FILMS

Trolley Troubles; Oh, Teacher; Great Guns; Mechanical Cow; All Wet; The Ocean Hop; Bright Lights; Oh What a Knight

Created and Produced by Walt Disney, Ub Iwerks, 1927–1928

Donald, Goofy, Pluto, and… Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. That’s how the list of major Disney animated characters might read had certain events in the late 1920s unfolded differently, forever altering the history of animated film.

In 1923, Walt Disney headed for California with the hopes of getting into the movie business. He had had initial success in Kansas City, Missouri, making animated shorts for a local ad agency and later for his own “Laugh-O-Gram” studios. Fatefully, Disney accepted an $11,000 contract with Pictorial Clubs Inc. to produce six shorts. The company went bankrupt before fully paying Disney, forcing him out of business.

At the time, New York City was still the capital of animation, home to the studios that produced popular animation like the Felix the Cat and Krazy Kat series. Undeterred, Disney opted for California, as his brother Roy was already there convalescing from a bout of tuberculosis. In mid-1923, with a reported $40 in his pocket, Disney left for Hollywood.

Prior to leaving, Disney made one last short, Alice’s Wonderland (1923). Alice was inspired by Max Fleischer’s Out of the Inkwell series, featuring an animated Koko the Clown cavorting in a live-action world. Disney’s Alice cleverly switched that premise, putting a live-action girl in an animated world.

Margaret Winkler, distributor of the Felix the Cat series, saw Alice’s Wonderland and approached Disney to produce more. He had to scramble. He had no staff, and Winkler wanted the same child actress, Virginia Davis, to play Alice. Always persuasive, Disney convinced Davis’s family as well as animators Hugh Harman, Rudolph Ising, and Ub Iwerks to leave Kansas City for California.

The Alice series was popular with critics and audiences alike, but by 1927 the novelty of a live-action girl in a cartoon world had worn off. Smartly, Disney shifted focus from Alice to the cartoon characters, notably her sidekick Julius the Cat. Concurrently, Winkler’s new husband Charles Mintz had taken over her business, and Universal Pictures tapped him to get them back in the animation business. Universal, feeling there were already enough cartoon cats, suggested a series starring a rabbit.

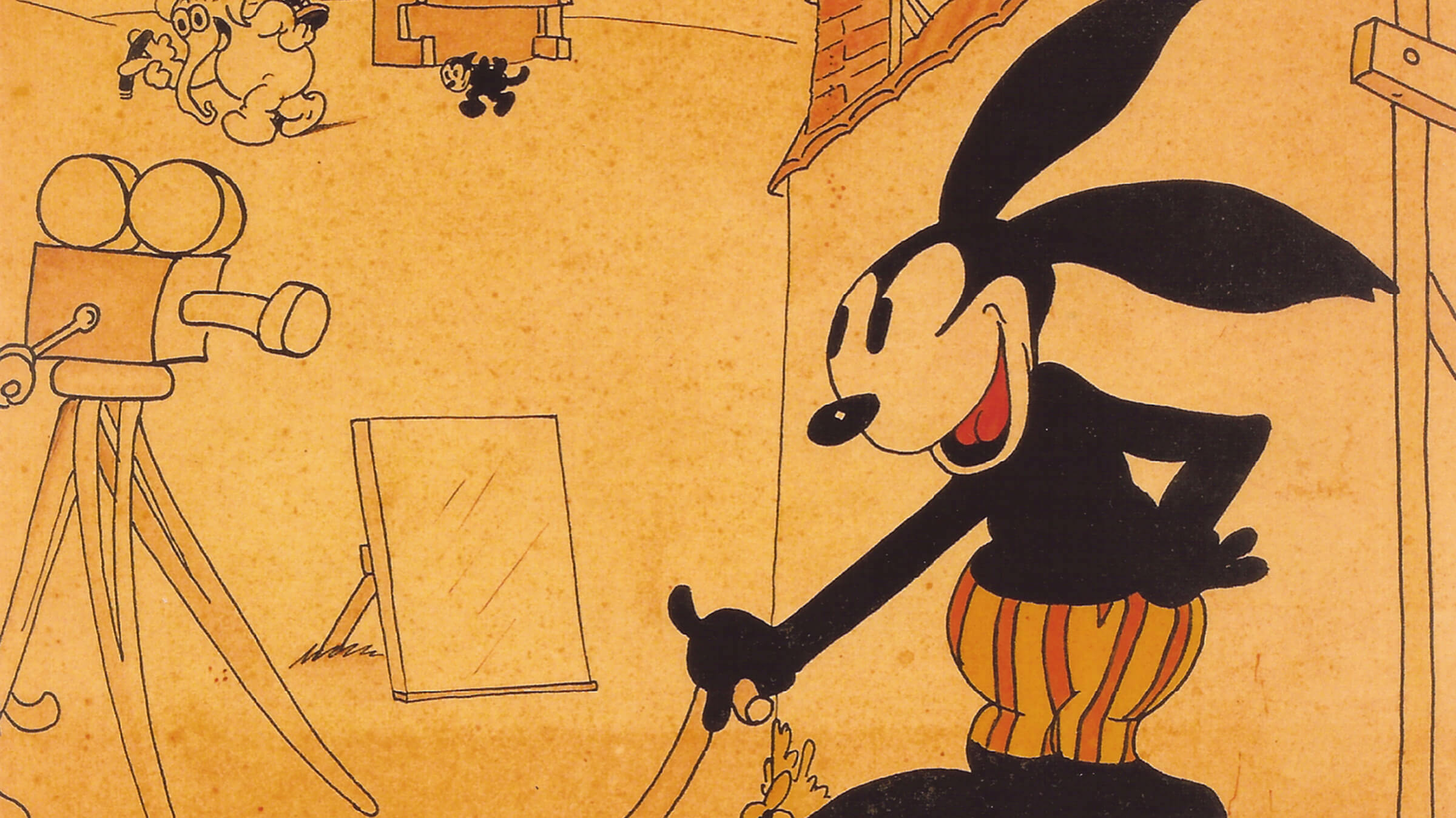

Disney and his best animator Ub Iwerks reworked Alice’s Julius into a rabbit named Oswald for Poor Papa (1927). After Universal executives complained that Oswald looked “too old,” Iwerks redesigned him to look younger for the second short, Trolley Troubles (1927). It became the first of 26 Oswald shorts created by Disney’s studio for producer Mintz and distributor Universal.

Disney was an expert storyteller and instinctively knew the shorts would be more successful if Oswald was more than a bystander. Instead, the humor arose from situations created for Oswald’s world and his reactions to them. The quality of the animation was also superior to the work of other studios, mostly because of Iwerks’s technical expertise and his skill at drawing perspective.

Disney and Iwerks developed an assembly-line system that met Disney’s desire for top-quality animation, story, and character development as well as allowing them to churn out one film every two weeks, as mandated by their contract with Mintz and Universal. Through Oswald, Disney also realized the potential for character merchandising. From the outset, Universal had promoted Oswald “tie-in” products, the first being an Oswald the Lucky Rabbit chocolate bar that hit the shelves in 1927.

Merchandise tie-ins, of course, were lucrative only to copyright holders. By early 1928, with Oswald on a roll, Disney felt confident enough to travel to New York to request an increase from $2,250 to $2,500 per short. Before he left, Iwerks alerted him that Mintz was signing Disney’s animators to new contracts, replacing Disney as their boss. Disney didn’t believe it until he arrived in New York, where Mintz offered $500 less per short, plus 50 percent of any profits. Mintz offered Disney, who thought of himself as Oswald’s owner, a contract to join Mintz’s firm as an employee. Disney learned that Universal controlled the copyright to Oswald and all profits from the character, regardless of who made the films. Feeling betrayed, Disney turned down Mintz’s offer and vowed never again to relinquish control of any of his studio’s creations. Before leaving New York, Disney wired his brother Roy to sign Iwerks, his best animator—and one of the few who refused to sign with Mintz—to an exclusive contract.

Iwerks’s contribution to Disney’s success is immeasurable. Long before Oswald, Disney had stopped drawing to concentrate on running the studio. Iwerks created the images of Oswald and Mickey Mouse and drew most of the first Mickey cartoons. Years later a story circulated that Disney was asked at a party to draw Mickey, and he handed the paper to Iwerks. In the 1930s, Iwerks started his own studio, producing shorts for Columbia Pictures and Warner Bros.’ Looney Tunes series. Iwerks returned to Disney in 1940.

Iwerks later concentrated mostly on visual effects, developing an improved process for combining live action with animation first used in The Three Caballeros (1944) and the xerographic process pioneered in 101 Dalmatians (1961). He won two Academy Awards for his technical work and received a nomination for the bird effects in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). He also helped develop many of Disneyland’s animatronic attractions.

Back in Hollywood, while the rest of the staff finished Oswald shorts for the Universal contract, Disney and Iwerks secretly created the first Mickey Mouse cartoon, Plane Crazy, with the Disney and Iwerks families inking at home after hours. Plane Crazy was drawn entirely by Iwerks at an astonishing rate of approximately 700 drawings per day.

Initially, theater owners resisted running the new cartoons. Mickey Mouse was yet unknown and Disney had no official distributor, but when the third Mickey cartoon came out as an all-talkie, the exhibitors were sold. Adding sound to cartoons wasn’t entirely new, but Disney’s approach was. He realized that sound effects and music should be driven by plot, not added as an afterthought.

If Disney hadn’t lost Oswald to Mintz and Universal, there might not have been a Mickey Mouse. From then on, Disney fiercely protected his copyrights, affecting copyright laws of the U.S. and the world to this day. Mickey and other Disney characters would have long since passed into the public domain if not for the intense lobbying for copyright extensions by the Walt Disney Company.

As for Oswald, he had a life after Disney. Eclipsed by Mickey’s fame, he faded from films in 1938, appearing one last time in 1943. He lasted longer in print, gracing the comic pages through the 1960s in the U.S., and later in Mexico and Italy. In 2004 and 2005, the original Oswald became a pop culture hit in Japan, spawning a craze. Finally, in 2006, the Walt Disney Company reacquired Oswald as part of an assets exchange with Universal. After almost 70 years, Oswald was finally home at Disney, taking his place alongside Mickey and the rest of the iconic Disney characters.

Presented at SFSFF 2009 with live music by Donald Sosin