FANTASMAGORIE (1908) Directed by Émile Cohl, HOW A MOSQUITO OPERATES (1912) Directed by Winsor McKay, ADAM RAISES CAIN (1922) Directed by Tony Sarg, AMATEUR NIGHT ON THE ARK (1923) Directed by Paul Terry, BED TIME(1923) Directed by Dave and Max Fleischer, FELIX GRABS HIS GRUB(1924) Directed by Pat Sullivan, A TRIP TO MARS (1924) Directed by Dave and Max Fleischer, VACATION(1924) Directed by Dave and Max Fleischer, ALICE’S BALLOON RACE (1926) Directedby Walt Disney, FELIX THE CAT INSURE-LOCKED HOMES (1928) Directed by Pat Sullivan

Is there a more reliable show-stopper than wedding animated cartoons to live-action footage? Whether it’s Jerry the Mouse swapping his usual feline foil for Gene Kelly in Anchors Aweigh (1945), Dick Van Dyke teaching a quartet of penguins how to shimmy in Mary Poppins (1964), or Bob Hoskins surviving a dark night of the soul in Toontown in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), these moments leave even the most seasoned viewers gaping like kids at a magician’s tent. We see the trick unfurl before our eyes, but wemarvel at the timing,the coordination, the consummate skill and confidence that sends a flesh-and-blood man dancing beside an ink-and-paint mouse.

The great revelation of the animated films of the silent era is two-fold: that cartoons and live-action were blended together from the very beginning of the medium and that this free mingling of skinand ink was the norm, not the exception. Over and over again, the cartoon cannot be separated from the cartoonist. Indeed, the cartoonist himself is often the star!

A direct line can be drawn between the early animated cartoons on the motion picture screen and the cartoons, caricatures, and illustrations that flooded newspapers and magazines at the turn of the 20th century. Not only did many pioneer animators gettheir start in print, their motion picture cartoons explicitly connected the new medium to its predecessors. Winsor McCay was already famous as a stage performer and creator of the Little Nemo in Slumberland newspaper comic strip when he made Gertie the Dinosaur (1914)—a hybrid film wherein McCay appears as himself in a long prologue, visiting the American Museum of Natural History and accepting a bet from another cartoonist that he “can make the Dinosaurus live again by a series of hand-drawn cartoons.” The main attraction—the animated portion where McCay makes good on the bet—is a quicksilver boast, a feat of derring-do, cartooning as performance. There’s a similar show-off air in McCay’s The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918), with the animator challenging himself to an astonishing degree of fidelity to detail in an act of cartoon reportage. An introductory sequence was also origi- nally part of McCay’s How a Mosquito Operates (1912), but in the version that comes down to us now, the six thousand individual drawings must stand on their own—which they do, in increasingly creative and excruciating detail, a new frontier in sicko realism.

Not all early cartoons were so literal. A more free-flowing, surrealist sensibility pervades Émile Cohl’s Fantasmagorie (1908). It begins with a live-action hand sketching a few white lines on a black backdrop. The drawings themselves are simple and child-like, but the myriad ways that one drawing drifts, transforms, or deranges itself into the next remains dizzying and destabilizing. It’s particularly astonishing to consider Cohl’s cartoon in the context of itscontemporaries. To look at live-action film history landmarks from the same decade such as The Life of an American Fireman (1903), Rescued by Rover (1905), or The Lonely Villa (1909) is to glimpse filmmakers cautiously, painstakingly groping their way toward a working grammar of space and time, taking the audience by the hand and guiding them between each new scene. Continuity is a pattern that can be recognized and deciphered: first we’re here, then we go over there, and then we go back where we started. Fantasmagorie has no patience for that exercise and uses its blank screen as a conjurer’s canvas; you blink and a flower has turned into an elephant, but before you puzzle that out, the elephant has been replacedby a build- ing. At one point, Cohl paints himself into a corner, and the cartoonist’s hand comes back to rearrange the pieces again. As with McCay, Cohl never asks us to suspend our disbelief, we’re always aware that the thing we’re watching is the product of a pen.

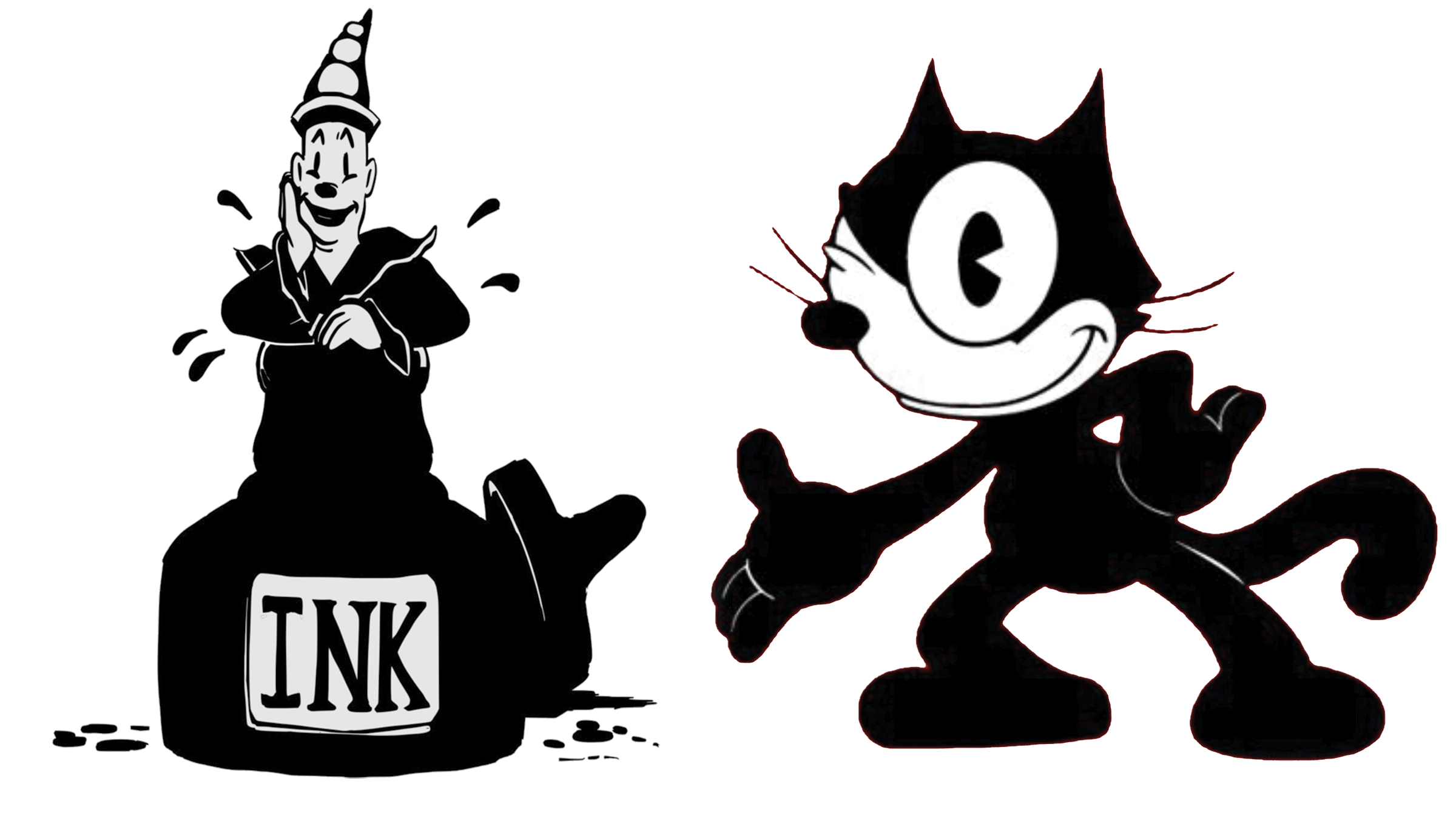

The cartoonist is never more central than in the superlative Out of the Inkwell series from the brothers Max and Dave Fleischer. Each short begins with Max summoning Koko the Clown from his inkwell and committing him to paper, granting the cartoon some conditional freedomuntil it’s time to stuff him back in the bottle. Often, as in Bed Time (1923) and A Trip to Mars (1924), Koko rebels and turns Max’s pen right back at him, treating the real world as pliable and plastic as the cartoon realm. The endless invention of the Inkwell shorts could be an essay unto itself, so let us only observe here how Koko may be the main attraction but only because Max plays straight man and second fiddle, a self-deprecating schlemiel often bested by his own creation. Max isn’t a world-beater and gentleman draftsman like McCay, but just a schlub trying to get through the workday without an ink stain in the eye.

There’s a more harmonious relationship between the human and the cartoon in Walt Disney’s Alice Comedies. The shorts series began in 1923 with Alice’s Wonderland, but the concept bore only a faint connection to Lewis Carroll—just a girl tossed into a wacky land without explana- tion or preamble. In animation genealogy, the Alice Comedies are first cousins to funny animal cartoons like Paul Terry’s Aesop’s Fables or the barnyard hijinks that Disney perfected in the 1930s. Often the live-action Alice is simply another character in an elaborate cartoon world with so much action bouncing around its frames that she sometimes seems like a supporting player in her own series—the supreme technical feat made to look effortless and mundane.

It’s not unreasonable to conclude on the basis of a short like Alice’s Balloon Race (1926) that the star of the series is not Alice, but Julius, a wily black cat who bears a striking—and not remotely coincidental—resemblance to Felix the Cat, the most famous cartoon character of the silent era. (Disney won a contract for the Alice Comedies after independent cartoon specialist Margaret Winkler lost the distribution rights to Felix and Out of the Inkwell; Winkler took a real chance on the unknown Kansas City animator, but clearly pushed Disney to give her another Felix.)

Felix began as a creature of film and quickly spawned a comic strip and an array of licensed merchandise. The Felix cartoons carried thename of putative creator Pat Sullivan, but the character was bigger than any interloping mortal; his cartoons didn’t begin with Sullivan (or Otto Messmer, who actually did most of the animation) sitting at a desk, puzzling out that week’s installment. Neverthe- less the Felix cartoons often relied on cartoon logic every bit as clever and playful as Fleischer’s or Cohl’s. In Felix Grabs His Grub (1924), Felix wonders how he’ll find something to eat—and then proceeds to climb atop the question mark that forms above his head to reach higher ground. In Sure-Locked Homes (1928), nighttime arrives as a series of ink blots falling from the top of the frame, as if dripping carelessly from an invisible cartoonist’s pen.

The profundity of Felix often sneaks up on you. Late in Sure-Locked Homes, Felix discovers that the mysterious figures that have been stalking him are only shadow puppets (much less delicately rendered but no less evocative than Tony Sarg’s marionettes, also part of the program). In that moment, we chuckle at one breed of animation scared near-to-death by another. On the page, it sounds self-reflexive and pretentious, but on screen it just works. That’s the trick of silent animation—big ideas rendered in invisible ink.

Presented at A Day of Silents 2023 with live musical accompaniment by Wayne Barker and Nicholas White