It is not surprising that D. W. Griffith set some of the great scenes in The Birth of a Nation during the Civil War, given his next project. Interested in conflicts that tear at the fabric of society, Griffith fought a battle within himself that pitted his vision, his talents and his nagging doubts against each other to produce one of the great movie phenomena of all time: Intolerance. He released it in 1916 and struggled with its financial burden and its disappointing popular reception for the remainder of his career. Intolerance was not, however, the ruinous career-ending venture it is reputed to be – indeed, it was following Intolerance that Griffith made Broken Blossoms (1919) and Way Down East (1920), two of his most successful and popular films. Certainly Griffith never lived to see his colossal movie ensconced as an artistic landmark, considered by many as among the most influential films ever made. There is, however, little doubt that he had fun making it. Interweaving four historical epochs over three hours in a non-linear feast of cross-cutting (there are more than 50 transitional edits between the four plot lines), Intolerance was a radically new film that, despite ultimately leaving some viewers confused by Lilian Gish and her rocking cradle, opened the world’s eyes to the power of an emerging and increasingly complex cinematic grammar and technique.

While Intolerance was meant to be an epic blockbuster, it had comparatively humble origins. As was his tendency, Griffith began work on an entirely new film while still wrapping up The Birth of a Nation. This new film, The Mother and the Law, was far from a historical epic, concerning as it does the contemporary plight of a young couple torn apart by injustice amidst a tense and desperate labor strike. Unlike The Birth of a Nation, it did not cry out for elaborate costumes, battles scenes or historical figures. Yet, by the time it was concluded, The Mother and the Law had metamorphosed into Intolerance; a hail of images that sweep from the fall of Babylon to the massacre on St. Bartholomew’s Day, from Christ’s crucifixion to a modern-day public execution. As the enigmatic Griffith left little in the way of a definitive statement to explain why his modest six-reeler The Mother and the Law became the reeling fourteen-reeler Intolerance, many critics have had to look to the particular characteristics of the man behind it, in order to gain insight.

David Llewelyn Wark Griffith was born on January 22, 1875 near La Grange, Kentucky to Mary Oglesby and “Roaring Jake” Griffith, a local hero who had achieved fame as a Confederate Colonel and later as a delegate to the Kentucky Legislature. His father’s death in 1885 deprived Griffith and his family of their money and privilege, forcing them to move to Louisville. It was here that David Wark discovered the theater, and he began to alternate odd jobs with attempts at playwriting and acting. Finding success elusive in the traditional theater, Griffith gravitated to the burgeoning movie business in New York City, where he was given abundant opportunities to act, write and eventually direct. Between 1908 and 1913, Griffith was the driving force behind the Biograph Company, where he made in excess of 450 films, many of which refined fundamental camera and editing techniques. It was also at Biograph that Griffith met many of the people with whom he would collaborate for his entire career as a director, most notably cameraman Billy Bitzer. In 1914, frustrated with Biograph’s tepid response to his feature-length period narrative Judith of Bethulia, Griffith left to form his own production company, and he immediately began work on The Clansmen, or The Birth of a Nation.

If the multiple million-dollar success of The Birth of a Nation gave Griffith the reputation and financial resources to do whatever he pleased in its wake, the enormity of the response and the ardency of the backlash to its controversial theme complicated his subsequent projects. Remarking on the film in 1915, Francis Hackett of the New Republic called it “spiritual assassination,” and the April 6th New York Globe referred to Griffith as “willing to pander to depraved tastes and to foment a race antipathy that is the most sinister and dangerous feature of American life.” Griffith himself vehemently defended it as a tribute to American history and a homage to the bygone Southern culture that had haunted him ever since his family’s fall from privilege. Confronted with the film’s overt racism, few viewers today can disagree with either Mr. Hackett or the New York Globe. However, the Evening Mail observed that the film’s New York premiere “swept sophisticated audiences like prairie fire,” and theaters across the country were filled for months. Amidst this outpouring of enthusiasm, the relatively humble and mostly-precedented The Mother and the Law must have appeared very small to Griffith, and the same expansive imagination and drive to innovate that had spurred him throughout his career now compelled him to outdo himself.

The first to go was a linear plot line. In place of the chronological structure of The Birth of a Nation or Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914) – a source of inspiration—Griffith undertook an arching historical sweep that found its common thread in an ideologically driven theme. He had previously cut multiple story lines together around a single theme in A Corner in Wheat (1909) and Home, Sweet Home (1914). This time, Griffith’s theme was intolerance or, specifically, society’s tendency to restrict and defile human freedom, love and honor. In part a thinly-veiled indictment of those who criticized The Birth of a Nation, in part a continued response to the perceived loss of Southern pride and personal dignity, and in part a loose framework upon which to make a single behemoth out of four separate films, Intolerance has few equals in film history for its sheer resourcefulness and audacity of vision.

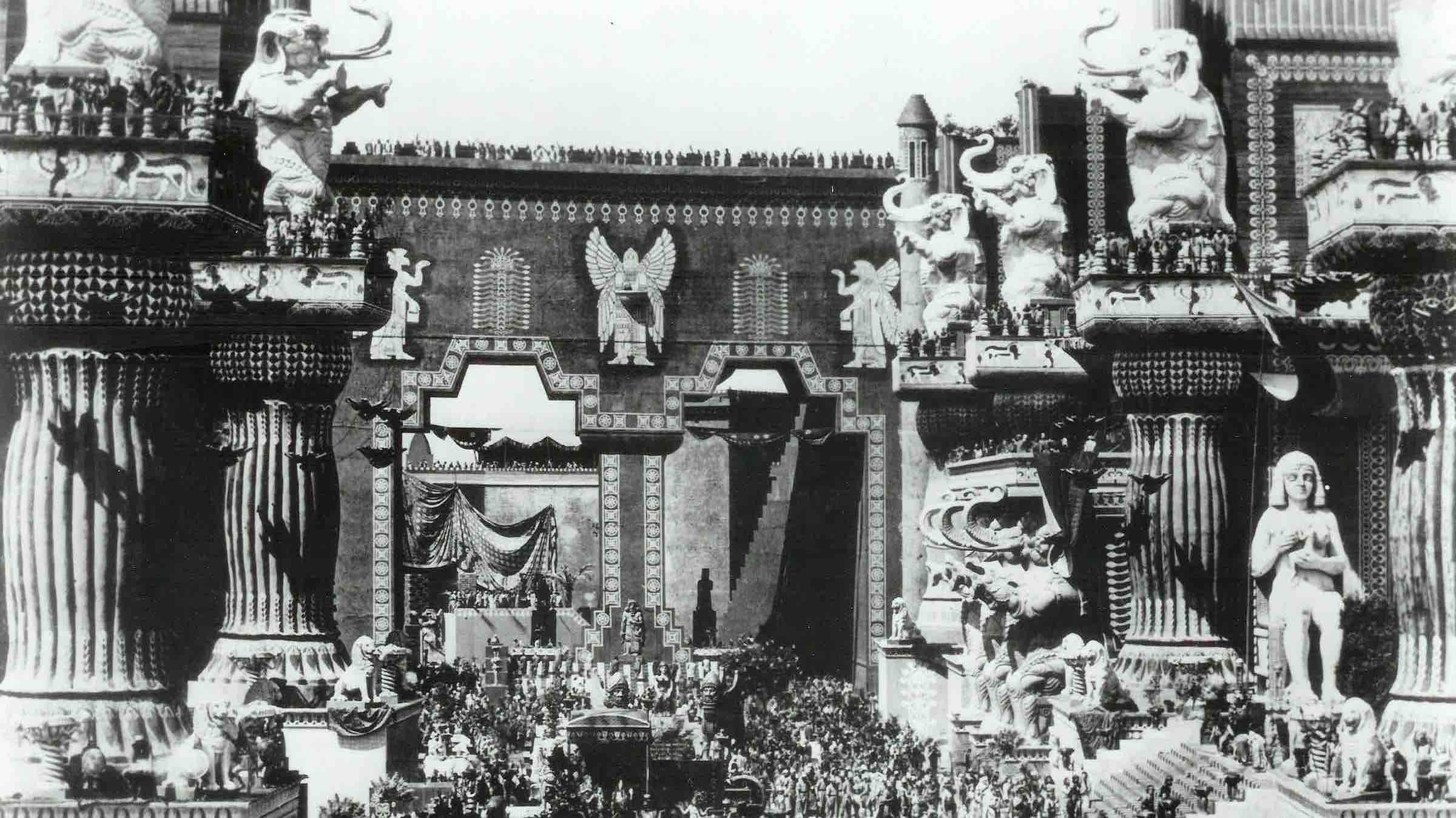

Engaging himself in a contentious struggle to make the world’s largest film, Griffith continued to work, as he always had, without any script. Only a handful of Griffith’s crew were even aware that a single film, and not four separate ones, was being made. As Griffith’s vision grew in scale, so too did the need for prodigious quantities of sculptors, assistant directors, elephant handlers, pyrotechnicians, and real estate. The French and Judean stories, lavish productions all by themselves, were thoroughly dominated in stature and detail by the Modern and Babylonian sequences. Construction grew to such a point that Griffith had Set Designer Walter L. Hall’s office built on high stilts, to afford him a better view of the increasingly expansive set. To film the Babylonian sequences, many thousands of extras were transported daily on streetcars out to the Domiguez Slough (itself pressed into duty as the Euphrates) to serve as the Persian Army. Bemused onlookers marveled at the walls of Babylon towering 160 feet high over Sunset Boulevard. Large dollies and cranes, along with platforms mounted on vehicles, allowed for radical filming techniques that thrilled audiences and cameramen alike.

Griffith ultimately found that his greatest challenge lay in the editing room. He assembled, took apart, and re-assembled the footage, as he fought to bring coherence to his vision. The critical reception that greeted the version he released in late 1916 was uncertain, as many viewers found the film to be spectacular but inscrutable. Daunted by the challenge of an authoritative, final edit, Griffith continued to cut and re-cut the film over the course of the next two decades: for foreign audiences, for revival screenings, for release of versions taken from the separate story lines. There remains no definitive copy of the film, and the 1989 reconstruction produced by the Museum of Modern Art in New York is itself the source of some critical controversy, as it contains roughly 20 minutes more footage than any version that Griffith himself ever exhibited. These issues, however, fade when placed beside the sheer kinesthetic power of the film, a power that continues to rock audiences today as forcefully as it did almost a century ago.

Presented at Silent Winter 2007 with live music by Dennis James on the Mighty Wurlitzer