Cinema, as it ages, does not remain merely art and entertainment but also evolves into a panoply of unique cultural qualities—captured time, shared memory, social evidence, cured history sliced for sandwiches, sociopolitical realities fermented into nostalgic headtrips. The range of organic possibilities comes alive when you’re watching Vasili Zhuravlyov’s Cosmic Voyage (1936), a genuinely obscure silent-Soviet artifact that appears to not have been mentioned in any film history book known to the English-speaking world. This is hardly just an old silent—it’s a dream retrieved from the long-lost collective consciousness as well as an important progenitor of many of science-fiction film’s integral genre tropes. Not incidentally, Zhuravlyov’s almost unbearably quaint proto-space-age lark is the only film to which pioneering rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky lent technical assistance. (The story’s futuristic space agency is prominently titled, the Tsiolkovsky Institute of Interplanetary Communication.) A groundbreaking amateur rocket engineer and physicist idolized after his death (in 1935) by Soviet culture, Tsiolkovsky made sure that astronautic considerations like landing shock and oxygen supplies were key to the scenario, making it the first semi-accurate cinematic depiction of space travel (and ahead in several ways of the H.G. Wells-derived British epic Things to Come, released that same year).

As a primal genre text, the film is, of course, beguilingly naïve but also enthusiastically serious about wanderlust, space exploration, and Soviet pride. The film’s credits and full title, Kosmicheskiy Reys: Fantasticheskaya Novella, explicitly suggest that the narrative was adapted from Tsiolkovsky’s 1893 speculative novel On the Moon, but it’s more accurate to note how much the tale is derived and/or cadged from Fritz Lang’s Woman on the Moon (1929), down to the who’s-boarding-the-rocket intrigue and the makeup of the resulting ensemble (an old scientist, a blonde, and a precocious young stowaway). But at roughly one-third the length of the Lang film, Zhuravlyov’s bouncy launch is by far the breezier affair, as much a result of the sheer daydreaminess of Soviet cinema (relative to the monolithic, depressive moralism of pre-Nazi German film) as of its running time.

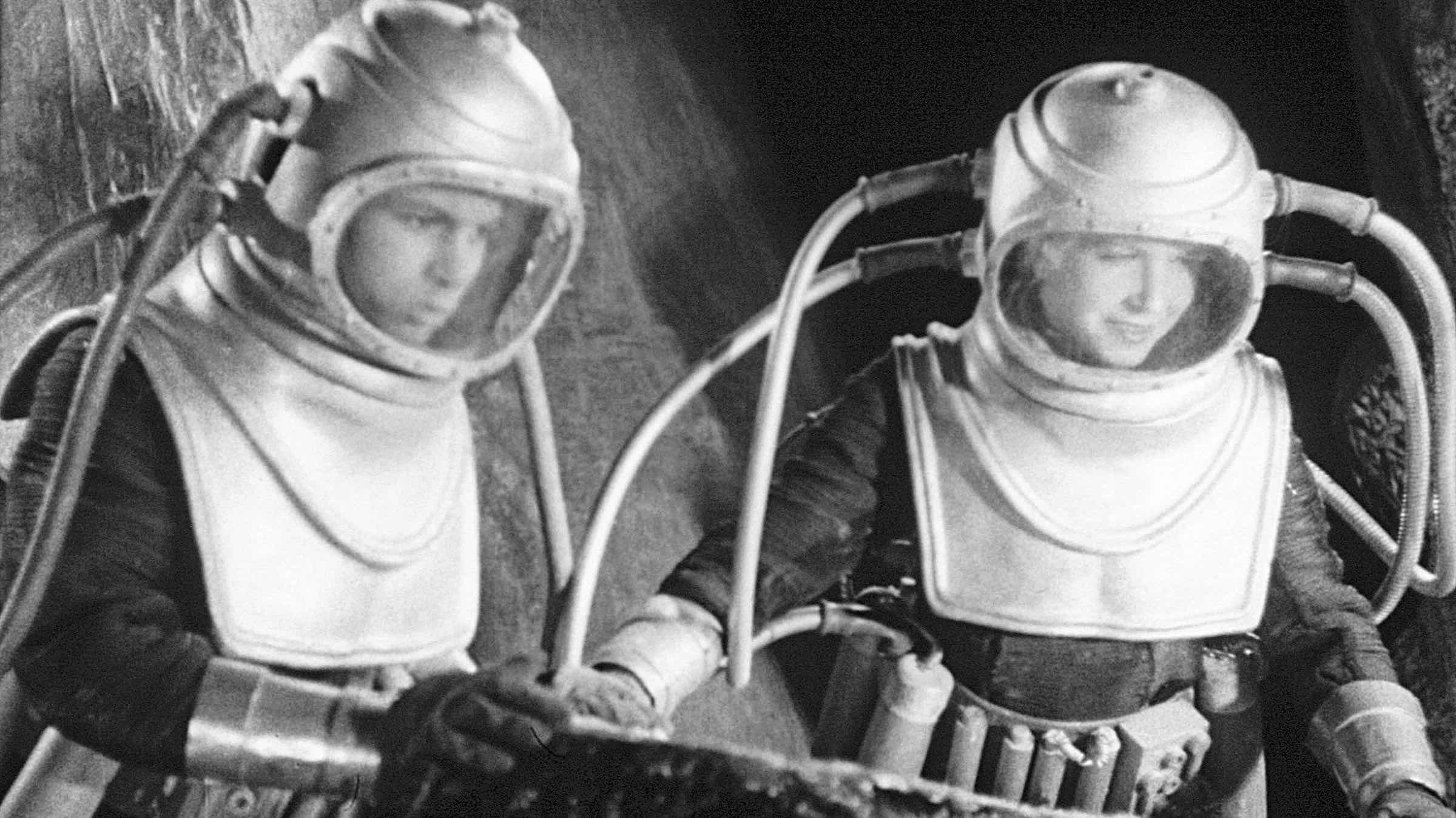

The movie’s visual essence is unforgettable, both for what is prototypical about it (the Soviet way with monumental framing, especially heroic close-ups, is quite unlike any other national tendency and remained so through the films of Mikhail Kalatozov in the ’50s and ’60s), and what is entrancingly particular—a steam-punky design arsenal that includes Rodchenko-esque diagonals, Futurist set design, spellbinding miniature effects, and the stop-motion animation work, reminiscent of Ladislaw Starewicz, of The New Gulliver vet Fodor Krasne, which has tiny animated cosmonauts running and leaping weightlessly across a rocky tabletop Moon surface. (Such eye-popping moments make movies like these feel closest to embodying the imaginative play of children—and closest to reminding us that “pretend” is cinema at its most elemental. In one breath-holding early sequence, the camera dollies through a hangar loaded with rockets and tiny animated workers, making the film at that instance as much a toy as a movie.) In fact, production on Cosmic Voyage was initiated after a request by the Komsomol, the USSR’s Communist youth league, for more movies to be made for kids. Soviet youngsters could hardly have helped being delighted with the frantic, vividly imagined alt-world conjured in Cosmic Voyage; the clearest indication anyone could need for its success as a matinee crowd-pleaser among the underage hoi polloi is the objection made by the Soviet censors who complained about the animated cosmonauts’ frivolous “bouncing” on the Moon and had Krasne’s name struck from the credits.

Frivolities abound—no film has ever enjoyed the spectacle of spaceship weightlessness so much, even if the wires are clearly, endearingly visible. What’s delivered most liberally today in Zhuravlyov’s tale of zesty exploration and subsequent scramble for survival and rescue in the lunar canyons is the delicate esprit of Soviet hopefulness, the culture’s teary, exuberant utopianism. The nation’s singular propagandistic personality, whether issuing out of films or poetry or art or music, always seemed on the verge of an emotional breakdown, with the insistence on noble sacrifice and natural greatness covering up a fragile and heartbroken hysteria. Soviet films in general, from Eisenstein to Chukrai, could be seen as naïve and vulnerable children, quick to be overwhelmed with righteousness or rage but most often so besotted with either joyful optimism and swooning grief, often both in turn, that you can worry for the health of their unstable psyche. At the very least, it’s easy to be terribly moved by the films’ naked emotionalism, particularly since it expresses not necessarily a filmmaker’s aesthetic, but an entire hornswoggled country’s rueful agony and fantasized ecstasy.

The key to Cosmic Voyage’s vibe is the way it expresses a society stricken with mandatory radiance, and therefore in need of a fantastical escape from the fantasy of its official life. Twentieth-century Russians always had a special relationship with science fiction because everything authorized in the Soviet Union was science fiction—ideological fantasies of progress, improvement, empowerment, and technological glory. In the USSR, a poster for tractors was science fiction. In turn, the outright science-fiction science fiction, like Cosmic Voyage, were among the most euphoric and fetishistic genre texts made anywhere on Earth. What was intended as sky-high propaganda comes off now—and maybe scanned in the mid-century for natives, too—as feverish playground deliriums, struck deep with a chord of pervasive elegiac melancholy.

In any case, the preponderance of evidence suggests that the population of the USSR didn’t buy into the films’ pulpy propaganda so much as put up with it and maybe even enjoyed it for its simple escapist chicanery. Cosmic Voyage was almost certainly more fun than it was politically inspirational. But however built for audience accessibility—the film was made silent in 1936 in order to maximize its viewership in the outer republics, to which sound projection equipment was still slow in coming—Cosmic Voyage proved too escapist for the needs of the Soviet planners and was quickly pulled from theaters. Today, it’s a message lost for decades in space, poignantly brimming with needful Soviet daydreams we know never came true.

Presented at SFSFF 2014 with live music by the Silent Movie Music Company (Guenter Buchwald and Frank Bockius)