Deliciously weird for 1919 or any other year, Ernst Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (The Doll) declares its intent to please from the first shot. An appealing twenty-seven-year-old Lubitsch himself is the first person to appear, as he refuses to look his own camera in the eye. Instead, from a toy box he busily assembles a cute little diorama composed of a felt lawn and an S-curved driveway, a series of cutout trees on pencil-size trunks, and a house with one door, one window, and a removable roof. He opens the house, places two dolls inside, and presto—the story begins. Our director is the doll-maker’s doll-maker, E.T.A. Hoffman with a camera, manipulating the characters for all they are worth.

Lubitsch made seven movies that year, as his career roared into high gear and his comic vision took shape. Born in Berlin in 1892, he began as a comic actor playing ethnic roles, often as a Jewish character named Meyer. He was a good actor, but Lubitsch gradually discovered that he was an even better writer and director. He’d made his mark as a “serious” director only the year before, with an exotic Egyptian horror outing called Die Augen der Mumie Ma (The Eyes of the Mummy Ma) starring Pola Negri. Thereafter Lubitsch’s time in Berlin was somewhat oddly divided between lush historical dramas such as Madame Dubarry, with the heavy-breathing duo of Negri and Emil Jannings, and comedies, of which The Doll is an enchanting example.

Written by Lubitsch and frequent collaborator Hanns Kräly, from the same Hoffmann story that gave us the ballet Coppélia, this fairy tale has even less truck with dreary reality than the all-dancing version. Made at Germany’s Ufa the year before The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The Doll unfolds like a mad picture-book come to life. The backdrops are mostly forced perspective, full of slanted picture frames and out-of-scale doorways. One character’s kitchen has the hanging pots and pans painted straight onto the flats. A carriage arrives pulled by two horses that are actually four men in vaudeville-style horse costumes. When one of the string tails falls off, the coachman casually sticks it right back where it belongs. The sun and moon are embodied by paper cutouts with faces—the movie often looks as though it were designed by a precocious seven-year-old.

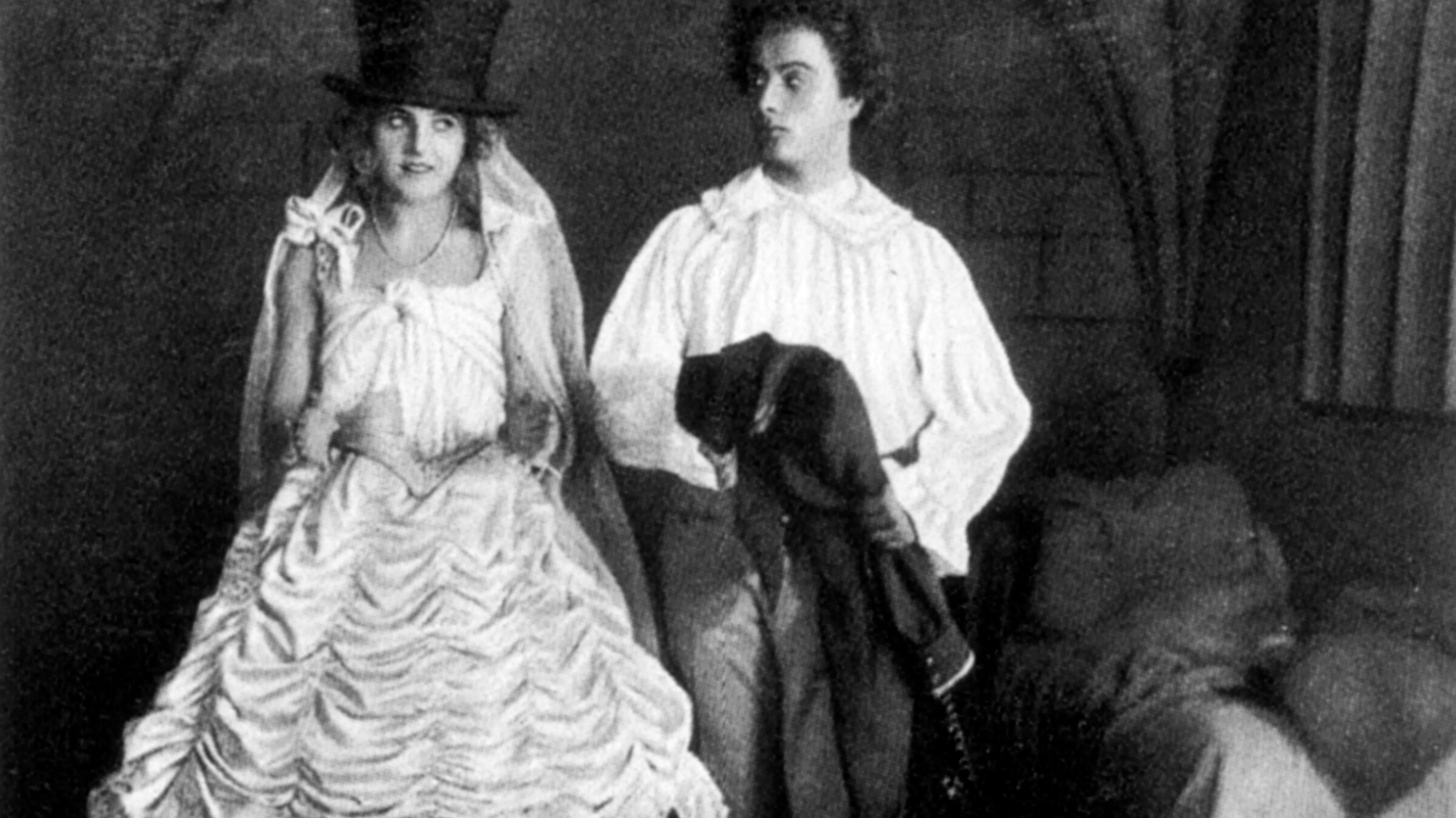

The jokes, however, are not necessarily for children. The Doll is essentially a sex comedy, about an effete young man who tries to marry a mechanical doll, only to discover that she’s flesh and blood, and more fun that way. The protagonist (he is in no sense a hero) is Lancelot, played by Hermann Thimig with a series of ill-fitting frock coats, a Percy Shelley coiffure, and a personality firmly under the thumb of his mother.

Lancelot is the heir to the family name and his uncle’s fortune, which is all right, but that also means he must marry and have little Lancelots, a prospect that fills him with whimpering horror. His uncle, the Baron of Chanterelle (Max Kronert), opts for marital shock therapy, by offering an enormous dowry and inviting all the maids of the village to come to the town square so that one may be chosen. This unnerves Lancelot to the point that he jumps out the window and, pursued by peasant lasses who foreshadow the vast bridal mob in Buster Keaton’s Seven Chances, runs like hell, back and forth across the frame.

Eventually Lancelot must hide, and where else to escape feminine clutches but in a monastery. The one he chooses is occupied by monks who keep up their spirits and stout figures with a steady diet of pork, which they are at first reluctant to share. But then they hear of the money involved and come up with a scheme: Lancelot can keep them all in pig knuckles simply by marrying a doll. And lo, the nearby village features Hilarius (Victor Janson), a maker of lifelike mechanical dolls, “offered,” as his advertisement states, “to bachelors, widowers, and misogynists!”

Here the film takes flight, when we meet Ossi, played by Ossi Oswalda: daughter to Hilarius, model for his latest creation, and soon-to-be human substitute for a broken doll. Petite, charming Oswalda was sometimes called “the German Mary Pickford,” although she had a far more unruly mane of blonde hair, and more of a hint of sex. Lubitsch also used Oswalda’s sprite-like talents in I Don’t Want to Be a Man in 1918 and The Oyster Princess later in 1919. Scott Eyman, in his Lubitsch biography, suggests that she may have had a crush on her director, but nothing came of it. Be that as it may, they work marvelously well together. Oswalda’s joyous energy is, quite deliberately, the most natural element of the film.

Jokes and emotions dash across Oswalda’s big-eyed face like Mack Sennett actors. Her goofy allure has ensnared her father’s adolescent apprentice (Gerhard Ritterband), who necessitates the whole deception by trying to dance with Ossi’s mechanical replica and breaking the thing’s arm in the process. When her temporary masquerade as the doll turns into an elopement, her alarm lasts only a few minutes. By the time she’s in the carriage headed for the wedding, Ossi is back to finding the situation irresistibly funny and amuses herself by falling against her reluctant groom a few times. The wedding itself brings an impressive demonstration of her mime abilities, especially in a scene where she is trying to sneak some food. She chews, Lancelot looks, she stops; he looks away, she chews again, he checks again, and again, faster and faster.

Eventually, of course, the deception must be unmasked, and in the marriage bed (although safely on top of the covers—as ever, Lubitsch didn’t need the explicit), Lancelot discovers he likes girls after all, and Ossi is happy to help, at least for now. The thought occurs that a woman so adept at deception will have no trouble finding a solution if Lancelot turns out to be a boring husband.

When he arrived in Hollywood in 1921 to make a movie for Mary Pickford, Lubitsch was asked to name his favorite of his films; he answered The Doll. As Eyman points out, even toward the end of his life, he cited the movie as one of the best he had made in Germany. The Doll is a young man’s picture, fast-moving, bursting with energy and carefree experimentation, its jokes ranging from sophisticated winks to groaning eye-rollers. The bizarrely suggestive intertitles pile up: “Familiarize yourself with the mechanism,” Hilarius admonishes Lancelot about his doll-wife, along with later instructions to “Always dust her well” and “don’t forget to oil her every two weeks.” Lubitsch was already using a skill he would perfect in Hollywood: risqué, but deniable.

Presented at SFSFF 2017 with live music by Guenter Buchwald and Frank Bockius