Julien Duvivier is the forgotten man of French cinema. Prolific and bad-tempered, nicknamed “Julien-le-mal-aimé” (Julien the unloved), he careened from genre to genre, making thrillers, noirs, comedies, melodramas, and religious films during an almost fifty-year career of nonstop film production, leaving behind nearly seventy films when he died in 1967 after wrapping the tepid thriller, Diabolically Yours. By then his reputation was already in the toilet; the Cahiers du Cinéma crowd had trashed him as an outmoded, commercial hack in the 1950s, using Duvivier’s genre-hopping and prodigious output as evidence that he lacked an auteur’s vision.

How quickly audiences forget. Travel back in time to 1929 when Duvivier made The Divine Voyage (La Divine Croisière) and we find critics calling him “one of the top French directors,” an assessment that journalists echoed for the next decade or so as Duvivier made classics like Pépé le Moko and was fêted, honored, and interviewed. His renown reached Hollywood, where he was invited to direct in 1938 by MGM on the strength of his recent hit Un Carnet de Bal, and where he returned to make movies as a World War II refugee. At a party in Duvivier’s honor during his first visit to Hollywood, King Vidor called him “a director in the proper sense of the term; you see his stamp on all his productions.” Take that Cahiers!

The mal-aimé director has since made a posthumous comeback. Prompted by screenings marking his one hundredth birthday, biographers and historians began to re-evaluate Duvivier’s films; The Divine Voyage, in particular, is ready for its close-up. Long believed lost, the rediscovered Voyage, with its unusual combination of religion and rabble-rousing, is an often overlooked entry in the crowded field of Duvivier silents: nineteen films in eleven years, three in 1929 alone. Critics tend to gravitate toward the audience-pleasing pathos of Poil de Carotte (1925), Duvivier’s personal favorite of his silent era work, or the jazzy pyrotechnics of his final silent, Au Bonheur des Dames (1930). Yet in many ways Voyage is classic Duvivier: assembled with technical mastery, peppered with extravagant plot twists, its sentimental storyline mined with casual cruelty.

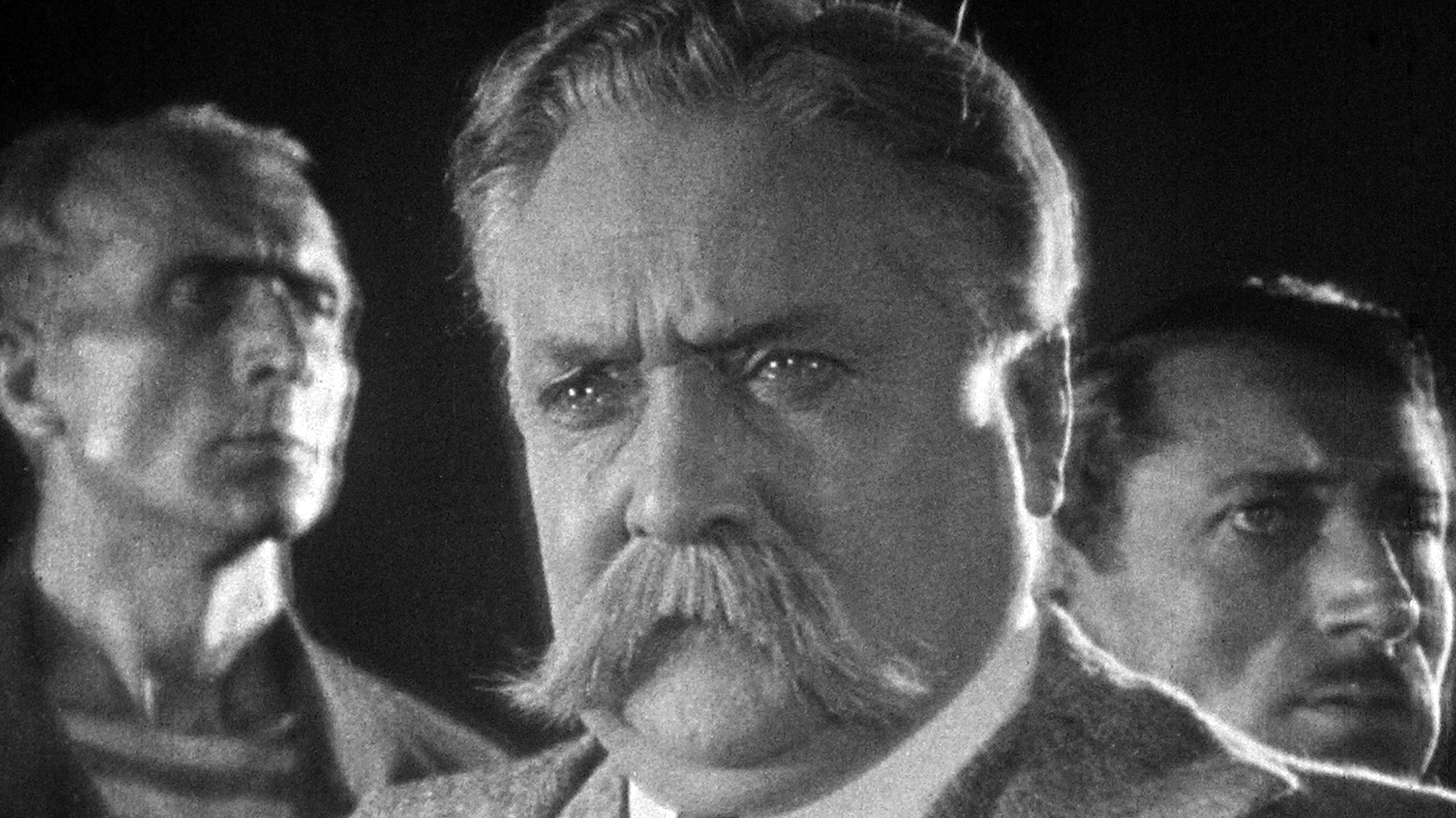

The film starts with a literal bang: the barrel of a gun rises up over a windowsill, and we are immediately plunged into the action. Rich and powerful Ferjac (Henry Krauss) is an unscrupulous shipowner who tyrannizes his seaside Breton village and is both resented and feared by the villagers. The failed assassination attempt interrupts a meeting between Ferjac and a delegation of sailors who refuse to set sail in his dilapidated vessel, La Cordillière. Accompanying them as intermediary is the poor but aristocratic captain, Jacques de Saint-Ermont (Jean Murat), who is (of course!) in love with Ferjac’s daughter Simone (Belgian star Suzanne Christy), a saintly antithesis to her cruel father. Ferjac ruthlessly quashes the sailors’ nascent rebellion: “You really want to starve?” he sneers.

Duvivier wrote the scenario, smuggling a critique of capitalism into an overstuffed, but nonetheless wildly entertaining melodrama on the power of faith, a theme he explored in several films, both silent and sound. This eclectic excess was exactly what Duvivier’s later detractors disliked about his films, but the energy of Duvivier’s camera and cutting make it work, all of it—subplots featuring orphans and kindly priests, forced engagements, murder, mutiny, and a visitation from the Virgin Mary. Historian Noël Herpe has pointed out Duvivier’s fondness for escalating plot tensions into not one but a series of climaxes—the more the better. In Divine Voyage he splits the narrative into two, cross-cutting between the mariners’ perilous voyage and the bubbling rebellion of the villagers back on land. This dual narrative allows the director two of everything—two frenzied battles between opposing sides, two fires, two reunions. It’s a narrative strategy that looks forward to the “sketch” films Duvivier became known for like Carnet du Bal (1937) and Flesh and Fantasy (1942), multiple stories with a loose framing device.

Filmmaking was Duvivier’s second choice after an unsuccessful attempt at theater acting. Once he made the switch, however, he gave the new medium his all. He served as assistant to André Antoine on several productions and made his first film, Haceldama or the Price of Blood, in 1919. Then twenty-three, the novice director also wrote and sometimes shot (his camera operator was busy keeping the location electricity flowing). “Not only did we make the film but we developed it,” Duvivier reminisced later. “It was a heroic epoch.” Historian Lenny Borger called Haceldama “one of the most dismal debuts by a great director,” but trying things and making mistakes was part of Duvivier’s process. Throughout his career he experimented, and also stole from those he admired—first Eisenstein’s editing and Jean Epstein’s superimpositions, then later trading cast, crew, and technique with Orson Welles.

By 1925 Duvivier had blended what he borrowed into his own style. He favored location shooting like Antoine did, and in 1924 he even used hidden cameras to capture his actors mingling with crowds of the faithful at Lourdes for Credo, or the Tragedy of Lourdes. In the summer of 1928 Voyage’s cast and crew traveled to Paimpol in Brittany, where Duvivier shot in swamps and aboard ship while camera operator Thirard hiccuped with seasickness as he cranked the camera. Yet Duvivier also embraced artifice, telling a journalist that the best storms were made in the convenience of the studio. He was an enthusiast of the Hall process, the use of painted plywood cutouts placed in front of the camera to augment a set or location. For Voyage’s climactic fire scene, Duvivier combined location and artifice, “planting” a forest of logs on Ermenonville’s sands and then burning it down while locals watched.

Duvivier uses all these tools and more to create stunning sequences in The Divine Voyage that still pack an emotional wallop today. In one scene angry villagers invade Ferjac’s chateau where he’s hosting a grand celebration of his daughter’s engagement. The confrontation unfolds organically, stopping and stalling, as Duvivier cuts fluidly between different angles, rhythmically mixing wide and tight shots. The traveling shot was a Duvivier hallmark, and here the camera glides the length of the lavishly set table and even seems to briefly float over the action. Some guests retreat from the conflict, while others advance to confront the villagers, who hesitate as well, until the camera goes tight on Ferjac as he swipes off a villager’s cap—and the battle is on. The film is full of vivid imagery, from the shadowed close-ups of the craggy-faced Bretons, to the black silhouette of a man emerging from a white cloud of smoke, and the Busby Berkeley-esque overhead shot of a sailor spinning within a circle of white-coiffed women, all trying to embrace him at once.

Much has been made of Duvivier’s faith, or his loss of it. Even his films with no overt religious content routinely depict falls from grace and crucifixions with no resurrection, as in 1946’s Panique. Ultimately his films (comedies included) focus on the cruelty of human nature, the many ways humans have for screwing each other over. It’s a misanthropic, misogynistic, melancholy, bleak worldview, one that critics sometimes blame on his grim childhood, his Catholicism, or both. “I know it is much easier to make films that are poetic, sweet, charming, and beautifully photographed,” Duvivier once said, “but my nature pushes me towards harsh, dark and bitter material.” Whatever the roots of this attraction, the result is Duvivier’s reputation as “cinéaste du noirceur,” the filmmaker of darkness.

The Divine Voyage both reinforces and complicates this reputation. While in his bleakest film, Panique, Duvivier pits the lone outsider against the ignorant and vicious crowd, in Voyage, the dynamic is reversed; the close-knit Breton community rebels against lone tyrants like Kerjac and the bullying mutinous sailor Mareuil. Most significantly, in Voyage the villagers prevail, the lost sailors return. The moment when Kerjac falls to his knees and bares his head provides genuine catharsis and a rare glimpse of Duvivier’s closeted optimism. Noël Herpe calls Duvivier “a tender soul who distrusted tenderness.” Watching The Divine Voyage we catch Duvivier before the distrust and darkness completely descend.

Presented at SFSFF 2022 with live musical accompaniment by Guenter Buchwald and Frank Bockius