A selection of Georges Méliès short films played throughout the festival. Special thanks to Lobster Films.

On December 28, 1895, in the Grand Café on le boulevard des Capucines in Paris, a 34-year-old magician sat among the other 30-odd guests, which included the directors of the Folies Bergère and the Grévin Wax Museum, waiting for the program to begin. Owner of the 200-seat Théâtre Robert-Houdin since selling his share of his father’s luxury shoe business in 1888, he performed illusions like his 1891 act entitled, American Spiritualistic Mediums, for which the decapitated head of the loquacious Professor Clodien Borbenfouilles is placed in a bowl yet keeps talking. He closed his shows with magic lantern projections, designed to spook and delight Parisians on a night out in the late 19th century. Sitting that night in front of a blank screen in the Salon Indien, he did not expect to be impressed. “Have we been brought here to see projections?” Georges Méliès complained to the person sitting nearest him. “I’ve been doing these for ten years.”

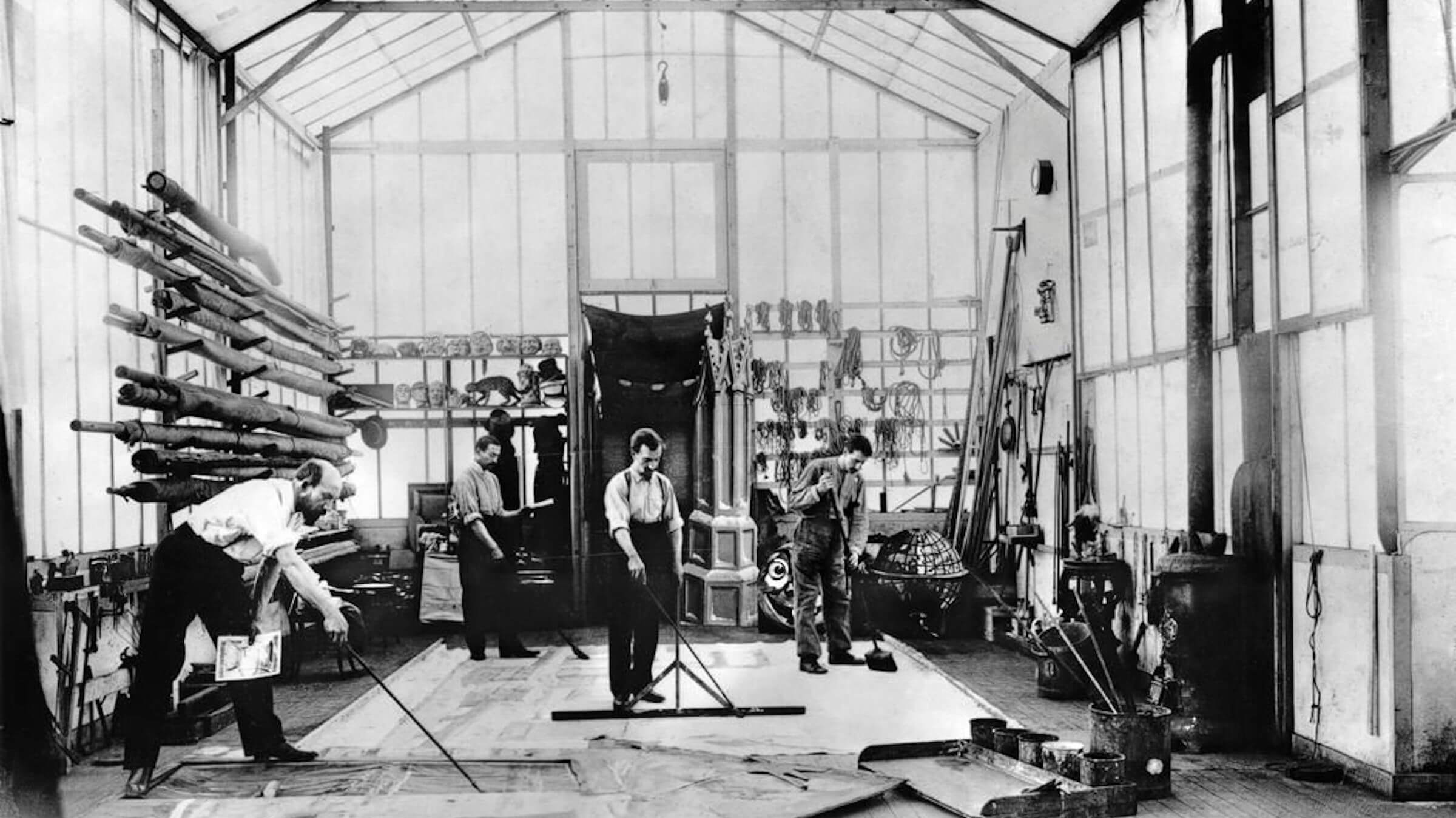

By the end of the program of Lumière brothers’ actualités, Méliès had changed his tune, offering 10,000 francs for the moving image contraption the very next day. His proposal declined, he instead bought a Theatrograph from Britain’s R.W. Paul and began screening Edison shorts at the end of his shows. By spring 1896, he had developed a camera of his own and made his first film, Un partie de cartes, a one-minute imitation of the Lumières’ Partie d’ecarté of the previous year. By December, he inaugurated his company Star Film with its slogan, “The Whole World Within Reach,” and began construction on his own glasshouse studio in Montreuil.

He built a diverse catalog, providing actualités, reenactments of current events, and advertising films, dramas, comedies, and even stag films. It was the epiphany he had after his camera jammed then restarted on la place de l’Opéra that came to define Méliès as a filmmaker. Watching the footage later that day, he reported: “I suddenly saw a Madeleine-Bastille omnibus change into a hearse and men into women.” He realized that by simply stopping the camera to change the scenery, he could create the same illusions he had been performing on stage. His October 1896 film Escamotage d’une dame chez Robert-Houdin (The Vanishing Lady) shows Jehanne d’Arcy—his mistress and the future second Madame Méliès—instantly replaced by skeleton. The trick film was born. Disappearing ladies, removable body parts, and trips to the moon made his films so popular that American film distributors copied and resold them under their own banners. Sigmund Lubin once tried to sell Méliès himself his own 1902 A Trip to the Moon. Despite the unscrupulous competition (even a little because of it), Georges Méliès dominated one quarter of the worldwide film industry by 1909.

The Méliès operation was a one-man show. He managed the theater, wrote, produced, directed, edited, and acted in his films, as well as designed the sets and costumes. For A Trip to the Moon, the first science fiction film ever made, he sculpted the now iconic clay moon where the astronomers land their spaceship. But as quickly as his success surged, it seemed also to decline. Changing production techniques and tastes of audiences combined with his own personal tragedies, forcing him to sell his theater in 1915. By 1923, he had dismantled his studio and sold off all his scenery, props, costumes and, because he had no place left to store them, destroyed all his negatives. We know of him today because film critic Leon Druhot who, after discovering Méliès selling toys at a Paris train station, began to write about him. One of cinema’s first storytellers became, fittingly, the first to be rediscovered.