“No other crime thriller compares to Filibus!” trumpeted a double-page ad in the April 1915 edition of Italian film magazine La Vita Cinematografica. For once, studio PR was no exaggeration. Filibus, which follows the exploits of a futuristic female super-villain who pounces on her prey from a zeppelin manned by a crew of loyal henchman, is one of a kind. “Who is Filibus?” asks the ad. Contemporary viewers might also wonder how this cross-dressing antiheroine, heralded by some as cinema’s first lesbian, managed to emerge from an Italian cinema dominated by swooning divas and historical epics.

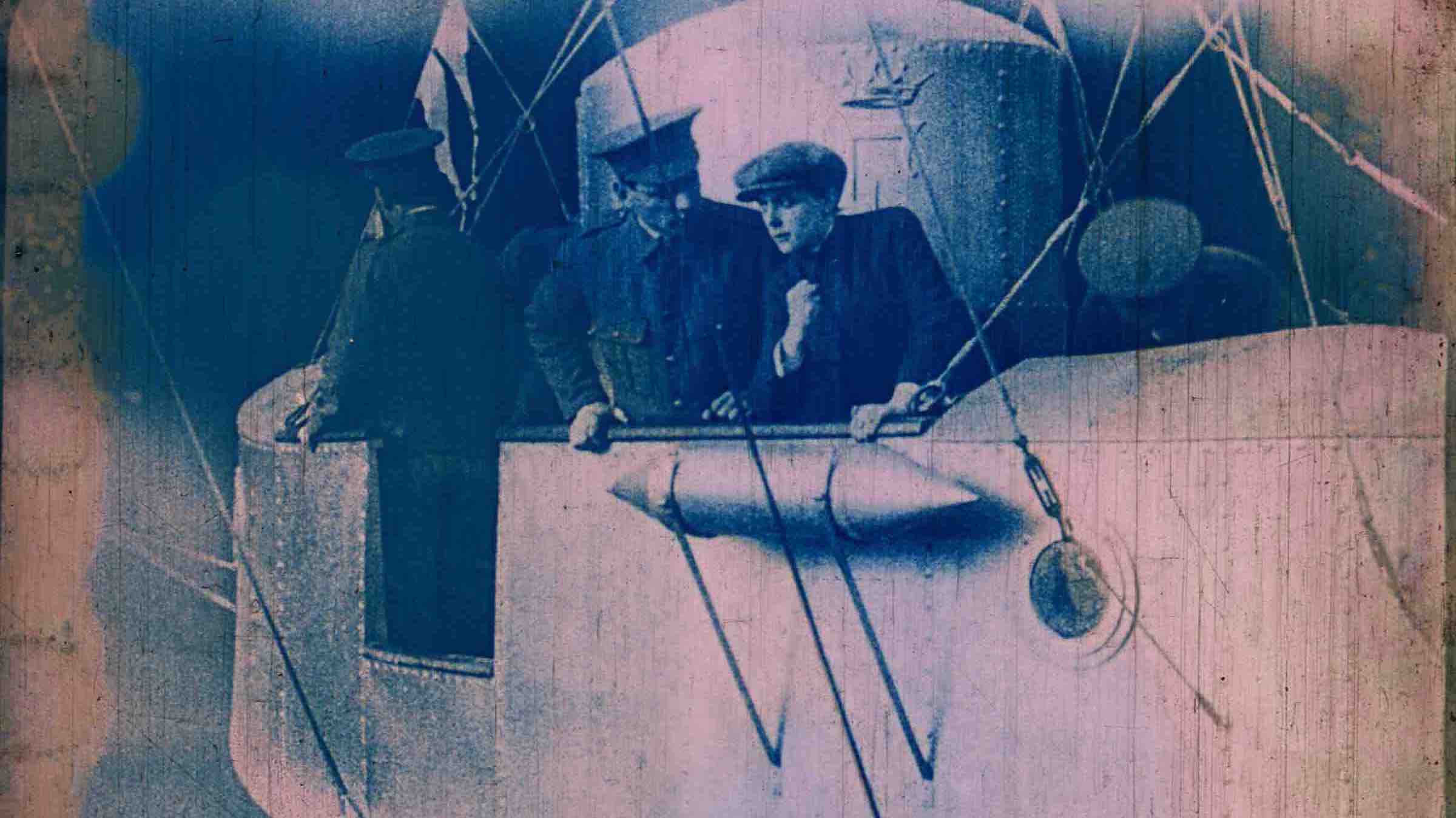

In the course of the serial’s five episodes Filibus plays cat-and-mouse with the great Detective Hardy, pocketing some diamonds along the way. The film is a precursor to today’s gadget-driven techno-thrillers: in her various schemes Filibus employs not only her zeppelin but something called a heliograph, a tiny camera, a miniature gun, lots of soporific drugs, and a fake handprint. She commutes between zeppelin and terra firma in a kind of tin can (complete with phone), which Detective Hardy fails to notice, even when it’s hovering over his terrace. The special effects are endearingly low-budget, but who cares, when the action is fast-paced and just plain fun?

Like any self-respecting super-villain, Filibus is a mistress of disguise, posing as the Baroness Troixmonde for a visit to the detective and later insinuating herself into his household camouflaged as the aristocratic dandy Count de la Brive. This male impersonation was part of what film historian Angela Dalle Vacche describes as a widespread questioning of gender identity that, at the time, “was at the very center of Italy’s modern daily life.” Divas and socialites went to Futurist parties wearing “jupe-culottes,” and Francesca Bertini played the male lead in 1914’s L’Histoire d’un Pierrot (directed by Baldassarre Negroni). Filibus’s trim suit and newsboy cap give gender boundaries a fairly forceful push compared to the jupes-culottes (a pants-skirt hybrid); but still more radical is the way the film destabilizes appearances in general, constantly oscillating between reality and illusion, whether it’s diamonds, kidnappings, or wardrobe until it seems that all of life is one big masquerade. When Filibus, disguised as the Count, takes the detective’s sister for an evening stroll, it’s anybody’s guess whether the flirtation is opportunistic, genuine, or a combination of the two. Filibus bamboozles Hardy so thoroughly that he questions the evidence of his own senses, and even his sanity.

The obvious model for Filibus is Louis Feuillade’s popular crime serials Fantômas (1913–1914). Contemporary reviewer Monsù Travet noted the pilfering “from certain detective masterpieces of French writers” in his 1915 review, concluding: “I would hate to see the director of Filibus sued for literary plagiarism.” Filibus copies Fantômas’s mask and use of multiple disguises, but as a modern-day reviewer for the online journal Á Voir à lire notes, while she may be as intrepid as her French cousins, “her character is prankish rather than genuinely malevolent.” An even more pertinent predecessor, given its female protagonist, is Victorin Jasset’s Protéa (1913). Protéa is a kind of super-spy, chasing after a secret treaty (in the run-up to World War I spies and double agents began to proliferate on European screens). The opening credits introduce Protéa’s various covers—including a male soldier—in a series of dissolves similar to the introduction of Filibus’s alternate personas at the beginning of Filibus. However, there are important differences between the two. Filibus has no Charlie’s Angels-type boss to call the shots and, where Protéa shares screen time with her male sidekick known as the Eel, Filibus is flanked by interchangeable male minions. Even more interesting, Protéa may disguise herself as a man, but when answering the telephone at home she’s dressed in skirt and blouse. In contrast, Filibus suggests that the Baroness’s skirts and ostrich-trimmed hat are as much a disguise as the Count’s evening clothes and monocle. Lounging on the zeppelin pondering her dastardly schemes, Filibus prefers her suit and cap.

While Filibus was flying over Italy in 1915, the women below were lagging behind their western European sisters when it came to civil rights. Married women couldn’t get divorced, they couldn’t inherit property, or even subscribe to a newspaper without their husband’s authorization, according to Dalle Vacche. Diva film melodramas depicting women driven out of their homes, losing custody of their children, shamed and suffering, were a gaudy reflection of this reality. But as Dalle Vacche points out, lower profile, action-oriented shorts like Nelly la Domatrice (Nelly the Lion-Tamer, 1912) and La Poliziotta (The Policewoman, 1913) suggest another facet of female experience. If the diva genre reflected Italy’s victimization of women, then these short action films of women in charge reflected a new vision of female autonomy.

Cristina Ruspoli, who plays Filibus, starred in some of these action-women shorts, but information on the actress, as well as the rest of the film’s cast and crew, is scant. From 1912 to 1916, Ruspoli accumulated some thirty credits, including a few big-budget historical epics typical of Italian cinema in the 1910s, like Salambo (1914). Producer Corona Films had an equally short run; the Turin-based company made about twenty-six films between 1914 and 1918, “for the most part adventure and small time features interpreted by second-rate actors,” according to Cinema Ritrovato’s 1997 festival program notes. Actor and director Mario Roncoroni had a longer, more eclectic career, codirecting La Nave (1921) with poet Gabriele d’Annunzio and then moving to Spain, where he continued to make films through the late 1920s.

An investigation into scenario writer Giovanni Bertinetti yields intriguing fodder for speculation on Filibus’s origins. In addition to his film work, Bertinetti wrote children’s adventure stories featuring the gadgets and science-fiction fantasy elements that animate Filibus. Film historian Silvio Alovisio places him as part of Turin’s intellectual circles, then abuzz with the Futurist ideas that Filippo Marinetti proclaimed in his 1909 manifesto: a love of technology and speed, a belief in the cleansing power of war and violence, a disdain for the past, and call to destroy museums and libraries. Marinetti might have been describing Filibus herself when he wrote, “the essential elements of our poetry will be courage, audacity and revolt.”

Futurism also called for the destruction of feminism, which complicates its connection to Filibus. It’s worth noting, however, that some women embraced Marinetti’s philosophy and tried to resolve the contradiction. Valentine de Saint-Point released the Manifesto of Futurist Women in 1912, rejecting Marinetti’s concept of superior man and inferior women (“It is absurd to divide humanity into men and women. It is composed only of femininity and masculinity.”) while echoing the Futurist call for an infusion of virility “lacking in women as in men.”

Here’s where Futurism begins to merge with the Italian craze for physical exercise, championed by Turin-based physiologist Angelo Mosso. Mosso, author of La Fatica (“Fatigue”), argued for gymnastics in schools and specifically referred to women when he told a group of educators, “We must stop them on the downward and fatal slide toward hysteria.” Italy, like its divas, was enervated, languid, and in need of toughening up; strengthening on the individual level, Mosso suggested, would lead to a stronger civic body.

Scriptwriter Bertinetti seems to have agreed with Mosso. In addition to films and novels, he also wrote self-improvement books like Il Mondo è tuo (“The World Is Yours,” 1907) under the pseudonym Ellick Morn as well as an essay in 1918 for La Vita Cinematografica, “Il Cinema. Scuola di voluntà e di energie” (“Cinema: School of Willpower and Energy”), in which he argues for cinema’s power to “solicit even the most passive individuals to act by imitating the deeds and actions projected on the screen.” Was Filibus possibly conceived as an inducement to the droopy divas to pull themselves off their chaise longues?

Although the final frames of Filibus hint at a sequel, it was not to be. A few months after the film was released, Italy declared war on Austro-Hungary and Italian film production dropped precipitously over the next few years—possibly explaining why Cristina Ruspoli’s credits seem to stop in 1916, why Corona Films went out of business, and why Mario Roncoroni moved to Spain. By rights, a film as minor as Filibus should have vanished from history as quickly as its creators. That it has survived for us to watch, analyze, and marvel at is a small miracle.

Presented at SFSFF 2017 with live music by Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra