Lev Vladimirovich Kuleshov was born in Tambov, Russia, in 1899 and came of age in a turbulent world. Civil war gripped the country. Cinema, like the dream of socialism, was in its infancy. As a set designer under the Tsarist filmmaker Yevgeni Bauer, the young Kuleshov was already writing about the role of the artist in the filmmaking process. In 1917, when Bauer died while building a studio in the Crimea, Kuleshov got his big break in finishing The King of Paris. The following year at the tender age of 18, Kuleshov directed his first film, Project of Engineer Prite, a detective story that was the first Russian production to use American-style montage. Under the Bolsheviks, Kuleshov was put in charge of re-editing newsreel footage and imported features. He was also sent to the frontlines during the Russo-Polish War, where he shot On the Red Front (1920), which combined documentary footage and dramatized action.

Despite his achievements, Kuleshov was considered too young and inexperienced for a position at the newly opened Moscow Film School. However he and several colleagues, among them Vsevolod Pudovkin, Sergei Kamarov, and Alexandra Khokhlova (Kuleshov’s future wife and lifetime collaborator), were allowed to start an experimental group of actors and directors known as the Kuleshov Workshop. It was here that Kuleshov put his radical theories into practice. In the most famous of his experiments, Kuleshov placed a shot of well-known actor Ivan Mozhukhin, a neutral expression on his face, in juxtaposition with a bowl of soup, a young girl holding a toy bear, and a woman in a coffin.

Viewers of the footage assigned different emotions to the actor depending on which shot had appeared before, demonstrating that it was not the photographed reality that was of primary importance in giving meaning to films, but the sequence of shots and the audience reaction to that sequencing. This became known as the Kuleshov Effect. He also studied Chaplin’s use of close-ups and developed the actor-mannequin theories of film acting, which were in direct opposition to the popular Stanislavsky method of the time. He believed that actors should use a minimum amount of gesture and movement, and he recognized that close-ups were powerful in expressing emotion.

Kuleshov directed the 1924 comedy The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks and The Death Ray, a science-fiction film released in 1925. Both were a departure for Soviet cinema and were roundly criticized for their experimental nature and lack of appropriate ideological content. Kuleshov was marked as a formalist and had trouble receiving funds for further projects. Working with scriptwriter Viktor Shklovsky, he decided to film Jack London’s short story “The Unexpected.” London was a well-known socialist sympathizer and his stories were familiar to Russian filmmakers. His novels Martin Eden and The Iron Heel and his short story “A Piece of Meat” (produced as Gold by the Kuleshov Workshop) had all been adapted for the silent screen. “The Unexpected,” with its small number of characters and few locations, lent itself to the C-class budget of 15,000–18,000 rubles.

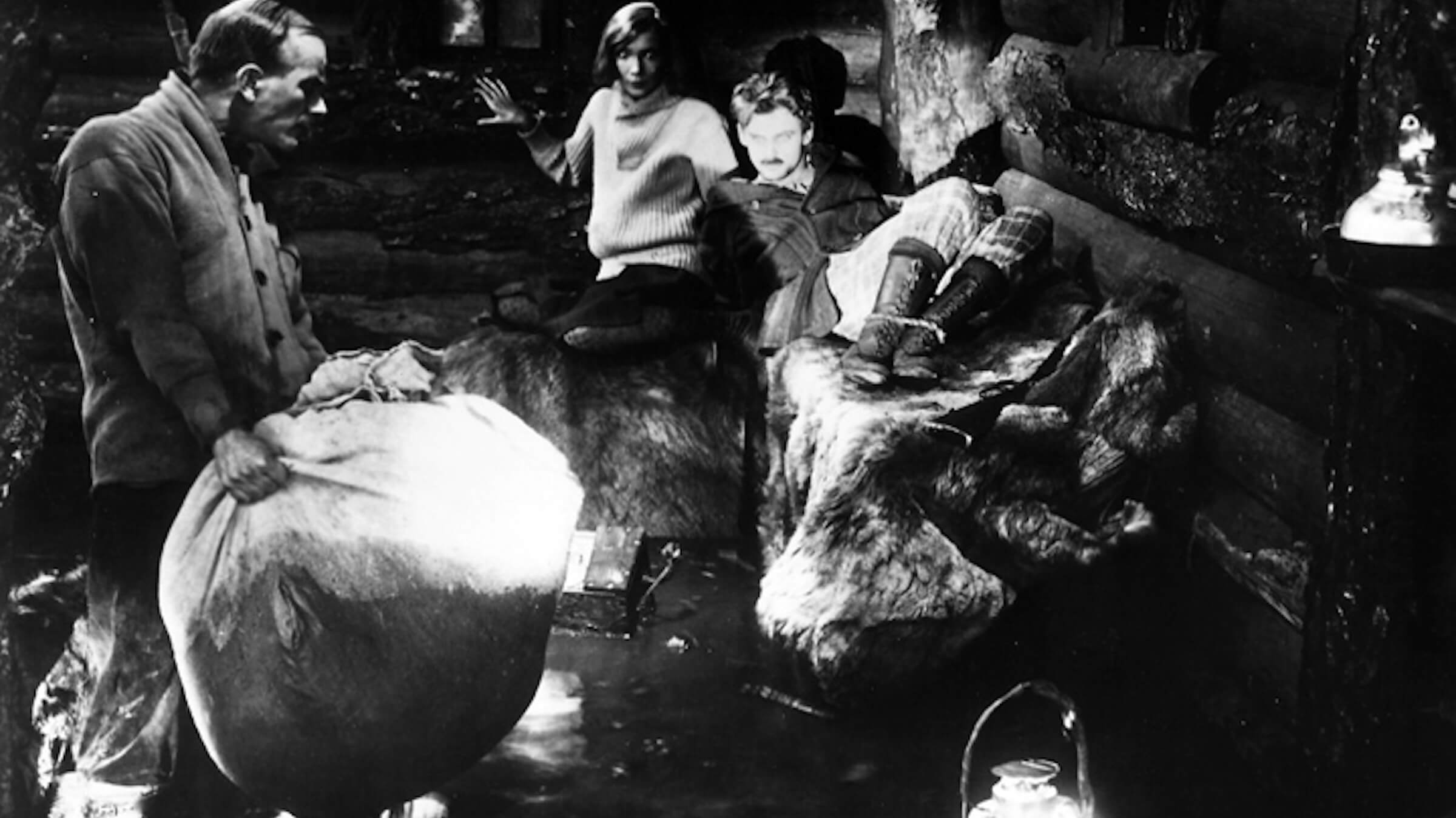

Po Zakonu (By the Law) became a model of economic filmmaking. The cast and crew rehearsed action and camera setups in the evenings for the next day’s shooting. Two small sets were built in the courtyard of First Studio near what is now Kiev Station. Three actors were paid salaries while the other two, former Workshop members Podobed and Galadzhev (Harkey and Dutchy respectively), volunteered their time. It is still considered the lowest-budget Russian feature ever made.

The film was well received by the European avant-garde for its ability to sustain psychological tension without the use of orthodox film techniques. Joseph Freeman described the film’s strength as the result of being “worked out in the spirit of an algebraic formula, seeking to obtain the maximum of effect with the minimum of effort.”

Despite critical acclaim, Po Zakonu further isolated Kuleshov from the Bolsheviks, who were primarily interested in promoting revolutionary goals. His reputation as an artist interested in form not content persisted and, with the implementation of the first Five Year Plan in 1927, Kuleshov was forced to recant many of his theories. He was permitted to make only a few more films and turned his attention to writing instructive texts and teaching. In 1944 on the recommendation of Eisenstein, Kuleshov was appointed head of the State Institute of Cinematography, where he remained until his death in 1970. He received recognition from Soviet officials in 1967 when he was awarded the Order of Lenin.

Presented at SFSFF 1999 with live music by Michael Mortilla

Intertitle translation read by Dmitri Poletaev