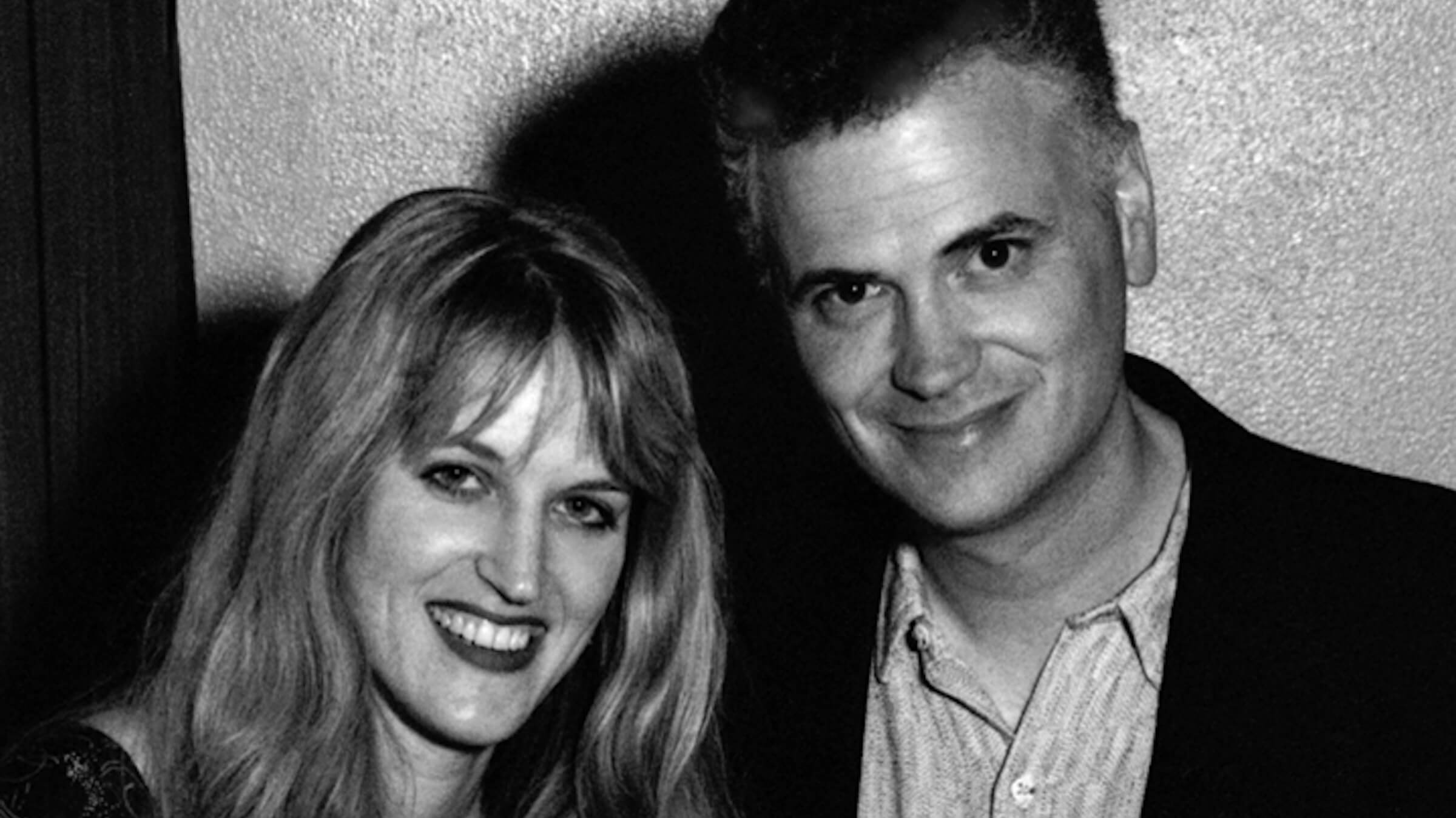

At the end of the 20th century, Melissa Chittick and Stephen Salmons had a dream to share their love of silent cinema with fellow San Franciscans and they founded the Silent Film Festival. Fifteen years later, the reality of their amazing creation has outstripped their wildest dreams. Today, the Silent Film Festival is the most important festival of its kind in the Americas, and a treasure for the world-wide community of film lovers.

We congratulate Melissa and Steve on their brilliant vision, and extend our hearty thanks. Since 1994, the Silent Film Festival has been presenting silent films at the Castro Theatre, San Francisco’s ornate, gilded wonderland of wildly different architectural styles, designed to make any first-time moviegoer drop their jaw and say, “Wow,” in dumbstruck appreciation. Built in the silent era, it is a palace well suited to an experience increasingly difficult to encounter: the live performance of a musical score to a silent film or, as it has been characterized by the great film historian Kevin Brownlow, Live Cinema.

Audiences at the Silent Film Festival are able to experience the nearly-but-not-quite-lost art form of Live Cinema. It’s how the first filmmakers, who discovered how to tell stories in moving pictures, meant for you to see—and hear—their films. It’s how people saw films in the silent era, in every movie theater, in every city, every night of the week. To refer to a film made between 1895 and approximately 1929 as a silent film is to ignore what accounts for, at the very least, half the experience of watching a silent film: the musical accompaniment that exponentially increases the joy of the experience.

The marriage of filmed images to live music can produce an experience so emotionally direct, it can make you feel like you’ve been hit by lightning. Withhold the down-to-earth, humdrum reality of talk and put in its place the vibrant, head-in-the-clouds beauty of music, and you find yourself responding to the film’s narrative with complete empathy.

Silent films aren’t dialogue-free; characters do talk to each other. We don’t hear what they say. Instead, we read it, on title cards. We read it to ourselves, in our own heads, in our own voices, and this makes the experience even more direct, more personal. Douglas Fairbanks, Louise Brooks, Charlie Chaplin, Clara Bow—these stars sound like every single one of us. Silent films were quickly recognized as a powerful art form not only for their dynamic visual appeal, but for the way they engage our imaginations, requiring us to play a role by contributing our own inner voices. We’re in the film, we’re part of the story, it’s happening to us just as much as it’s happening to Rudolph Valentino.

I hope you’ll forgive me if I go out on a limb here, but I’m fairly convinced that movies were the greatest invention of the previous century. Others might name penicillin, the gas-piston engine, or even the Swanson TV Dinner, but me, I’ll take movies. They opened up the world, brought it to our neighborhoods, entertaining and educating us on a scale never before thought possible. We were taken to the farthest corners of the earth, where we saw people like us, looking back. Movies gave us our first real opportunity to experience our common humanity. And within just a few short years of their invention, they matured into a completely original, indelible art form, unlike anything seen before.

At first, filmmakers photographed their stories from a single camera angle, which showed the action from a remove, in imitation of the experience of watching a play in a theater. Soon enough, filmmakers tried new things: cutting one scene together with another scene to suggest that the two scenes were occurring simultaneously in different places; changing camera angles during a scene, controlling what the viewer was able to see, unlike in the theater; and, perhaps the greatest discovery of all, putting the camera exclusively on a character’s face. Today it’s commonly known as the close-up, and we’re used to it; we expect to see a character up close. But it was an absolute revelation to filmmakers of the silent era. They could put you just inches away from the face of a person and let you stare at it, let you invade their personal space, as we say today.. Add music to that, and you became positively telepathic. If the musician played a sentimental ballad, you’d know that person must be sad; if a foxtrot, you’d know they were happy—and the actor playing that person wouldn’t have to do anything more than widen their eyes or lower them.

There’s a common misconception that the acting in silent films is broad and unsophisticated— lots of arm waving and chest thumping, playing to the last seat in the house. Not so. For those of you who are experiencing a silent film for the first time as it’s meant to be seen and as it’s meant to be heard, you’re in for a real treat, perhaps even a revelation.