The author of Eros im Zuchthaus, the basis for Sex in Chains, wasn’t going to wait around for the world to change. Karl Plättner was well known to authorities as a troublemaker from his rebellious adolescence through his years as an ironworker and political organizer. Drafted at the start of World War I, he was discharged a year later with three permanently crippled fingers and joined the antiwar effort, getting repeatedly detained for distributing leaflets. While the old order crumbled—the Ottoman, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires fell almost simultaneously—he simmered in prison for a year and a half awaiting trial. When Germany began to roil with revolution in 1917, he was freed in a general amnesty. Fired up by what must have seemed like a red wave of worker uprisings about to sweep Europe, Plättner cofounded a branch of the International Communist Party and did battle in the streets against proto-fascist militia called Freikorps. When the November Revolution failed, Plättner became a man on the run, leading a Robin Hood-style gang that redistributed funds from banks, post offices, and company coffers. Caught in 1922, he was sentenced to a ten-year stretch and shuffled from institution to institution for bedeviling officials with demands to improve prison conditions. He also began gathering the research on the sexual life of inmates that resulted in his book describing the distress caused by prolonged denial of a basic human need, sex. Released in 1928 as the result of another amnesty, Plättner finished Eros im Zuchthaus with the help of Magnus Hirschfeld’s Sex Institute, known for its advocacy of homosexual rights but which also provided health services like birth control advice in poor communities. Hirschfeld himself wrote the preface for the book when the institute published it in 1929, complete with a set of form letters for taking action.

Scholar Christian Rogowski surmises that director Wilhelm Dieterle obtained a pre-publication copy of Plättner’s book (through Austrian writer Franz Höllering) to make Geschlecht in Fesseln, or Sex in Chains. Already an accomplished actor and director by this time, Dieterle caught the acting bug at sixteen while apprenticing as a carpenter. Supporting himself working as a stagehand, he eventually excelled enough as an actor to join Max Reinhardt’s famous Deutsche Theatre where intimate kammerspiel productions were revolutionizing theater. He earned praise for his expressive and commanding performances in films by some of the most innovative directors working in Germany, Richard Oswald, Paul Leni, and E.A. Dupont among them. Of his role as Valentin in F.W. Murnau’s Faust, set designer Robert Herlth later said, “[the] mother’s room became merely a frame for the robust present of Dieterle.” In 1923, he self-financed his directing debut, Der Mensch am Wege, which he also wrote and starred in, a trend he maintained throughout his German career. By 1928, Dieterle had set up an independent production company with actress and writer Charlotte Hagenbruch, to whom he had been married since 1921.

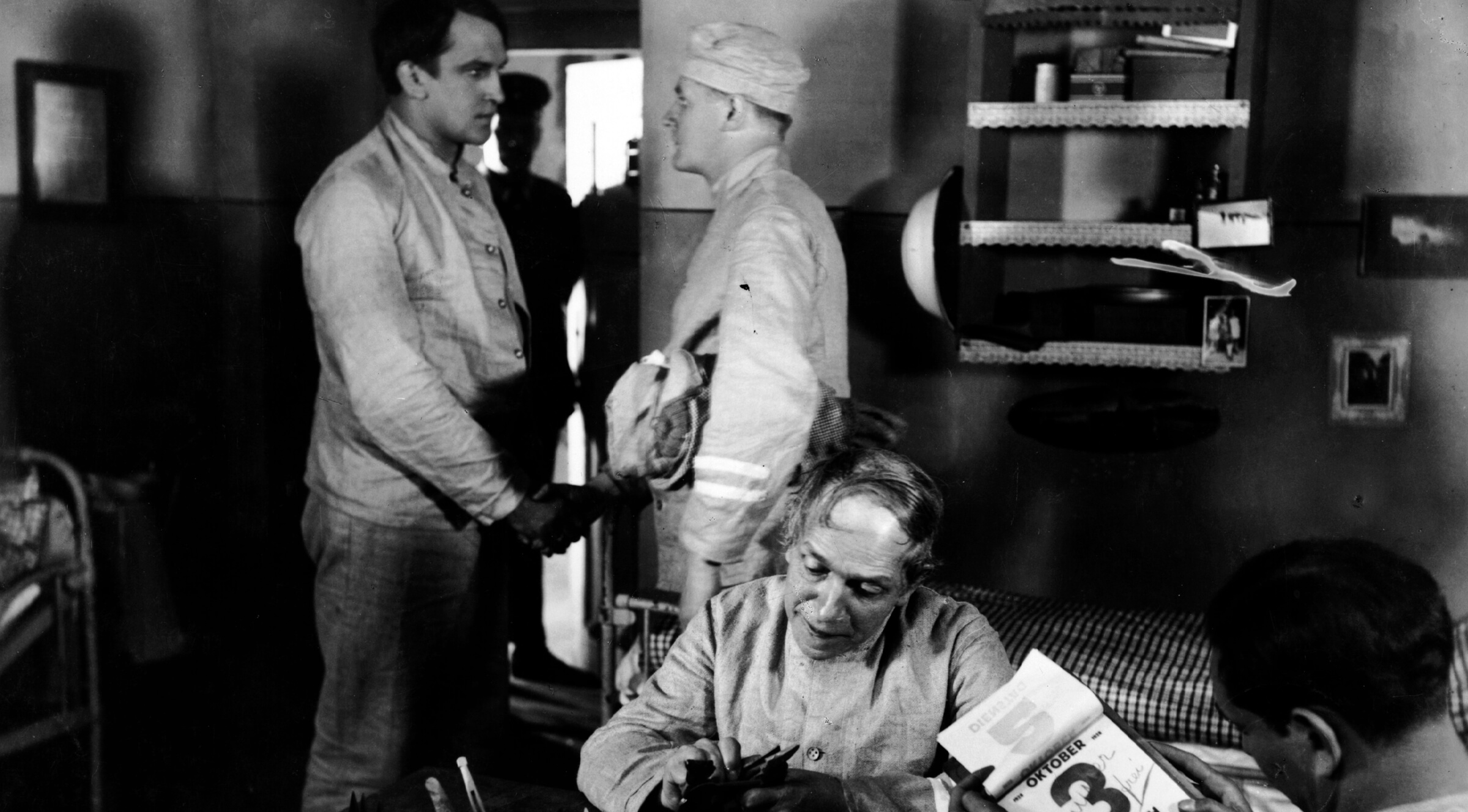

For Sex in Chains, Plättner’s research was streamlined into a single story of a man and a woman forced to endure a long separation. Dieterle had learned well how to transfer the intimacy of kammerspiel to the screen, creating a tender portrayal of the young married couple struggling in the Weimar-era economy. The husband (played by Dieterle) suffers the subtle indignities of someone no longer able to provide and the wife (halo-haired Swedish actress Mary Johnson) tries to maintain appearances with neighbors and disapproving family. Moviegoers in postwar Germany would have been able to relate to the couple’s fall from middle-class grace and Dieterle makes it easy for audiences to care.

Suddenly, their story takes a much darker turn. A cigarette girl at a nighttime beer garden to help make ends meet, the wife is sexually harassed by a violent customer, and her husband, waiting to escort her home, defends her in an escalating confrontation. From the coziness of home to a cramped cell of prison, the husband now faces the deprivations of incarceration, and his wife the absence of a breadwinner and lover. Prisoners are depicted as repressing sexual desire in increasingly destructive ways, going mad doing so, or resigning themselves to homosexuality for the duration. As with the couple, Dieterle wants us to regard these men with compassion, showing one frustrated inmate sculpting a female figure from his bread ration, an incident preserved from Plättner’s book. Dieterle’s young lover, the fresh-faced Hans Heinrich von Twardowski, is portrayed with almost as much tenderness as the wife, the men’s first assignation represented by a lingering shot of their fingers beginning to intertwine across bedposts. Even as the film is billed as gay-themed today, it falls far short of endorsing homosexuality especially as Twardowski’s character reappears as a threat in the latter part of the film.

Dieterle’s goal was to advocate for prison reform, specifically conjugal visits for inmates, so he tried hard to avoid arousing the outrage of moralists. He left out the more graphic elements in Plättner’s book and fleshed out the wife’s storyline, giving her situation equal time on-screen. Critics deemed the effort a success. Film-Kurier’s reviewer noted that the audience met it with “strong applause” and praised it as both entertaining and persuasive. Reichsfilmblatt reported that Dieterle “raises a delicate subject with seriousness.” Still, many cuts were made by censors, in particular to the scene of the wife as she pounds on the prison door desperate to be reunited with her husband (Germany’s “new woman” could not be so liberated that she actually wanted sex). There was no pleasing rightwing quarters, however, and Dieterle wrote a passionate article defending Sex in Chains against accusations as Tendenzfilm, or propaganda, a charge that threatened the film’s tax status: “Tendentiousness as art! Tendentiousness toward making the subject matter come alive, not to bore, but to go ahead and entertain, to stimulate thinking.” When a dry bureaucratic letter dismissed a last-ditch effort to ban the film—because it used government facilities in the production—it must have felt like vindication.

A Weimar citizen could have easily presumed that individual civil liberties would simply continue to advance. The interwar era saw plenty of volatility and despair but also openness to improving the lives and conditions of working people, increased independence of and respect for women (the Weimar constitution outlawed discrimination against women in the civil service), tolerance (in the big cities at least) toward new gender identities and the thriving Jewish population then stamping its enormous mark on the country’s cultural life. But it took only ten years—from the beer-hall putsch in 1923 to the National Socialists victory in 1933—for Hitler to go from a fringe figure of ridicule to absolute dictator. The very year the Nazis seized power, Sex in Chains was permanently banned. That life could turn ugly all of a sudden was not merely a melodramatic device for movies.

Dieterle had already left for the U.S., accepting a studio offer to direct German-language versions of talkies in 1930. He went on to become an A-list director in Hollywood, compiling a sizable and eclectic body of work, including a series of acclaimed biopics, one of which, 1937’s The Life of Emile Zola, garnered him an Oscar nomination. He hadn’t left his politics behind and directed the early antifascist film Blockade in 1938 and, in 1939, cofounded the antifascist publication The Hollywood Tribune with Hagenbruch and another German émigré director E.A. Dupont. His efforts got him “graylisted” during Hollywood’s Red Scare and he eventually returned to Germany.

Karl Plättner had stayed. He came to prefer writing to street-fighting and distanced himself from International Communism with the rise of Stalin, but the Nazis already had him on their lists. He was sent to concentration camps in 1933, 1937, and, in 1939, was condemned to a long tortuous shuffle among the deadliest, Buchenwald included. He was miraculously alive when American troops arrived in 1945, and he and another prisoner cut through the fence to free themselves. Trying to make his way home, the fifty-two-year-old succumbed at a hospital in Freising a month after Victory in Europe was declared. We don’t know what hopes, if any, Plättner still harbored for changing the world when he died.

Presented at A Day of Silents 2017 with live music by Philip Carli