This feature was published in conjunction with the screening of An Inn in Tokyo at SFSFF 2018

Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo is more than a setting. Like many actors in his films, it appears again and again, adopting different guises, enriching the story on screen. This is evident in his other earliest surviving films, among them An Inn in Tokyo—part of Japan’s enviably long silent period.

TOKYO CHORUS (1931)

“Tokyo … City of the Unemployed” reads an intertitle early in Tokyo Chorus. Ozu’s brilliant Depression-era comedy centers on Shinji (Tokihiko Okada): a salaryman with a wife and three young children, and suddenly, no job. He’s dealing with rising expenses and declining fortunes, just like the city he lives in.

The Tokyo of Tokyo Chorus is moth-eaten and shabby. Its buildings are bleak and its streets are littered with flyers, distributed by men desperate for money; when Shinji visits a restaurant he gets dust on his plate. His office stands in contrast to the crisp, spartan spaces in so many Ozu films: Here the men slouch, eating at their desks; while Shinji sharpens his pencil by poking it through the grill of an oscillating fan. Even the boss’s assistant has a chunk missing from the sole of his shoe. This city’s just one more slapstick clown—full of life, but down on its luck.

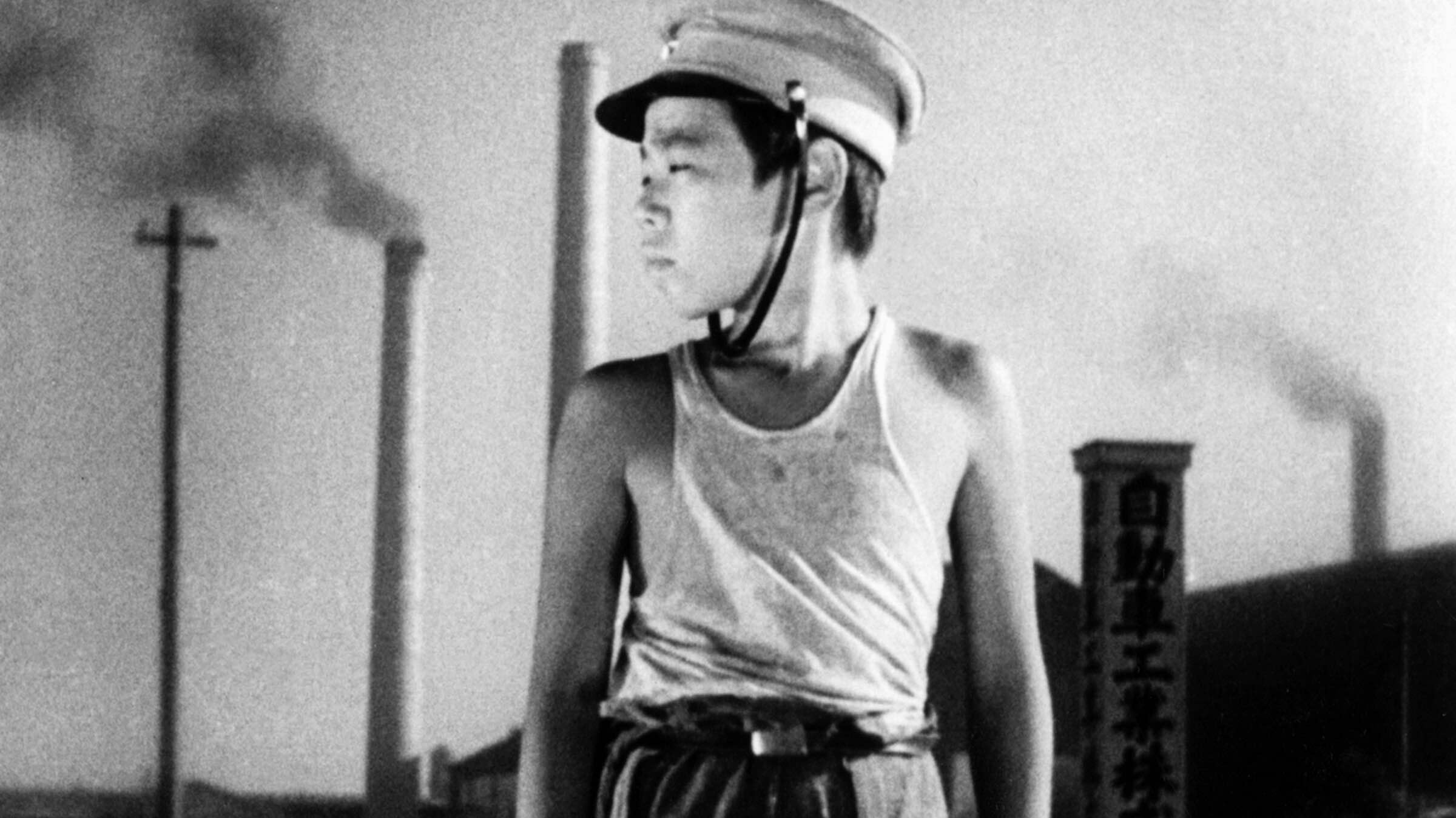

A WOMAN OF TOKYO (1933)

Chikako (Yoshiko Okada) supports her brother Ryoichi (Ureo Egawa), a full-time student. He thinks she works evenings assisting a professor; in fact, she works at a nightclub and may be a prostitute. Woman of Tokyo is about how lives are destroyed by information like this, whispered in private.

The Tokyo of this film is almost entirely enclosed. Action takes place indoors, in living spaces that are claustrophobic, dimly lit. Within these spaces Chikako’s secret is passed from shocked gossip to equally shocked recipient. The night club, on the other hand, is rather well-lit: a space packed with dolled-up women, bottles, and smoke. When we see the outside at all, it is usually dark. Among the few daylight shots is one of a skeletal tree and a pair of thin chimneys—parsimonious, joyless; though Chikako still looks at them with a smile. Only in the closing scene does the film open up, showing us the street where she lives. It is unremarkable. Despite the scandal, this bit of Tokyo could be anywhere.

DRAGNET GIRL (1933)

The Tokyo of Dragnet Girl—to Western eyes, anyway—seems familiar. The characters’ trench coats and hats and gats, the dark alleys and cramped hideaways they inhabit, the brawls they get into at parties and pool halls, all recall classic crime films. We see a Western-style boxing club with a poster advertising a Dempsey title fight and another one for The Champ (1931).

The couple at the center of the film (played by Kinuyo Tanaka and Joji Oka) dream of getting away. “This will be our last job,” they assure one another. “Then we’ll go somewhere where nobody knows us.” It’s the classic dream of the weary crook, but it’s also a desire to leave the City—something that isn’t so easy to do.

EARLY SPRING (1956)

Ozu’s transition to sound brought new depths to his work, but the City remained prominent. The Tokyo of Early Spring (1956) is the clean, bustling center of everything. An early scene shows crowds of young men and women leaving their homes for the commuter trains that will bring them to work. Few of them, we learn, are happy or well-off. Yet to leave Tokyo and its white-collar life is risky. When we meet characters who have done that, they seem uncertain of their choice, even pathetic.

It is telling, then, that Early Spring is about infidelity and the toll it takes on a marriage. To pull away from a marriage is perilous, both emotionally and financially—even if one is unhappy. This Tokyo, too, is hard to escape.

AN AUTUMN AFTERNOON (1962)

Ozu’s final film opens with a beautiful shot: a row of white smokestacks, striped with orange, like candy canes. Urban industry, which bore a distant, ominous quality in An Inn in Tokyo, seems almost exalted here.

Though the plot of An Autumn Afternoon is conservative—concerning a widower, Shuhei (Chishu Ryu), trying to marry off his twenty-something daughter—its Tokyo is bold and bright, transitioning to a new generation. The homes of older people look much as they did in Ozu films from decades before, but the apartment belonging to a younger couple pops with gaudy-colored plastic, like something from a Western magazine ad. Several of the film’s most important scenes take place in “Torys Bar”—advertised with a square sign that Ozu places, red and loud, in the foreground.

The citizens of this Tokyo are nearly twenty years removed from the war. But those who fought in it cannot forget, and the City, now garbed in the language and emblems of the West, will not let them. “If we’d won, we’d both be in New York now. And not just a pachinko parlor called New York. The real thing!” moans a younger veteran to Shuhei’s older one. “Because we lost, our kids dance around and shake their rumps to American records.”

But the City is also wise, and the papering-over of its streetscape with foreign imagery conceals deeper truths. Maybe it’s better that Japan lost the war, Shuhei offers. And his friend, suddenly deflated, agrees. At least, he says, “the dumb militarists can’t bully us anymore.”