Norwegian feature film production in the 1920s was infrequent. It could hardly be considered a major industry at the time; there were very few full-length movies being made annually and very few trained and experienced filmmakers working in Norway. It was quite a sensation when someone suddenly had the nerve to go ahead with a film adaptation of Knut Hamsun’s famous 1894 novel Pan, already a national classic and widely appreciated abroad. The film was well-timed, as Hamsun had received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1920 and was considered one of the country’s biggest heroes.

A talented young actor from the National Theatre in Oslo, Harald Schwenzen, wrote the script and directed the film about the brooding, carnal, back-to-nature Lieutenant Thomas Glahn who takes refuge in Norway’s remote northern territories. The project apparently was a labor of love for Schwenzen—it was his first film as a director and he never made another. For the rest of his career, he concentrated on acting, both for the stage and screen. In Pan, Schwenzen cast his own brother, actor Hjalmar Fries Schwenzen, as the male lead, and Harald himself played Glahn’s hunting companion in the film’s epilogue.

Kommunernes Filmscentral (Norwegian Municipalities’ Film Central), primarily a corporation for the distribution of films, but for some years also credited as a production company, supported the project. Probably the most daring idea for the film was the plan to shoot the epilogue on location in Algeria (the stand-in for the book’s original destination of India). Never before had a Norwegian film crew traveled so far.

In an interview published in the Norwegian newspaper Morgenposten in 1945, Schwenzen talked about the adventure. “We were three of us traveling down to Algeria, my brother Hjalmar, the photographer Tønsberg, and myself, all of us packed for summer holidays, furnished with passports and other suitable things. From Algiers, we traveled farther on the governor’s recommendation, with safe passage by bus or camel, five hundred kilometers down south, through the stone desert and into the sand desert to an oasis, where no Norwegians had ever set foot before; there were only some Arabs and Frenchmen there. And very hot it was—oh my!—forty-five degrees in the shade! And in that heat we were to work from four in the morning until eight in the evening, with a dinner break of two hours. The Frenchmen said we were mad to go on working in this heat, and even the Arabs were skeptical. When we arrived at the oasis we were met with a huge disappointment, and I feared that the whole journey had been in vain: they told us that Arab women were never allowed to leave their houses. And we needed an Arab girl for one of the leading roles, of the Arab girl Maggie, Lieutenant Glahn’s sweetheart. But helped by the powerful French prefect we made contact with a young Arab girl, who was absolutely thrilled to get out of her imprisonment, when she learned that it was properly allowed. And she was a real find! Yes, Falhi, a slim and charming creature, an eighteen-year-old Nature Girl. She appeared to have a natural talent, gracious like a gazelle and extraordinarily flexible. We stayed on there the whole summer, and it was a wonderful time. We were shooting the epilogue of Pan, and it was really great fun to make a Norwegian film in Africa for the very first time.”

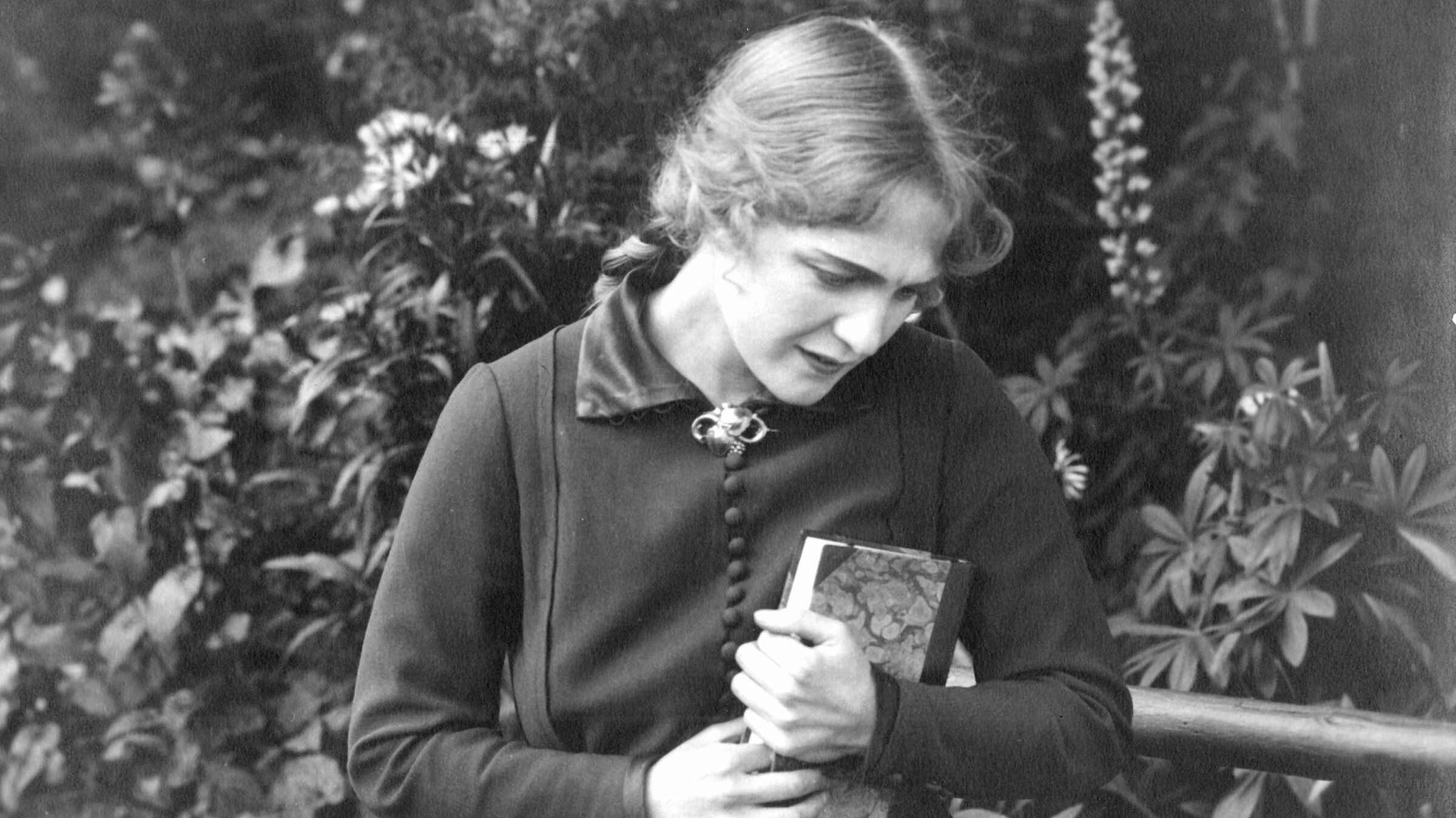

The filming in Algeria was done during the summer of 1921. The main portion of the film was not shot until the following year, in Melbu, in the Vesteraalen archipelago in northern Norway. Two young actresses were hired for the main female leads, Gerd Egede-Nissen as Edvarda and Lillebil Ibsen as Eva. They both had already played film roles abroad, but had never appeared in a Norwegian film before. When the film premiered in the autumn of 1922, it was anticipated with both excitement and skepticism, but the critics were mostly enthusiastic, in some cases amazed. The newspapers generally lavished praise on the film: “The images of Nordland in this film are probably the most beautiful ever seen in a movie,” wrote one. “And what is more, in an excellent way one has succeeded in placing the characters effectively against the surroundings. The strange sentiments of the characters in Pan, which can only be understood with Nature as a background, never seemed unnatural on the screen. This is probably the film’s greatest triumph.”

Another reviewer observed: “The daring step to put the novel Pan on film has succeeded beyond all expectations, due to the film company’s wisdom of casting first-class actors in the leads, and first-class photography. Edvarda is played by Gerd Egede-Nissen. An achievement like this is rarely seen on the screen. Here comes Hamsun’s Edvarda, walking right out of the book, messy and erratic, but intense, lively, and lovely.”

Though warmly received upon its release, it gathered dust in the film archives for decades afterward. Whenever it had been shown in recent years, it was a reprint of an old nitrate print, which was unable to recapture the film’s original picture quality, and in which, sadly, half the film’s epilogue was missing. Happily, the epilogue was reconstituted in the 2012 restoration, using the film’s camera negative (great portions of which were intact) and a safety dupe print made in the early 1960s. The original intertitles did not survive but were reconstructed from the Swedish censorship report and modeled after the style of type in the old print. All earlier safety prints had been produced in black and white, so using the indications in the original material, the tinting was also reconstructed.

Let Harald Schwenzen have the last word, taken from the film’s original program brochure: “The task we have given ourselves is to make a beautiful and artistic pictorialization of this, perhaps Knut Hamsun’s strangest story. Outwardly, there is no strong plot in Pan which could possibly tempt us, but the book is, with its powerful beauty and lyricism, so rich in atmosphere, so characteristic and strong in its human descriptions, that it offers both the director and the actors a very special artistic task. If we have succeeded, through our images, together with excerpts of Hamsun’s text, to give life to these people and this atmosphere, as in the book, then we have fulfilled the great task we set for ourselves.”

—Bent Kvalvik

THE AUTHOR AND THE ACTOR

Knut Hamsun once wrote that the purpose of literature was “to pursue thought in its innermost concealed corners, on its darkest and most remote paths, in its most fantastic flights into mystery and madness, even to the distant spheres, to the gates of Heaven and Hell.” Some of literature’s first truly modern works, Hamsun’s early plotless psychological novels, Hunger, Mysteries, and Pan, presented both a great temptation and challenge for moviemakers. That Harald Schwenzen chose to adapt Pan as a first-time director is both surprising and, as an accomplished actor, fitting. Who better to interpret what Hamsun describes as the “secret stirrings that go on unnoticed in the remote parts of the mind, the incalculable chaos of impressions, the delicate life of the imagination seen under the magnifying glass; the random wanderings of those thoughts and feelings; untrodden, trackless journeyings by brain and heart, strange workings of the nerves, the whispers of the blood, the entreaty of the bone, all the unconscious life of the mind” than an actor whose primary purpose is to express a character’s inner motivations?

Schwenzen was one of Norway’s leading stage actors at the National Theater, Oslo, from his debut there in 1918 until his death in 1954. In the early years, he played attractive roles such as Peer Gynt in Ibsen’s play and Don Carlos in Schiller’s, as well as Orsino in Twelfth Night and Sebastian in The Tempest. He also occasionally directed in the theater and moved on to play darker characters in later years. He appeared in his first film in Sweden, in Victor Sjöström’s Masterman (1920). After Pan, his sole outing as director, he returned to Sweden and appeared in Elis Ellis’s Två konungar (1925) and Gustaf Molander’s Till Österland (1926). His last silent film role was back in Norway, in George Schnéevoigt’s Laila (1929). His destiny could not have differed more strikingly from that of Pan author Knut Hamsun, who began to champion Nazism during the 1930s and once had a private meeting with Adolph Hitler. During World War II, Schwenzen worked actively in the resistance against the Occupation, and in 1944 was sent to, and survived, the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

The author Hamsun, whose wife and sons were imprisoned after the war as collaborators, was deemed too “permanently impaired” for prison but was condemned for treason and stripped of all his wealth. He died at age ninety-two in poverty and disgrace. He turned his postwar experiences into his final novel, On Overgrown Paths, published in Norway in 1949 and still considered one of his finest works.

Presented at SFSFF 2015 with live music by Guenter Buchwald