In Max Linder’s final film, he indulged a common childhood fantasy. Expectations had been seeded in his childhood that he would grow up to take over the family business, a vineyard. However, he later wrote that “nothing was more distasteful to me than the thought of a life among the grapes.” What stirred his imagination as a boy was the thrill of performance. He was enthralled by the traveling big tops and theater companies that rolled into town on occasion. He especially enjoyed the lurid Grand Guignol shows at the annual festival. At the age of forty, in a film studio in Austria, Linder finally got the chance to run away and join the circus.

Shooting began on King of the Circus (Max, Der Zirkuskönig) at the Vita-Film studios in Vienna in December 1923. In the film, Linder plays a gadding young aristocrat who falls in love with a trapeze artist, but he won’t be able to win her hand in marriage until his mastery of circus skills rivals her own. He sets up an elaborate con so that he can impress the crowds with a daring act of circus bravery, but at the last minute, circumstances dictate that he has to do it for real. Comparisons are inevitable with Charlie Chaplin’s later film The Circus (1928)—substitute the Little Tramp for Linder’s tipsy count and the plots seem to share an abundance of DNA. The films are, however, very different in tone and action. Where these two big-top features bear comparison is in their behind-the-scenes friction and production delays. Chaplin’s centered on a very messy, public divorce, and Linder’s woes foreshadowed a grimmer fate.

Linder had married Ninette Peters in the summer, and she was already pregnant by the time the couple arrived in Vienna, a few days later than anticipated. Her pregnancy seemed to diffuse Linder’s angry displays of jealousy, but all was not well between them, nor at the studio. Toward the end of January 1924, a local newspaper reported that not a single frame of the film had been shot and that delays had been caused by Linder rejecting the apartment he had been supplied with for his stay, as well as refusing to work in a studio that was too cold (by one degree Celsius)—which may have been a requirement of his recovery from an accident one year previously. One more concrete detail was that the original director had a heart attack and returned to Paris, to be replaced by Édouard-Émile Violet. And then again there was a report of his costar Vilma Bánky being forced to repeat one action for multiple takes until her arms began to spasm. The reporter in question was forced to retract some of these claims, and the impression that Linder was deploying “chicanery” to delay the production, but there were more serious problems in the offing. On February 23, 1924, the press reported that Max and Ninette had attempted suicide via a joint overdose of barbiturates. Both parties survived after being taken to a local sanatorium for treatment, and the police seemed not to think the incident worthy of a report. Twenty months later, however, the couple died in eerily similar circumstances, at Linder’s hands, leaving their baby daughter Maud an orphan.

This, then, is Linder’s final completed feature film. His previous film had been something of a departure. Au Secours! (1924), directed by Abel Gance, is an oddity in many ways, not least because it is not an out-and-out comedy. This two-reeler is essentially a horror film with some comic and gruesome elements, featuring Linder as a newlywed who makes a bet that he can stay in a haunted house from 11 p.m. to midnight. This was the film Linder chose to make on his return to France after his second, somewhat deflating, stint in Hollywood.

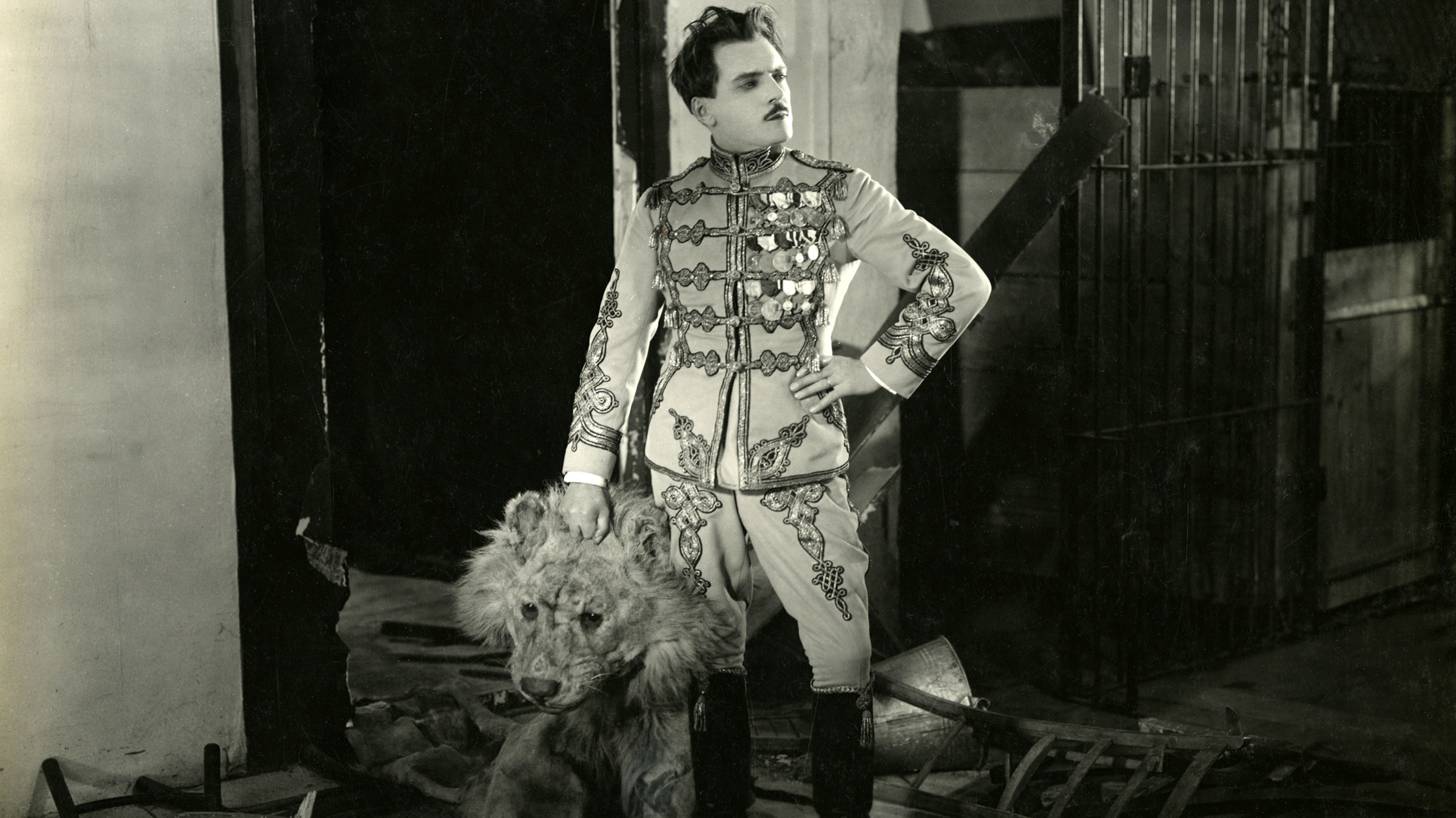

King of the Circus is a feature-length film that promises, and delivers, a much more straightforward scenario, with plenty of opportunities for Linder to flex his slapstick muscles and to inhabit the dapper “Max” persona that made him famous. Linder portrays playboy aristocrat Comte de Pompadour, the “dissipated nephew” of a strict guardian who insists that he settle down. The young count is a confirmed bachelor, or in his baffling choice of words, a “vegetarian,” and this frisky herbivore deploys subterfuge to sneak out for a party, which will lead us into our first extended comedy set-piece as Linder runs riot in a nightclub. The jokes often arrive at Pompadour’s expense. Even before he leaves the hotel he is stuck with a coat-hanger tucked into his dinner jacket and he will end the sequence sliding out of the same coat, which is hung up on a peg. The implication is clear, that Linder won’t get to play the debonair smoothie in this film. After a night of debauchery, Linder executes a very funny routine as a man too drunk and disoriented to get into bed, or even to hang his hat on the bedpost. The punchline for Pompadour is a gag we have been in on since the start—that’s not his bedroom but a display in a furniture store window. Pompadour awakes from his boozy slumbers to find a jeering crowd has assembled on the other side of the glass to watch him snore. Happily the humiliation is brief, as the count is still far too drunk to comprehend his predicament. Nevertheless, his discomfort with audiences, being in front of them, or part of them, emerge as a theme in the film.

The meet-cute with Bánky’s trapeze artist Ketty is one of Linder’s darker gags (and he was known for them). Struggling to choose between the three possible brides his uncle has chosen for him, Pompadour decides to aim his gun at their photographs and the first to fall will be his wife. Instead, he hits a live target, grazing Ketty’s arm with his bullet as she passes by. Once Pompadour’s romantic mission is established, the film settles into a more conventional comedy mode, with humorous highlights including Pompadour’s awkwardness among the crowd at the circus as he witnesses Ketty’s act, his mismanagement of a flea circus (an inadvertent act of revenge on the audience?), his interactions with a gaggle of overbearing clowns, and, best of all, his improvised circus-training camp in his hotel room. This last consists of rope, precariously balanced furniture, a stepladder, and the deft assistance of the count’s lanky valet. Each move is performed at high risk, and with deceptively little skill. It’s pure clowning, albeit without an audience. It’s offstage, too, that Pompadour performs his final trick, “defeating” the lion, earning the respect of the circus master and the right to woo the girl of his dreams. But he’ll take his bow in the limelight, applauded by the audience, who are finally, unequivocally on his side.

The film does end on a surprisingly quiet note, however, with the lovers alone in the circus ring, engrossed in each other’s company and letting the sawdust stream through their fingers, unaware that the audience has long since left the tent. The film seems to say that after Max’s moment of triumph, after the courtship and the wedding, life must go on, with two people passing time together in private. There’s a poignancy to this final scene that allows a moment of reflection, for the film itself, for Linder’s screen career, and for his marriage, viewed through the dubious benefit of hindsight. It’s an unexpected deep breath, after an hour of winningly elastic comedy, from one of the silent screen’s kings of slapstick.

Presented at SFSFF 2022 with live musical accompaniment by Philip Carli