However neglected, perhaps correctly, the history of independent exploitation films is as long as any other varietal of film—the nudie, the sensational barnstormer, the adults-only “if you dare” faux-exposé have always been with us. How we might approach this kind of film, beyond any sort of second-hand salaciousness or so-bad-it’s-good fanboy weirdness, remains an open question: what, exactly, are they good for? Plenty, actually, if we’re talking about purportedly educational documentaries like André Roosevelt and Armand Denis’s Goona Goona, which reveals in graphic terms certain details of two separate cultures. The first, right on the surface, is Bali’s society of the 1920s and early 1930s, weathering but seemingly unfazed by Dutch colonization, and still in a state largely uncorrupted by the tourism that arrived thanks to popular reports by visiting anthropologists like Margaret Mead, and to sensationalizing films like Goona Goona. Since Balinese daily life entailed ubiquitous female nudity—bare breasts—we also get a taste of a second culture, America in the early ’30s, a naïve but restless middle-class heartland of narrow-minded churchgoers and (publicly) monogamous small-towners, modest immigrants and buttoned-down Everymen to whom a stag reel would be a freakish object, and for whom a film filled with casual tropical nudity represents a tantalizing demi-pornographic itch that they could not scratch in any other way.

That might be the most educational aspect of a film like Goona Goona—that it reveals an America so sheltered and limited in its experience that the film’s utterly chaste visions of lovely Balinese flesh exploded in their heads as if a gloriously taboo gift from Satan. Not that Roosevelt and Denis’s cobbled-up little movie can’t often seem sexy; the male and female pulchritude on view is uniformly toned and young and unabashed (except when it is, on occasion, flabby and aged and unabashed). But the difference between 1932 and 2019, in terms of semi-illicit sex media, is like the difference between the telegraph and FaceTime. It’s a truism we know in our bones, even if perhaps we weren’t aware of it back then: the less we had at our disposal, the more electrifyingly delicious it seemed. Possessing a sense of the covert naturally helped things (as opposed to being able to muster any sexual imagery, even that produced in 1932, on our laptops in microseconds). Sometimes, consuming exploitation required a sense of secret mission. In the early ’30s, barnstorming distributors like Dwain Esper and Kroger Babb (and the other so-called “Forty Thieves”) leased theaters on a night by night basis, or rented out a church basement or Elks Lodge for a short run, advertised and showed their film and then got out of Dodge before the church ladies could mobilize. Films like Goona Goona never had wide or even official releases; if you owned a print, you’d set up a screening yourself and pocket the proceeds, before moving on to the next town or city neighborhood under the shroud of night.

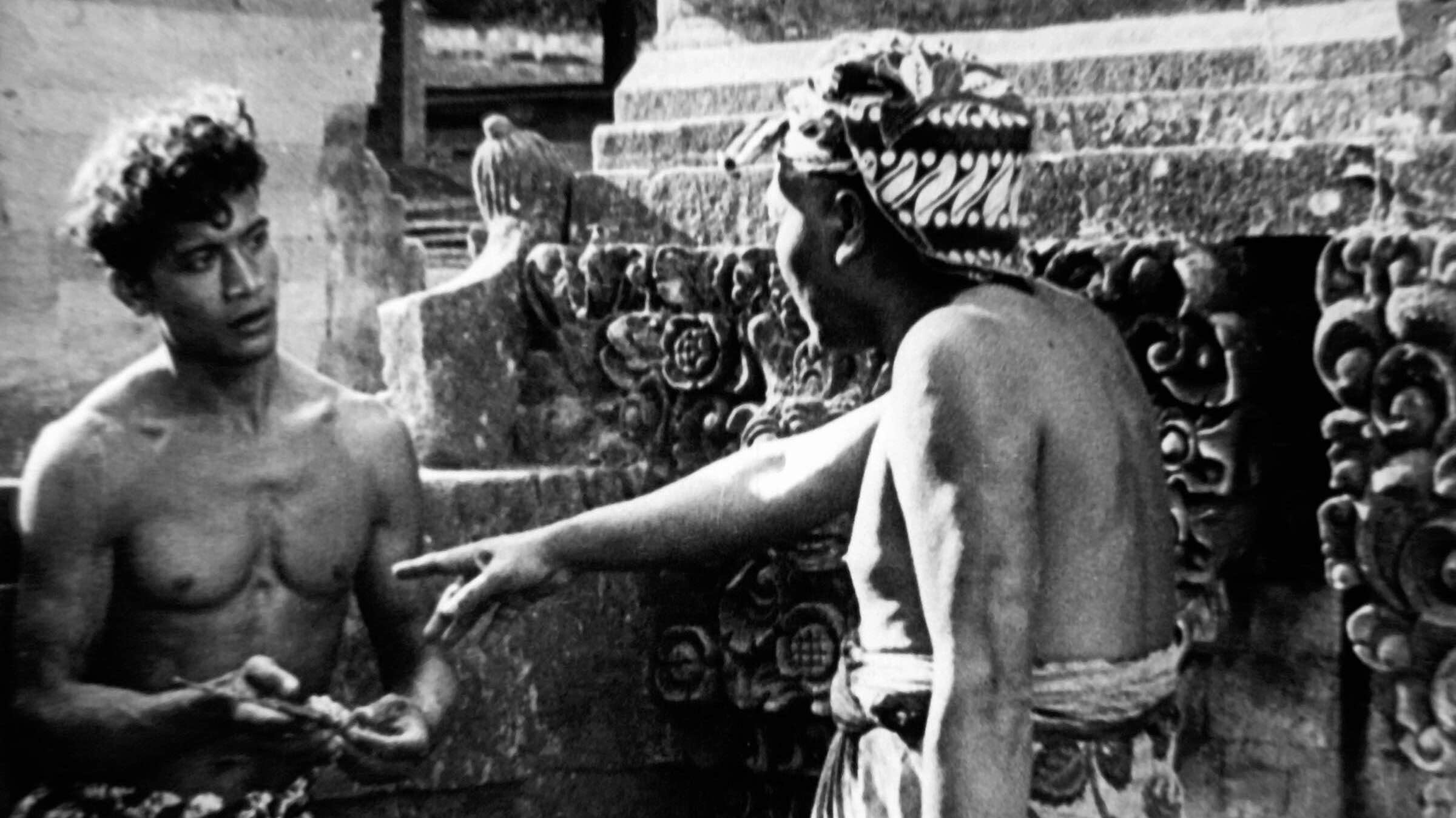

Roosevelt and Denis didn’t seem to have any other agenda in mind, if you take the film itself as Exhibit A. Their film is boldly exoticist, no-frills, quasi-informational, clumsily melodramatic, and most of all wide awake to naked womanhood (and girlhood, actually). Which is not to say it is entirely artless. Bali is beautifully photographable, after all, and the directors—Roosevelt, future director of Man Hunters of the Caribbean, and Denis of Frank Buck’s Wild Cargo and a series of safari films—sometimes display a deft eye toward dramatic framing. The film begins as a kind of explanatory travelogue about life in Bali, from a predictably “First World” perspective (the filmmakers were French and Belgian), before quickly segueing into an entirely fictional story about a tragic love triangle centered on a princess, the narrative of which is haphazardly relayed via title cards and narration (in the sound version). Still, as pressing as the story is at times, you’re never not thinking about the aw-shucks American schmoe for whom the lovely Balinese females might have been the only nude woman he’d ever seen beyond his wife.

That is, of course, unless the viewer in question was an aficionado of exploitation films, which though often advertised fleetingly and screened in unregulated circumstances, were rarely in short supply. Even movies about or featuring nude Balinese were numerous (most notorious among them was the nude-teenager-focused Virgins of Bali, also from 1932), and films cropped up with racy footage from Borneo, New Zealand, Hawaii, Fiji, Indochina, the Congo, and elsewhere. Nowhere was as frequented, though, as Bali, and one can only imagine what the Balinese thought as yet another gaggle of white men with cameras showed up on their shores, cornering the island’s topless maidens for yet another film shoot.

At least, in the grand tradition of travel documentaries that began with the Lumière actualities filmed in North Africa and the Middle East before the turn of the century, Goona Goona is all shot absolutely on location. (Many of the Forty Thieves’ releases were recycled archival footage, or reenactments shot on warehouse studio sets; one film that used footage shot in Cambodia, 1935’s Angkor, augmented itself with nude Hollywood prostitutes recruited from a Selma Avenue brothel.) Bali, as it’s preserved here on film, is its own glory, and the Balinese are relaxed, sweet, and, strangely, comfortable with and adept at movie acting—without, we presume, much exposure to the art form. (There are no signs of electricity in the film’s tribal life, much less any buildings that aren’t villagers’ huts or ancient temples.) You can scan for traces of Thai, Chinese, and Filipino culture in the Balinese traditions, but the island’s generalized air of breezy tropical pre-industrialization is, as you’d expect, the primary takeaway. And all those breasts? Almost predictably, halfway through the movie their constant exposure renders them unremarkable and untantalizing, just as they are, apparently, to the Balinese themselves.

One can hardly avoid indexing Flaherty and Murnau’s Tabu (1931), another tropical idyll that morphed from quasi-doc to outright romantic fiction, but no one has ever called Tabu exploitation, or even very orientalist, probably because of the respectful and poetic sensibility Murnau brought to life in Tahiti. Roosevelt and Denis, on the other hand, who were expressly taking advantage of censorship laws stating, for anthropological reasons, that “native” nudity would not be outlawed, and thus helping to establish a disreputable subgenre of sexploitation that sold so many tickets in the 1930s that the Hollywood industry and press gave the films the moniker “goona-goona epics.” (Denis recounts in his memoir being “appalled” at all the crass ballyhoo surrounding the film’s Times Square premiere—Goona Goona sundaes featuring two scoops of chocolate ice cream each topped with a maraschino cherry, for one—but also relished what it meant for his career: “I knew I had finally had arrived.”) Money could be made by recutting and rereleasing such films, sometimes combining their footage and presenting it as something new. Typically, Goona Goona has had many titles, a vast variety of redubbed narrations and lost or added title cards, and an unknowable number of running times. The rumored original length of seventy minutes is lost, though the current restoration is certainly an improvement, at least from a historical perspective, over a forty-eight-minute 1942 release. Perhaps for most of us sixty-six minutes is more than enough.

Even as the 1930s ended, the phenomenon of gonna-goona epics continued unabated, driven only a few more feet underground by the Production Code through the ’40s and ’50s, exploiting the aggregation of social liberalism and eventually morphing into if-you-dare objects like Mondo Cane (1962). Only our increasing familiarity with real pornography and the postwar reality of “Third World” peoples and their cultures breaking free of colonialism slowly made the subgenre more or less obsolete. Ethnography and exploitation turned into the more responsible “witness.” As scholars have been finding in the last few decades, discovering and documenting this previously reviled and forgotten leg of film history limns a kind of secret history of the 20th century, a portrait of an America compensating for its own conservative norms and imperial engagement with the world by seeking out subversion where in fact there is none—or, perhaps, by converting the world’s pre-industrialized peoples into sexualized objects as a last, desperate effort to retain a sense of hegemony.

Presented at SFSFF 2019 with live music by Club Foot Gamelan

Club Foot Gamelan

Last heard at the festival in 2013 with Henry de la Falaise’s Legong: Dance of the Virgins (1935), also filmed in Bali, Club Foot Gamelan combines the talents of two Bay Area ensembles, Gamelan Sekar Jaya and Club Foot Orchestra, to accompany Goona Goona: An Authentic Melodrama of the Isle of Bali. Now celebrating its 40th anniversary, the Balinese-style Gamelan Sekar Jaya is currently under the direction of guest musician I Nyoman Windha, widely regarded as Bali’s greatest living composer and the recipient of numerous international awards. Club Foot Orchestra has composed and performed for silent film since the 1980s. Together they will play a score by Club Foot Orchestra’s Richard Marriott, who also conducts.

Sekar Jaya: I Nyoman Windha (gamelan, voice), I Dewa Berata (gamelan, voice), Marianna Cherry (gamelan), Carla Fabrizio (gamelan, cello), Samuel Wantman (gamelan), Sarah Willner (gamelan, viola)

Club Foot Orchestra: Alisa Rose (violin), Beth Custer (clarinet), Chris Grady (trumpet), Richard Marriott (winds, conductor