This historical reprint was published in conjunction with the screening of Rapsodia Satanica and L’Inferno at SFSFF 2019

PARLA UNA SPETTATRICE

In which the author addresses Italy’s poets, novelists, and playwrights distressed by the lowbrow fare at the movies.

I don’t deny that the novelist and writer named above—myself—has, with her companions in the very same toil, often vigorously discussed potentially remarkable and beautiful but utterly forgotten stories from the names that live on in literary history; stories which for the most part flash across the reality of the cinema like an immense rocket on a summer night, momentarily lighting the firmament only to leave behind a denser darkness and the stink of burned gun powder …

Then, for months and months, and with a feeling of sincere humility, I did only one thing: I went to the movies to take up my role of spettatrice. With my mortal eyes, I went to see, for a few cents, or even less, whatever might please, amuse, or move me in a film show. I sat in a corner, in the dark, silent and still, like all my neighbors; and my anonymous and unknown persona because like many others, anonymous and unknown, who were sitting in front of, behind, or beside me. I was like them, an ordinary spectator, without preconceptions, without prejudices, without any sort of bond to anything or anybody. I did not have any ideas or opinions, nothing of anything crammed my mind, which because pure and childlike, spending so little money, staying in that darkness, in that silent and stationary anticipation. And do you know what happened? I experienced the very same impressions felt by my neighbor on my right, who was, I suppose, a shop assistant; the same ones felt by my neighbor on my left, who, now urbanized, has formerly been, I think, a little provincial. And when the lady sitting in front of me laughed, I laughed too because in the dark everybody was laughing; and if the lady behind me cried, I started crying like her and like all the others who were doing the same.

And so, I became a perfect spettatrice, by going from show to show, watching all those stories on the white screen, startling at a sudden appearance or threatening danger, a-throb with the anguish for the heroes of an unknown drama, or with the mortal risk run by a sweet character, destined to die. This spettatrice became convinced of a truth—let us say, an eternal truth—that the audience of the cinematography is made of thousands of simple souls, who were either like that in the first place or made simple by the movies themselves. For one of the most bizarre miracles occurring inside a movie theater is that everyone becomes part of one single spirit. This common spirit gets bored with, or angry at the characters’ entanglements, the intricate episodes, the written and often fleeting intertitles, which force it into extremely rapid mental effort. In addition, it is impressionable and tender, sensitive to the real and sincere affections; honorable and right—perversity and meanness astonish, yet outrage it. Attracted, but not deceived by the exterior beauty of actors and actresses, it is disappointed if their acts and faces reveal no interior life. Plain but highly sentimental forces like love and pain can deeply affect such an innocent thing.

Oh, poets, novelists, playwrights, and brothers of mine, we should not strive so anxiously and painfully for rare and precious scenarios for our films! Let’s just go to the truth of things and to people’s naturalness. Let’s just tell plain good stories, enriching our craft from life itself and take on that elusive but passionate aura of poetry, which springs from our overflowing heart. Stories in which every man and woman would be human, in the widest or humblest meaning of the world; stories in which tragic, dramatic, ironic, or grotesque performances would merge in that unlikely harmony of human events. Dearest friends, it is a spettatrice speaking to you, a spettatrice who now asks herself, in retrospect, the reasons for her tears, her smiles, her boredom. This woman who is speaking to you is a creature of the crowd, it is she whom you should move, who you should please …

An excerpt from “Parla una spettatrice,” which first appeared in the June 15, 1916, issue of L’Arte Muta. Translated into English by Giorgio Bertellini and published in Red Velvet Seat: Women’s Writing on the First Fifty Years of Cinema, edited by Antonia Lant and Ingrid Periz.

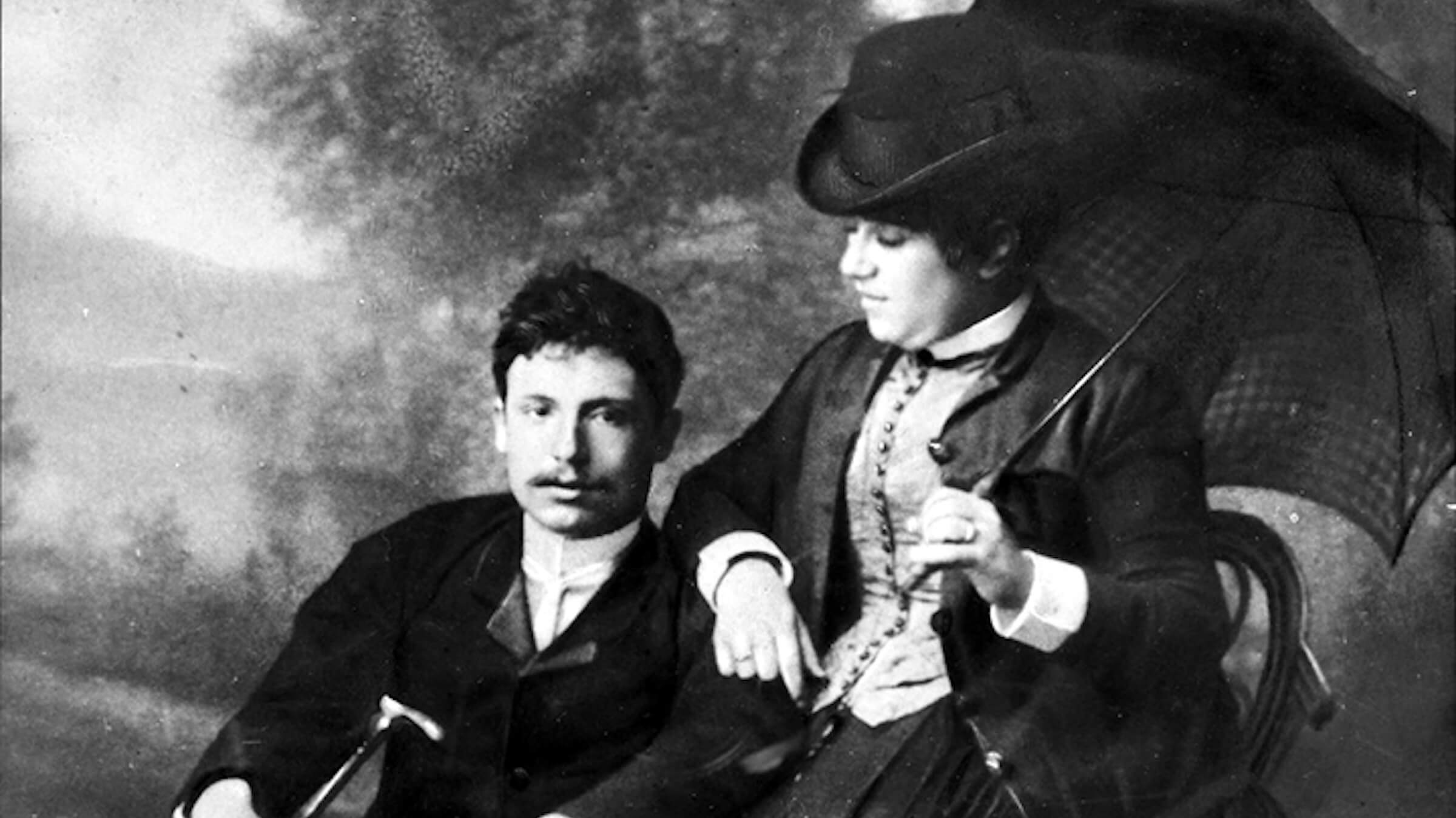

ABOUT MATILDE SERAO

Author of more than forty novels and short stories, Matilde Serao wrote the first critique of the movies by an Italian intellectual, the title of her 1906 article, “Cinematografeide!,” playfully equating the craze for the novelty amusement to a contagious disease. She founded newspapers in both Rome and Naples—two with her husband Edoardo Scarfoglio—and her influence encompassed all of Italy. Serao championed Neapolitan cinema as a popular art, frequently contributing reviews to Gustavo Lombardo’s film publication L’Arte Muta and writing scripts of her own. Her first scenario was realized by “Za La Mort” creator Emilio Ghione, but, as Anita Trivelli writes in her profile of Serao for the Women Film Pioneers Project, no trace of this or her other scripts is known to survive. Influential, prolific, principled, and beloved, Serao was vocally anti-Fascist and her nomination for the Nobel Prize in Literature, supported by her colleagues, was passed over four times by the time she died in 1927. To this day, Naples’s legendary gathering spot Caffè Gambrinus serves a cone-shaped pastry filled with cream and wild strawberries created in her honor, called La Matilda.