as star, as Marked Men (1919). Ford’s 1948 Three Godfathers carried this dedication: “To Harry Carey – Bright Star of the Early Western Sky.”

Ford’s later films are notable for their simple, unadorned yet majestic cinematography. This simplicity developed out of necessity during the silent era, when he made films quickly and with small budgets. It is often said of Ford that his brusque personality and his insistence that he was only a craftsman were ruses to protect his artistic aspirations. Ford denied such aspirations, saying that makers of artistic films don’t find steady work. “The secret is to turn out films that please the public, but that also reveal the personality of the director…. On their success hangs my freedom of action.”

Presented at SFSFF 2006 with live music by Michael Mortilla