This feature was published in conjunction with the screenings of The Cameraman and Our Hospitality at SFSFF 2019

As a tyke Buster Keaton developed the necessary body calluses to take his own pratfalls. As one of Three Keatons on vaudeville, he was cast as the “Human Mop,” variously mock-strangled, kicked, and tossed about, sometimes sent flying into the orchestra pit by father Joe. According to family legend, the conditioning started way earlier than his stage debut and even before he earned the nickname Buster for emerging unhurt from a fall down a flight of stairs. “About two months before I was born,” he recounts in My Wonderful World of Slapstick, “my mother was in an accident. Pop was driving her to their boardinghouse in a small Iowa town but got out of the buggy to buy something at the general store. Startled by a flash of lightening, the horse bolted. He raced around the corner at such speed that the carriage went over on two wheels, throwing my mother on the ground.”

He goes on to describe a black-and-blue childhood, involving cyclones, washer wringers, and bricks, all fodder for the lore of the “Little Boy Who Can’t Be Damaged.” It is true that his father knocked him out cold twice during a performance, first by throwing him into a backdrop, which gave way to a brick wall behind, and, another time, inadvertently kicking Buster in the head. Backstage wasn’t very safe for young Keaton either. In a Chicago theater he stepped on a rusty nail, which a prop man yanked out with a pair of pliers. The doctor who treated his festering foot days later in Milwaukee said any further delay and Buster would have had lockjaw … and we haven’t even gotten to the films yet.

THE ELECTIC HOUSE

During the first time trying to make this two-reeler about a struggling botanist hired to wire a mansion with gadgetries of convenience, Buster broke his ankle. “The accident happened on a studio-made escalator,” he recalls, “when the sole of my slap shoe got caught in the webbing of the moving machine.” No one could unplug the contraption fast enough and his bone snapped, the escalator still moving him upward. But it wasn’t over. “As I got to the top,” he goes on to say, “I was tossed for twelve feet.” They suspended production on the film, picking up again months later.

THE THREE AGES

In the Modern episode of Keaton’s first feature-length film the hero is supposed to leap from the roof of one building onto another. Performing the stunt, Keaton misjudged the distance and slammed into the oncoming wall, barely hanging on with his fingertips. When he couldn’t keep his grip, he dropped thirty-five feet into a safety net. The cameras caught it all and Keaton decided to incorporate the accident into the film. After taking three days off to recover, he completed the fall for the camera, dropping down into two awnings then grabbing onto a drainpipe, which then dislodges from the building and sends him swinging through a window and down a firehouse pole.

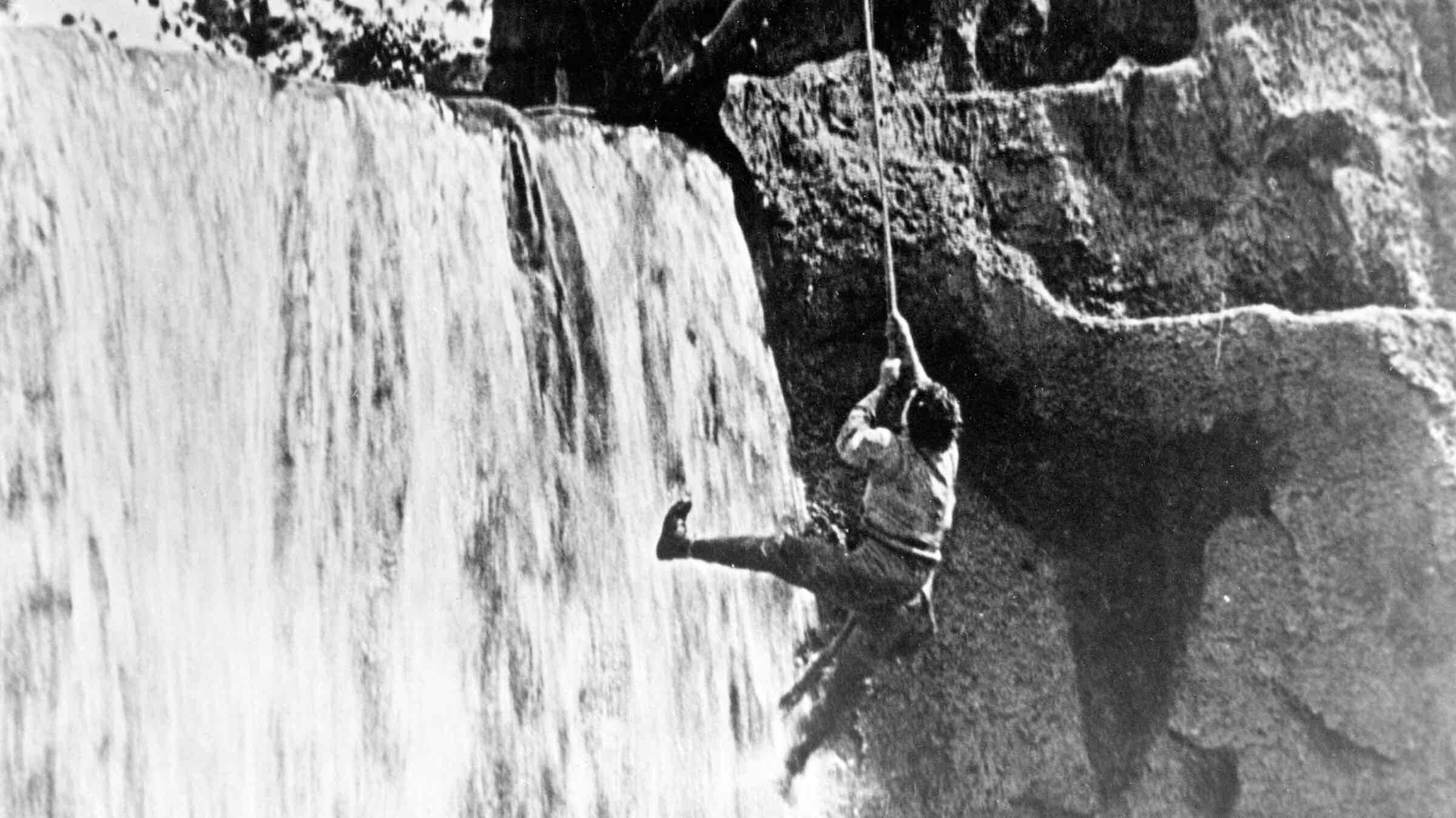

OUR HOSPITALITY

It is Keaton, rather than costar Natalie Talmadge, in need of rescuing during the whitewater rapids scene when the safety wire broke and sent him whooshing down the Truckee. He ended up saving himself by grabbing onto an overhanging branch at a bend in the river. According to Marion Meade’s 1995 biography of Keaton his first words when they found him soaking wet on the river bank were, “Did Nat see it?” True to Keaton form, he left the terrifying sequence in the finished film.

SHERLOCK JR.

When Keaton complained of headaches a doctor asked if he had ever sustained a skull or spinal fracture. In his memoirs, Keaton recalls: “I had to think for a while before figuring out that it must have happened during a sequence of Sherlock Jr. … I ran along the top of a train and grabbed a rope dangling from a water tower to swing off to the ground. This set up the gag for the spout to open. But we underestimated the volume of water that would fall on me from that ten-inch spout. The stream struck me so hard it tore loose my grip on the rope. I fell back on the track with my neck snapped down square across the steel rail.” In the film, Buster gets up and runs off in the same shot.

THE NAVIGATOR

Presumably with his still-fractured cervical vertebra, Keaton embarks on his next film and almost chokes to death. He wrote about shooting the run-up to the underwater scene for which he donned a 220-pound diving suit: “Smoking a cigarette when the girl tried to put my helmet on. I left the cigarette in my mouth while I reached up to help her get it on. Accidentally, she gave it a half twist, locking it. The smoke from the cigarette threw me into a frenzy of coughing. Fortunately, Ernie Orsatti, the [future] St. Louis Cardinals’ ballplayer who was working with our crew, noticed the trouble I was in and twisted off the helmet in the nick of time.”

THE GENERAL

As a railway engineer in the South who attempts to sabotage a Union mission during the Civil War, Keaton performs many dangerous maneuvers on a moving train—but his only injury was getting knocked unconscious by cannon fire. He wasn’t the only one put in danger, though. According to Motion Picture News, in the famously expensive shot of the train trestle giving way and the locomotive plunging into the water, cameraman Devereaux Jennings fractured his arm when tumbling debris crashed into his boat in the river below where he was photographing the action.

STEAMBOAT BILL JR.

Most remarkable of all is that in his last film before he signed over his independence to MGM Keaton didn’t get hurt at all—unless a fast ball careering into his face and breaking his nose during an off-hours baseball game counts. Shooting what might be his most spectacularly perilous stunt—rigging a house to collapse around him during a storm—he’s left standing, completely unscathed.