This feature was published in conjunction with the screening of The Dumb Girl of Portici at SFSFF 2017

What’s the point of having a cast of thousands if they can’t rise up in revolt once in a while? Filmmakers quickly realized that masses of extras on the screen would attract masses of customers to the movie theaters, especially with spectacle and chaos in the offing.

Beginnings: Torn from the Headlines

Smaller sets and limited cinematography options meant that the earliest filmmakers had to satisfy themselves with casts of dozens but they compensated by diving into hot political topics. Nearly two decades before Battleship Potemkin, Lucien Nonguet recreates the Odessa mutiny in the 1906 film La Révolution en Russie. The deck of the battleship is plainly a painted set but the cast makes up for any deficiencies in realism by enthusiastically hurling around mannequins dressed in officers’ uniforms. Limitation can lead to innovation and such is the case with the ninth episode of Georges Méliès’s 1899 series L’Affaire Dreyfus, which ends with the pro- and anti-Dreyfus factions rushing the camera. The comparatively cramped space of the Méliès studio means that the performers have nowhere to go but downstage and the result is an unusually kinetic sequence for the period.

Scope: Bigger Gets Better

As the epic spectacle continued to be perfected throughout the 1910s by directors like Giovanni Pastrone and D.W. Griffith, portrayals of uprisings, strikes, and revolts grew larger as well. The 1899–1901 Boxer Rebellion, or Yihequan Movement, provides an example. The West’s perspective of the event had been shaped by newsreels of marching British soldiers and small bands of actors dressed in Chinese garb committing trick photography beheadings. When Albert Capellani adapted this history for the screen in the late 1910s, he was no stranger to uprisings, having directed a nearly three-hour adaptation of Les Misérables in 1912. For 1919’s The Red Lantern, he takes the still-fresh images of the previous decade and turns the rioting Chinese citizens into a living wave made up of hundreds of extras that undulates back and forth against makeshift barricades.

Frenzy: All Riled Up for $2 a Day

The French Revolution provided an excuse for filmmakers to embrace the more emotional aspects of revolution. In his saucy historical epic Madame Dubarry, also from 1919, Ernst Lubitsch whips his sans-culottes into a frenzy that cannot be contained by the massive sets; it seems to spill off the screen. They burst through the streets leaving battered soldiers, hanged aristocrats, and a decapitated Pola Negri in their wake. Back in Hollywood, Rex Ingram, a master of light, smoke, and shadow, presents a moody, stylish French Revolution in Scaramouche (1922). Fires smolder as palaces are stormed, bodies thrown, limbs hacked, women in wild hair and full makeup lead the charge with swords drawn. It is violent, anarchic, and strangely beautiful.

Primal Urges

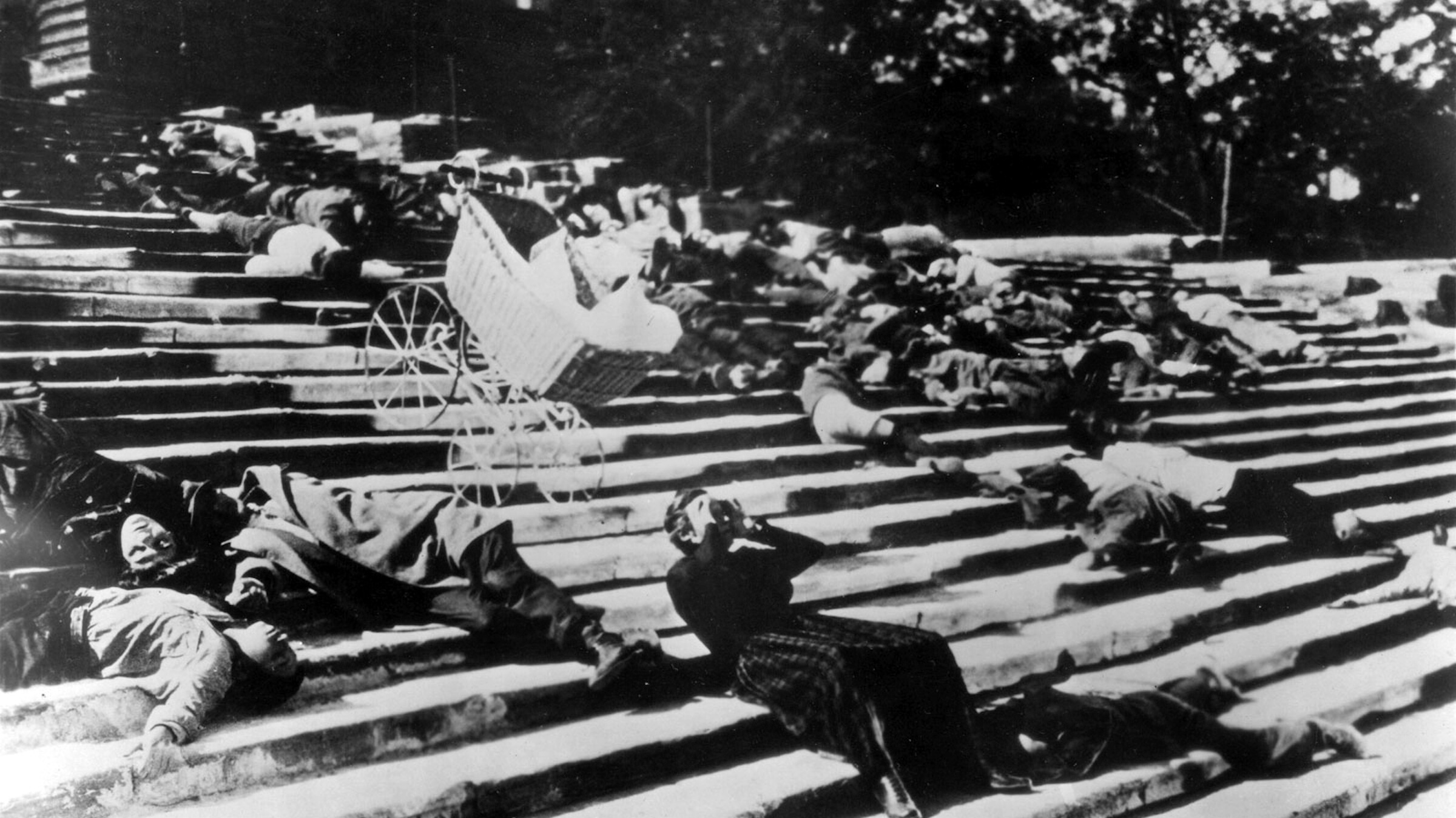

Food triggers a revolt in Lois Weber’s The Dumb Girl of Portici and Sergei Eisenstein famously made maggot-ridden meat the spark that ignites a mutiny in Battleship Potemkin. In October, he further embraces the primal in the service of propaganda. Revolutionaries are scattered with rhythmic machine-gun fire and the tsarists rise up in counter-protest, bourgeois ladies gnawing at the protesters’ flags with their teeth. Hollywood wasn’t about to let an event as cinematic as the Russian Revolution pass it by, but American filmmakers had the luxury of sidestepping the political aspects if they so chose. The revolution of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Volga Boatman is not caused by complicated partisan factors so much as poor boys longing for rich girls and vice versa. DeMille circumvents any discussion of communism by essentially filming the French Revolution with furrier hats and sprinkling “comrade” throughout the intertitles, leaving lust as the prime mover in the plot.

On Location, Location, Location

While riots, mutinies, and uprisings were often filmed within the controlled conditions of a movie studio, plenty of filmmakers went on location to capture the action for newsreels and to lend authenticity to fiction films. Such ventures were invariably lauded—and often exaggerated—in marketing materials. The 1928 British production Emerald of the East portrays an uprising of a mountain tribe against a pro-Raj ruler and was partially filmed in and around Gwalior, center of the actual 1857 rebellion. Press releases crow that the filmmakers were granted use of thousands of soldiers as well as the state elephants and jewels. The slick action scenes feature rebels weaving through the underbrush but they are soon persuaded to lay down their arms in a rare instance of cinematic revolt being resolved diplomatically. Of course, the real struggle for Indian independence was not settled with anything as simple as a few minutes of friendly title cards.

Camera Ready

While Georges Méliès’s protesters rushed the static camera back in 1899, Raymond Bernard’s The Chess Player (1927) takes the opposite approach, benefiting from technological innovations that allowed for more fluid movement. By now cameras had been mounted on anything that moved and swooped through the air, the streets, ballrooms, circus tents, and sometimes even down a performer’s throat. The Polish soldiers in Bernard’s film mutiny against the occupying Russians and the fully unchained camera charges into the action, lurching wildly through the combatants and dragging the audience with it. Just like being there but without the contusions.