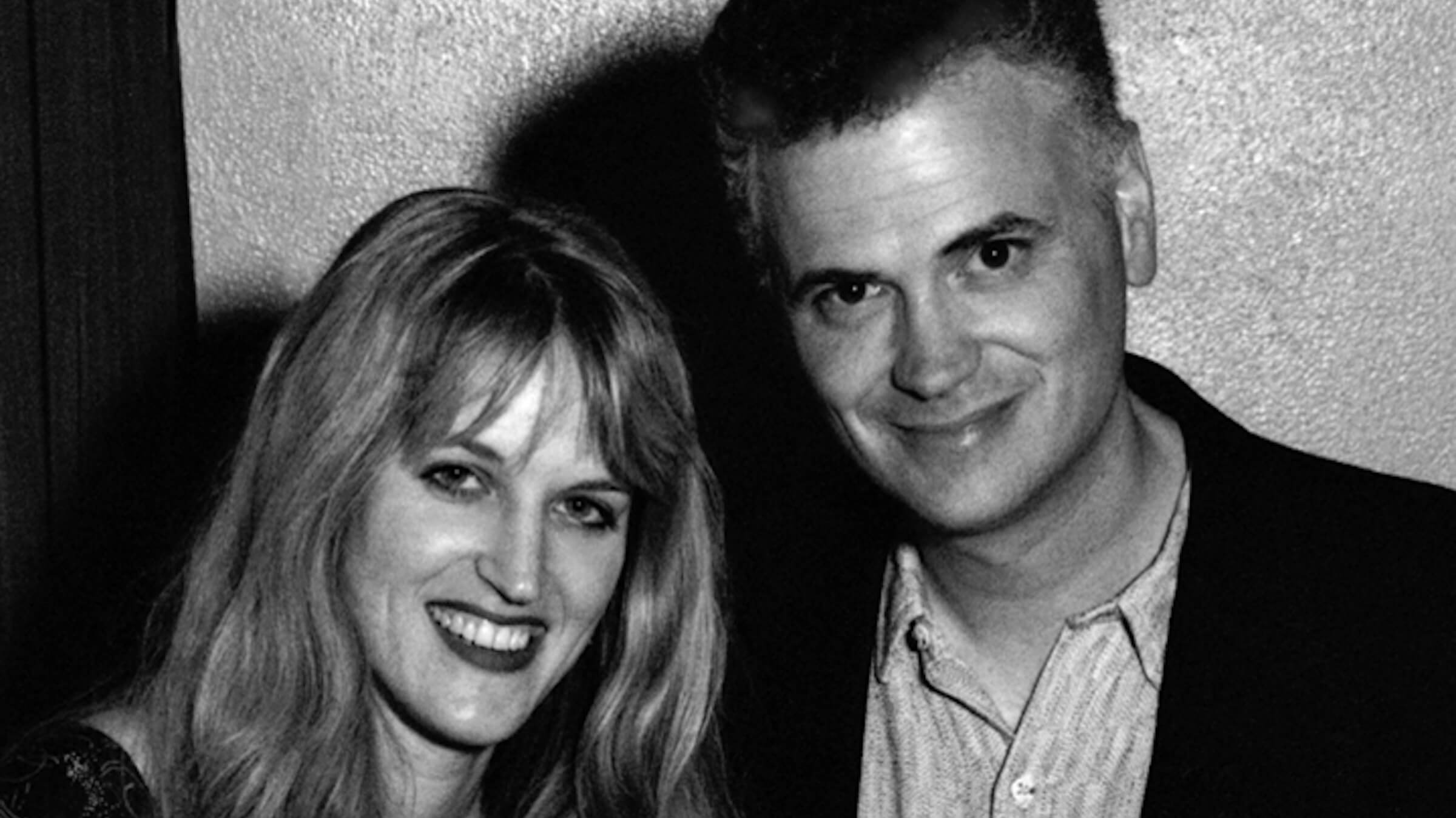

Founders Melissa Chittick and Stephen Salmons Look Back at the Early Days of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival

It takes more than a passion for silent film to put on a festival. Melissa Chittick had a film degree from UC-Santa Barbara, and Stephen Salmons had been making Super-8 silent films for years, but although Chittick volunteered at the Red Victorian movie theater, neither was working in film-related jobs when they decided to launch a silent film festival. From a stack of Nolo Press books, they learned the fundamentals of establishing a business and setting up a nonprofit. Next came a warm-up program at Frameline’s 1994 festival, Ernst Lubitsch’s I Don’t Want to Be a Man (1919). Then came two years of fundraising, developing the right mix of films, musicians, and razzmatazz (silent stars Fay Wray and Baby Peggy in person) to entertain and enlighten audiences—and resisting well-meaning supporters who urged them to hurry up and get started.

STEPHEN SALMONS When we started the festival, we didn’t know anybody in the film community. The only contact I had was my uncle, who was a professor of film at the University of Iowa, Richard Dyer McCann. He was kind of surprised when I told him what we wanted to do. But he said, “Well, the one thing I can do is share Kevin Brownlow’s phone number. I just ask that you use this responsibly.” I think he was afraid that we would call him up and embarrass him. We did a five-year business plan. Then it took months and months to figure out.

MELISSA CHITTICK One of the first press notices we ever got, we sent out a press kit, and somebody at the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, “From the ‘Who-Needs-Another-Film-Festival’ department.” We thought it would be important to start with a small event, to learn how it’s done. From that we learned a lot about how much it cost to do one show—and then it was a year or two where we started to build up the money. That’s when people started getting frustrated with us. People from other festivals said “Why don’t you show them at the Red Vic, why don’t you show them in sixteen-millimeter, why are you raising money, why are you building a board, you don’t need to do that.”

SALMONS We were never part of the network of film programmers.

CHITTICK We had this weird product, so we couldn’t share with them in the same way. We didn’t have new filmmakers, we didn’t have new directors, we weren’t the same thing. I always thought it was more like opera, or a museum.

SALMONS We had done demographic surveys. Overwhelmingly, people said we should do it at the Castro, so it took years to raise the money.

CHITTICK You have to look really professional if you want people to take you seriously. And I think that’s why for the very first festival [in 1996] we got half a page in the Datebook section of the Chronicle. But that’s the thing about admitting your dream in public. Once you tell people, you have to do it because it would be way too embarrassing not to.

SALMONS But I do remember that we did not necessarily think there would be a second silent film festival.

CHITTICK Another thing is, we never put anything on credit cards, ever.

SALMONS Because of her financial planning, we were never in the red once.

CHITTICK And that’s why we got so many grants.

SALMONS You could see right from the first year, we were trying to do a different kind of programming than someone who knows silent film would expect. We definitely wanted to send a message that this isn’t traditional programming, this is a unique perspective on silent film programming.

CHITTICK We were really conscious of trying to make it as entertaining as possible, not to make it too scholarly, not make it too dry.

SALMONS I remember early on, this thing that happened at the beginning of a screening, a little bit of restlessness. Somewhere around fifteen or twenty minutes in, people lock in, and suddenly, they’re completely on track with the art form. The first year, we sold a total of eighteen hundred tickets for three programs, Gretchen the Greenhorn, Lucky Star, a little bigger, and Ben-Hur sold out.

CHITTICK That first year, Randy Haberkamp of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences introduced the very first program. He presented us onstage with two Lubin film cans with one-minute film reels inside. We still have them, with the original ribbon that tied them together. He said he hoped that the festival would be a success and last for years and years.

SALMONS And whatever we had learned that year we incorporated into our knowledge going forward. I think that’s what makes [Melissa] so smart. She’s not just the person who wants to show movies because she “just looves them!” She’s serious about making something happen. We spent most of the time doing nuts and bolts stuff. But having Fay Wray attend was very exciting—that was meeting Hollywood royalty.

CHITTICK We had dinner with her, and she talked about “Mr. Stroheim”—how Mr. Stroheim had a thing for her.

SALMONS She really appreciated that it was The Wedding March that we wanted to have her here for, not King Kong. She said, “I’ve had enough of King Kong. Stroheim was a genius, and it’s great to have a chance to celebrate him.”

CHITTICK What I’m thinking of is John Gilbert’s grandson. He had the manner of John Gilbert …

SALMONS [Melissa] flipped for him! Gilbert’s daughter Leatrice and King Vidor’s daughter Belinda met each other for the first time at the festival, and they loved each other. And [former San Francisco Supervisor] Bevan Dufty, whose father was married to Gloria Swanson, told a funny story about Swanson.

CHITTICK My favorite times were when I would walk up the side of the auditorium and just watch the people watching it. And it was because all the work was done, and it was going on, and they were just enjoying it. People would be laughing, or whatever, all their faces turned up to the screen.