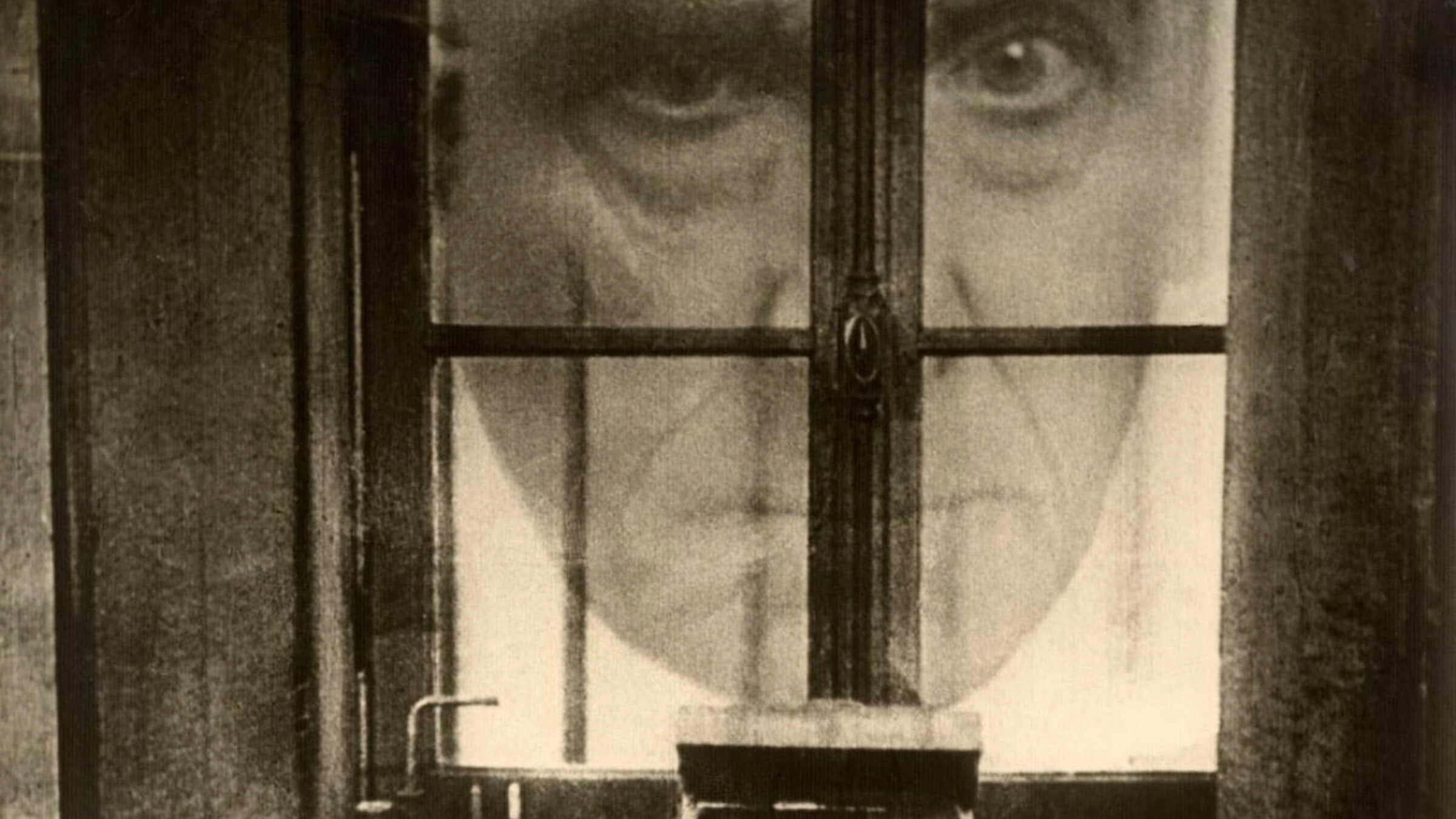

A good many years ago, while I was watching a videotape of Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932), my eight-year-old daughter came into the room and glanced at the screen for a few moments. What she saw unsettled her so much that she quickly walked away. She was disturbed not by any of the film’s more elaborately nightmarish details—the giant head of a murder victim hovering outside a window or the shadow of the one-legged soldier creeping back into his body—but simply a few frames of a face, without a mask or outré makeup, encountered outside of any narrative context.

The face is that of Sybille Schmitz, who had previously made a brief but impressive appearance in G.W. Pabst’s Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), playing a housemaid driven to self-destruction. Her performance in Vampyr as Léone, a young woman fallen victim to the vampire Marguerite Chopin, would be the most lasting legacy of a troubled life. (Her catastrophic final years, wracked by addiction and ending in suicide, provided the direct model for Fassbinder’s death-haunted Veronika Voss.) In that moment dominated by her face—the tail end of a sequence lasting barely two minutes—Schmitz enacts, in almost mediumistic fashion, the mortal combat between desire and revulsion as Léone tries to resist the vampirism that has already infected her and that finally asserts its full power.

The film that Dreyer described as a “waking dream” remains as labyrinthine as it was in 1932, perpetually forcing questions about what exactly is seen and who, in landscapes filtered through scrims of mist, is seeing it. The film invents its own language for mapping the intermingling of different worlds as the dead prey upon the living and the living behave like sleepwalkers under perpetual siege. Yet, for all the mist and splintered spatial continuity, everything feels uncannily palpable. The supernatural combat plays out not on fantastic sets but among grittily real locations: an abandoned château, an abandoned factory, an abandoned abbey, an abandoned mill.

The vampire who feeds on Léone’s lifeblood is no flamboyant Dracula or ogre-like Nosferatu but a white-haired woman who walks slowly with a stick; she might be a prosperous burgher of another century. We see little of her and hear less—her single line of dialogue being “Silence!” as she interrupts a supernatural dance party—but no spectator is likely to forget her stony, unpitying face. She delivers not a performance but a presence. Under her influence the human world becomes a zone of powerless entrancement.

The crucial moment—the momentary interruption of the trance—comes when Léone, rescued from a vampire attack, is swaddled in a blanket and propped in a chair. For two minutes the visual field is dominated by Schmitz’s face: her eyes open slowly, and she stares wildly up and around; her hands are clamped over her mouth, then slip away to reveal her face in a new light; her neck turns to expose the vampire’s puncture mark; her lips mouth words that do not emerge. Rapidly changing expression, she manages to cry out, “If only I could die!” Convulsive inner changes are conveyed through fleeting tics, tremors, hesitations. At last, as if under pressure, her mouth forces itself into a grin, and with bared teeth her face becomes a mask of predatory lust.

Add fangs and more lurid staging, and the scene is a template for many a vampire film to come. As filmed by Dreyer, it is like a sudden intrusion of fully expressed anguish, breaking through the prevailing somnambulistic lull. Invaded by a dark foreknowledge, Léone is at once possessed and fighting against possession. It is not the first or last time in Dreyer’s work that a woman’s face is the site of a life-and-death struggle, from Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) to Birgitte Federspiel as the resurrected Inger in Ordet (1955). In the case of Sybille Schmitz, he found an actor more attuned to that role than he or she was likely to have realized.

Presented on Friday, January 12, 2024, with live musical accompaniment by Timothy Brock conducting the San Francisco Conservatory of Music Orchestra