Stefan Drössler received the 2023 SFSFF Award for commitment to the preservation and presentation of silent cinema at the screening of A Daughter of Destiny at SFSFF 2023

World cinema owes an incalculable debt to Germany. Some of the greatest and most iconic treasures ever committed to film come from the fertile imaginations and technical ingenuity of German filmmakers, from the big-budget Ufa spectaculars to the many independent productions that made their way to screens around the world, not to mention the German actors and directors who brought their expertise to the nascent Hollywood film industry. One iconic film, F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), sparked a passion for film in Stefan Drössler, this year’s recipient of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival Award for his contributions to silent film preservation, restoration, and exhibition.

A lifelong film enthusiast, Drössler established in 1985 what is now the Bonn Summer Cinema – International Silent Film Festival. He was director of the Bonn Kinemathek from 1986 to 1998 and has been director of Filmmuseum München (Munich Film Archive) for the past twenty-four years. Drössler was a longtime member of the Film Advisory Board of the Goethe-Institut and is one of the founders of the DVD label Edition Filmmuseum, which publishes archive treasures and film restorations. He spoke with me about his early film experiences and the work that went into A Daughter of Destiny, or Alraune as it is known in German, written and directed by Nosferatu scriptwriter Henrik Galeen.

How did your cinephilia begin?

My mother thought that all these moving images are a bad influence. This initiated my interest in this forbidden fruit and I tried to see as many films as I could. When I saw an interesting one, I wanted to share it, so I founded my school film club. When I got some films in bad condition or as incomplete prints, I tried to combine two prints to get the full film. This was my very first step in so-called film reconstruction, and I found it thrilling.

The first silent film I saw as a child was on television. It was Nosferatu and it impressed me a lot. Then, much later, in the late ’70s, I attended a lecture by the film historian Enno Patalas from the Munich Filmmuseum who had started to reconstruct the movie. He presented the first reel of his workprint. I was very impressed how much longer it was than what I had seen! I told myself, “One day, when this restoration is finished, I will present it in my film club.” It needed some years, but at last, in 1987, I was able to present the restored Nosferatu. Enno personally came because he just had inserted the pink tints in the dawn scenes and wanted to view them on the big screen.

Tell me about your work on A Daughter of Destiny?

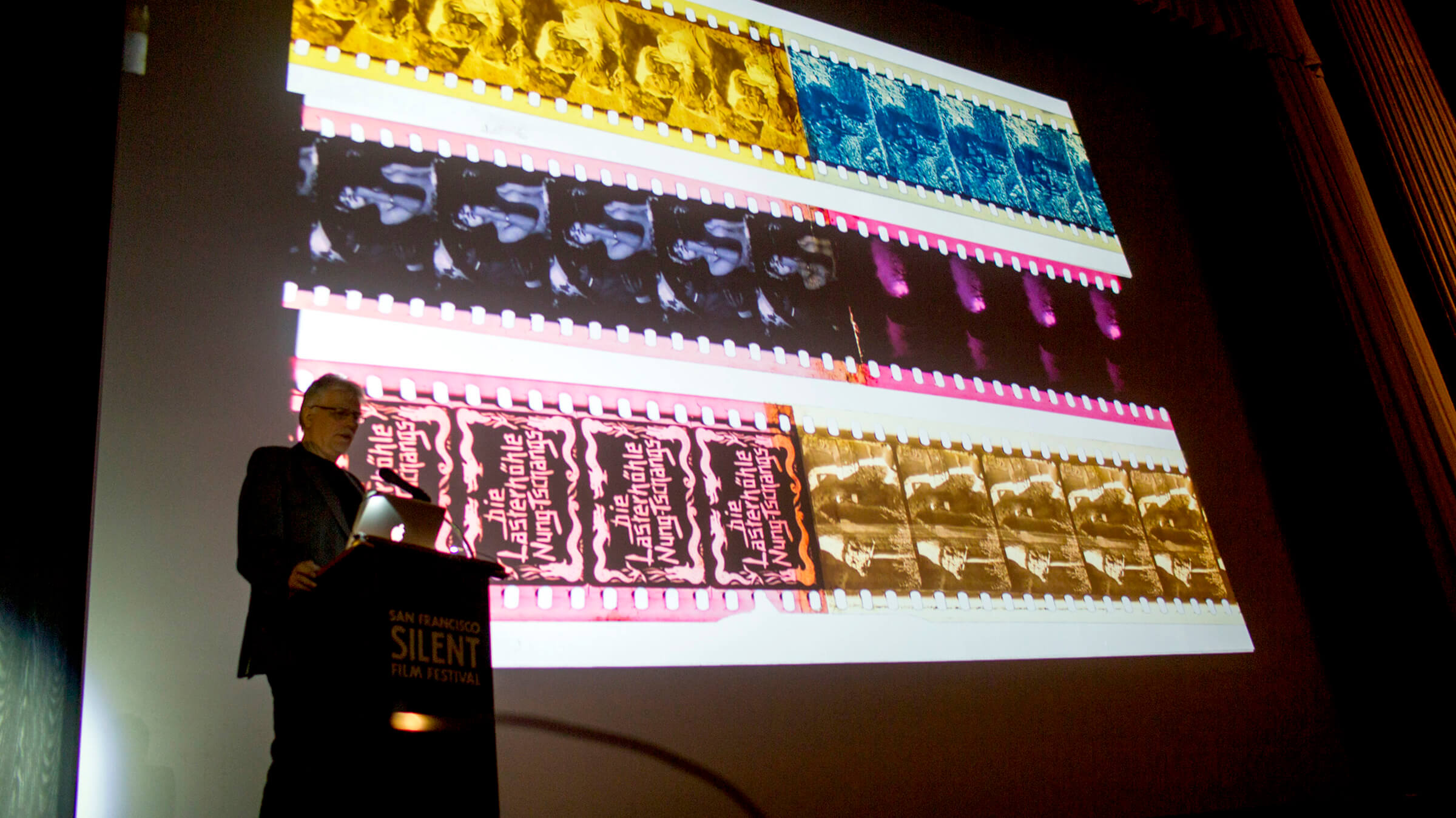

I was planning a Brigitte Helm retrospective and Enno Patalas recommended showing the beautiful 35mm print he just had acquired from Gosfilmofond in Moscow. I was thrilled, because it was not easy to get one of these unique prints from his Munich Filmmuseum collection. Since the Russian print had only Russian intertitles, I looked for a German title list from a 16mm print which was shown on television. These were not the original intertitles, but ones retranslated from a Danish print. Since these titles didn’t fit the print from Patalas, I realized that the 16mm print had parts that were missing from the Russian print. For the Helm series, we finally did the show as a kind of live reconstruction, switching between the 16mm and the 35mm projectors. In 1999, when I became director of the Munich Filmmuseum, I discovered that just before his retirement Patalas had ordered a 35mm print from the Danish Film Institute. Since neither the original negative of Alraune nor the censorship card with the wording of the original titles is known to exist, we just combined the material of the two prints. Fortunately, the Russians cut out different scenes than the Danes cut out. In 2019, about twenty years later, we found some of Henrik Galeen’s personal papers, including the second half of his original Alraune screenplay. With this, and an intense study of all the contemporary reviews and censorship files, we started a new digital restoration.

In what ways does it still differ from the original?

All the reviews mentioned the performance of Valeska Gert, a notorious dancer in Berlin. It was a short scene in the first reel, just one or two minutes. She dances in front of a bordello with a Black soldier. This was too taboo and was cut out everywhere by the censors. The scene is still missing, but at least I found a photo in an old film program which is now in the movie. I also found in reviews that the film was tinted. The Danish print had some tints, but usually Danish tints were different from German tints. I modified them a bit based on how German tints were done in those years. But the biggest problem was always the first reel—the origins of Brigitte Helm’s character. In some countries, the film started only with the second reel, when Alraune is already seventeen years old. But now it is nearly complete.

Did this film have an original score?

In Germany, there were only a few dozen films for which an original score was written. It was quite common for the musical director of each theater to compile music for films in a very short time. It differed from theater to theater. Alraune was very successful, based as it was on the best-selling novel, but it was not such a big production that a known composer was hired. So, we had to have new music. For me, it’s always very important that the films get appropriate music. Especially when certain passages are missing and I have to put in photos or explanation titles for bridging the gap, I very often do it in close collaboration with a musician. The music catches the emotional spirit of a scene better that I can do. For me a film restoration doesn’t mean just to preserve what I found. My aim is to restore a film as close as possible to its premiere version. And to present it on screen to an audience—the magical moment that makes all the effort worthwhile.