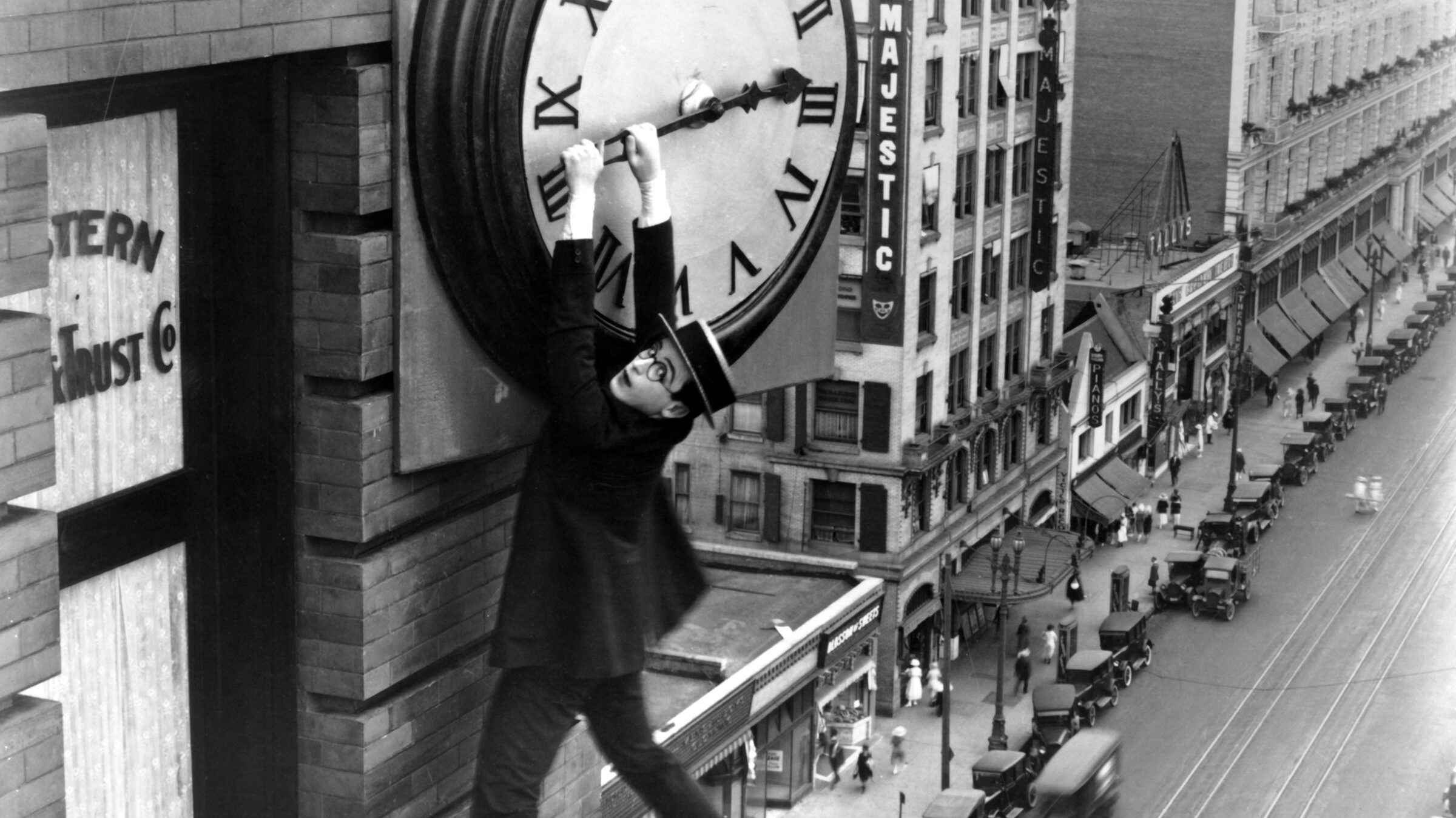

Harold Lloyd will forever be associated with Safety Last! because of a single image. Even people who have never seen a Lloyd film are familiar with the iconography of a bespectacled man hanging off the hands of a collapsing clock on the side of a skyscraper high above teeming city streets. It is one of the most celebrated images in cinema.

Safety Last! was Harold Lloyd’s fourth and most complex “thrill” comedy. He came upon the idea for the film after witnessing a so-called “human fly” climb up the side of a tall building—a typical spectacle in the stunt-crazed America ofthe 1920s. Nearly forty years later Lloyd recalled the genesis of the film: “Without too much ado he started at the bottom of the building and started to climb up the side of this building. Well, it had such a terrific impact on me that when he got to about the third floor or fourth floor I couldn’t watch him anymore. My heart was in my throat and so I started walking up the street … but, of course, I kept looking back all the time to see if he was still there. Finally, I went around the corner. Silly as it is, I stood around the corner so Iwouldn’t watch him all the time, but every once in a while I’d stick my head around the corner and see how he was progressing. I just couldn’t believe he could make that whole climb, but he did … So I went back, went into the building, got up on the roof and met the young man, gave him my address, and told him to come out and visit Hal Roach and myself. His name was Bill Strother.”

Hal Roach (Harold Lloyd’s producer) placed Bill Strother under contract and devised a rough idea of a story involving a daredevil climb. The film was constructed around this comedy sequence and introductory material was later built around it.

The plot of the film has Lloyd as a country boy who sets out from his hometown of Great Bend to make good in the big city. His sweetheart (Mildred Davis, Lloyd’s real-life wife) promises to marry him once he is a success. Lloyd is only able to get a position as a lowly dry goods clerk is a department store, although he writes his girl at home telling her he is one of the store executives and that it will only be a matter of time before he will send for her. His chance to succeed arrives when he overhears the general manager pledge to pay $1,000 to anyone who can draw a large crowd to the store. Lloyd successfully proposes that the general manager hire his roommate (Bill Strother), who works as a steeplejack, to be a human fly and climb the side of the department store building. On the day of the publicity stunt, Strother is forced to dodge a disgruntled police officer (Noah Young) who has been after him, and Lloyd has to make the climb himself.

The excellence of Safety Last! is not confined to Lloyd scaling the skyscraper; the five reels that lead up to the climb provide the necessary context for it. Lloyd’s impersonation of the store manager sets up one of the film’s dominant themes, illusion, which is conveyed not only through Lloyd’s role, but also through the camera’s role in making the audience believe the impossible. The idea is set up in the film’s first shot: Lloyd depicted behind bars, until the camera backs up to reveal the truth.

Lloyd’s scaling of the building is a classic sequence in which comedy at its most inspired and suspense at its most excruciating are ingeniously interwoven— the climb is the grand finale to the superb gags that precede it. As he climbs higher and higher, more complex obstacles confront him, from a flock of pigeons to entanglement in a net, to a painter’s trestle, to a swinging window, to the clock itself. “Each new floor is like a stanza in a poem,” wrote Pulitzer Prize-winning author,poet, and critic James Agee. While Lloyd navigates these travails, the audience’s hysteria escalates. It was not uncommon for 1920s spectators to hide their eyes or even faint when watching these portions of the film. Many cinemas reportedly hired a nurse or kept ambulances on call outside the theater.

Lloyd never revealed exactly how his most famous sequence was achieved, but a report by journalist and writer Adela Rogers St. John, Lloyd’s autobiography, later interviews with Lloyd, still photo- graphs, and Los Angeles topography reveal how the climb was accomplished. Few special effects were available at the time, and the techniques that could be employed—such as mirrors, double exposure, glass shots, or hanging miniatures— were not used. The production worked from three different buildings at various stages of the climb (Broadway and Spring Street, Broadway and Ninth, and Broadway and Sixth) and shot from angles that could accomplish an overemphasis of perspective and distance.

Lloyd was a good athlete and did many of the climb shots himself, but there were limits. His insurance company did not allow him to do the entire sequence; an injury to the star could shut down the entire production and jeopardize the studio. Also, Lloyd had only one complete hand—the result of an accident in 1919 in which he lost his right thumb and forefinger. (The disfigurement was concealed in films with a specially made flesh-colored glove).

The long shots of Lloyd climbing the building were not Lloyd but Bill Strother (who climbed the International Bank Building in Los Angeles on September 17, 1922, with four cameras covering the action, under the supervision of Roach). For a few additional moments (such as the two shots in which Lloyd swings the length of the building by a rope), a circus acrobat was used. For one shot—in which Lloyd hangs from the building edge as a result of a mouse crawling up the leg of his trousers—assistant director Robert A. Golden (who routinely doubled for Lloyd from 1921 to 1927) “hung in.”

Audiences naturally assume that Harold Lloyd was actually hanging off the clock hands many stories above the street, and they are correct. However, Lloyd was hanging on a clock built on a platform near the edge of the top of a building at 908 South Broadway. Again, the crew used in-camera tricks designed to conceal the platform—which was approximately fifteen feet below, out of frame—and perspective shots to make the clock appear on the side, not on top, of the building.

High angle shots of the busy streets below contributed to the illusion of height. To this day, the effect is remarkable. Although many techniques of silent cinema appear dated, the climb is still completely convincing. The clock sequence remains one of the most effective and thrilling moments in film comedy—a visual metaphor for the upwardly mobile everyman of the 1920s and the extent to which he climbs to achieve the American Dream.

Safety Last!—and the genius of Harold Lloyd—continues to dangle over all who attempt to fuse comedy and thrills in the movies.

Presented at A Day of Silents 2023 with live musical accompaniment by Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra and Nicholas White