From the Lumières’ point-and-shoot street scenes to Méliès’s fantastical trick films, from the thrilling serials of Feuillade to the foible-filled folly of Max Linder, French filmmakers enthralled global audiences with the worlds they created on-screen. But then the war came and German and American productions vanquished not just French exports but the home market as well. Into this void stepped artists with a new language and a new purpose, to create what they called “pure cinema.”

A recurring beef among critics and these new filmmakers was French cinema’s reliance on theater and literature, not only for content but form. In 1921, Jean Epstein described the national cinema as nothing more than “albums of poses and catalogues of décor.” When Abel Gance’s La Roue plowed onto screens in 1923, critics loved its kinetic rhythms (a camera was mounted on the wheels of a train, among other moving places) and saw in it a new path for narrative filmmaking. Young journalist and budding director René Clair mostly agreed but thought the film had not gone far enough, relying too much on the written word: “Oh if Mr. Abel Gance would only give up making locomotives saying yes and no, lending a railroad engineer thoughts of a hero of antiquity and quoting his favorite authors … Oh, if he were willing to give up literature and place his trust in the cinema!”

By the time he directed The Italian Straw Hat, Clair had put his complete trust in film’s visual language, a trust he had developed over a scant five years, first writing about cinema then making it. According to Celia McGerr’s biography of the director, in 1920 singer Damia “persuaded a reluctant Clair to play the role of a suave Parisian in Loie Fuller’s poetic film on dance, Le lys de la vie, by telling him about the pretty girls who would be present.” He appeared in two Feuillade films and became an assistant to director Jacques de Baroncelli. He met Diamant-Berger, a director and producer then operating his own studio who made possible Clair’s short film about a powerful ray that zaps almost all of Paris asleep in Paris qui dort, a storyline conceived, says film historian Allan Williams, in an opium-induced stupor. In 1924, Clair collaborated with painter Francis Picabia and composer Erik Satie on the short film Entr’acte for a Dadaist night out at the Ballets suédois.

He moved on to fantastical narratives, Le Fantôme du Moulin Rouge and Le Voyage imaginaire, which combine whimsy with gentle social satire while employing the tricks and techniques of his experimental work. Clair was taken, too, with the narrative economy and dazzling special effects of American motion pictures. “How in the hell did they do that, make Douglas [Fairbanks] fly about on the magic carpet, for example? I spent weeks trying to figure it out.” He recognized the limits of American industrial production, writing that Hollywood’s inventiveness with camera angles “seemed to have stopped short in fear of what still remained to be discovered.” Still, he routinely took his fellow Frenchmen to task for what he judged a neglect of a storyline. Even his favorable review of Coeur fidèle, for which Epstein strapped a camera to a twirling merry-go-round, one of what Clair called “surprising angles,” criticized the film for going “astray into technical experiments, which the action does not demand.”

When producer Alexandre Kamenka went looking to replace the Russian émigré filmmakers recently defected to another Parisian outfit, he found several obliging locals with pure cinema aspirations willing to dedicate themselves to story. Marcel L’Herbier, Epstein, and Clair (along with Jacques Feyder) became the names associated with France’s late silent-era. Clair’s La Proie du vent, adapted from a 1926 novel, did well with the public but he later dismissed it as proof he “could make a commercial film as bad as everyone else’s.” It’s valuable enough, however, as the film that allowed him to make Italian Straw Hat.

In what might seem like a contradiction of his pure cinema stance, Clair chose a play from the previous century for his second Albatros outing, Eugène Labiche’s most popular boulevard burlesque (Un Chapeau de paille d’Italie, written with Marc Michel), about a bridegroom whose wedding day is complicated by a straw hat. In a 1979 interview, an eighty-year-old Clair described how he prepared to transform the material for film: “After I accepted the idea of a play or a novel, the first thing I did was to close the book and not to look at it anymore.”

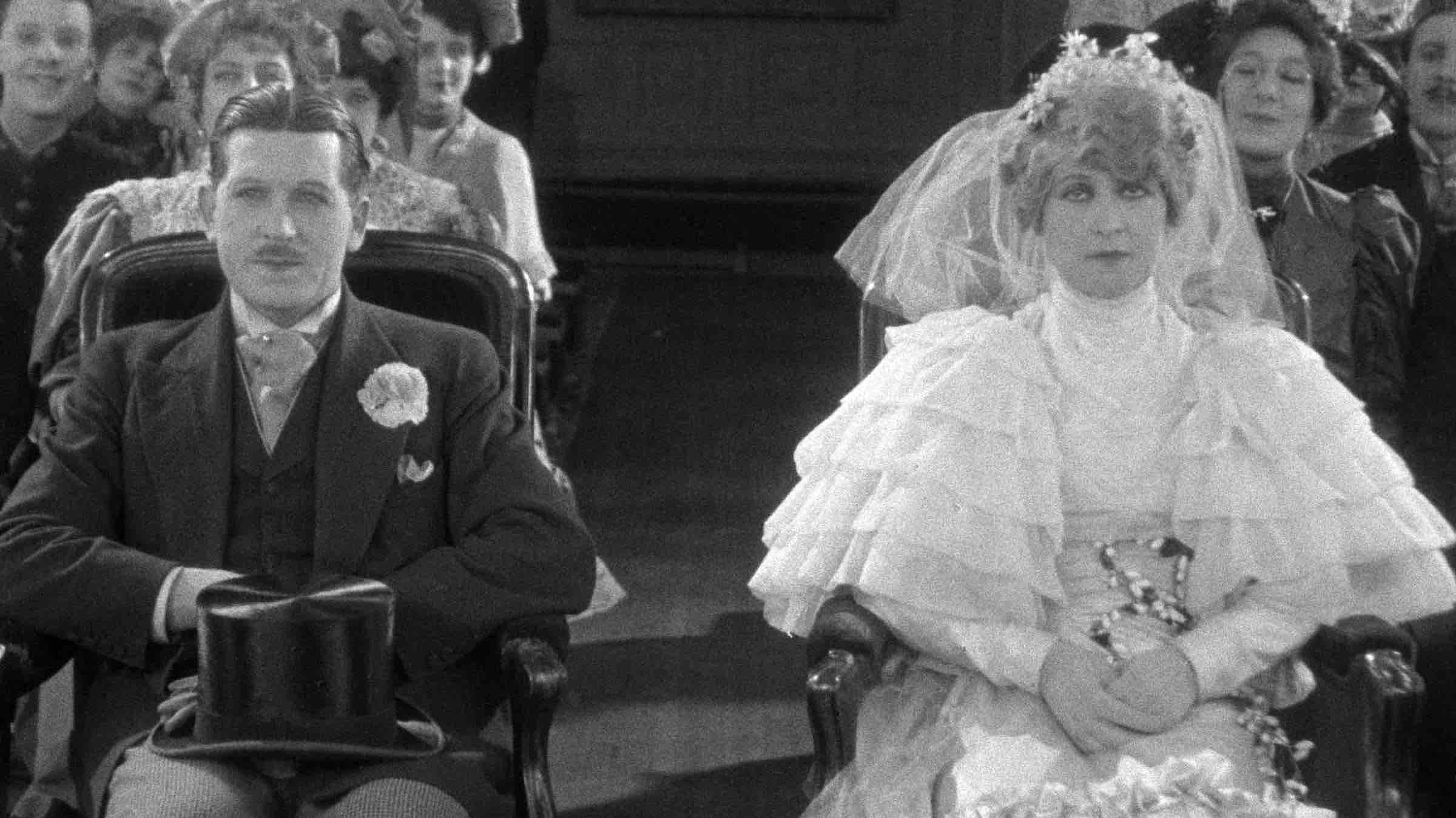

With the expert help of Albatros resident set designer Lazare Meerson, he lovingly recreated the era in which cinema was born, transforming the mid-nineteenth century setting to the Belle Époque and paying homage to one of the French cinema greats, Max Linder, in the form of a tuxedoed leading man (Albert Préjean) as a decorous gentleman beset by increasingly absurd circumstances on his wedding day after his horse chomps the wrong lady’s hat. Préjean is joined by a stellar cast of equals, Maryse Maïa as his longsuffering bride who endures her groom’s perplexing new behaviors, Russian-born Olga Chekhova, in a drooping artichoke of a dress repeatedly fainting into the arms of a succession of men, and Vital Geymond whose buttoned-down chest heaves with his threat to break every stick of furniture in the groom’s newly furnished apartment unless restitution is made for said hat. Intertitles are sparse, but no less entertaining, and one tersely explaining the gravity of Chekhova’s condition will elicit gales of laughter.

Everyone has a sartorial irritant to overcome, a test to their Sunday-best dignity: a stray pin, tight dress shoes, a missing glove—a pesky tie becomes a running joke that gives generously time and again. The supporting players hold up their end splendidly: Paul Ollivier as the hard-of-hearing uncle with his malfunctioning ear horn, Jim Gérald as the rotund cuckold, and Alice Tissot and Alexis Bondireff as a couple whose years of marriage have not improved the legibility of their secret sign language. Valentine Tessier (Jean Renoir’s Madame Bovary in 1933) as a lady shopper in a boldly striped dress has a few moments of exquisite exasperation as men invade a domain heretofore restricted to ladies. The camera is employed in only a few “surprising” angles, once on the dance floor when the groom’s frustrated quest has him spinning nearly out of control.

Italian Straw Hat has been heralded since its release as a gem. Edmond Epardaud wrote that “René Clair founded a new genre” and, in 1929, Charles de St. Cyr called it a “comic masterpiece of French cinema.” The Museum of Modern Art’s Iris Barry observed in 1940 about the film’s rich saturation in nostalgia, “scene after scene painstakingly and brilliantly captures the very atmosphere and flavor of pictures taken 30 years earlier, as when the Lumière employees walked out of their factory at lunch-time and were eternally caught and recorded by the motion picture in a sunlit moment of time.” It stood up thirty years later when Pauline Kael called it “very simply one of the funniest films ever made.”

That it does not appear on Best Film Ever lists alongside The General, Sunrise, Man With a Movie Camera, etc., can only be an oversight that will surely be corrected as soon as this new restoration, showing off the beautiful photography (by Maurice Desfassiaux and Nicolas Roudakoff) and lush sepia tinting, makes the critical rounds. As tightly choreographed and as keenly attuned to subtle expression and gesture as any Buster Keaton film, it, like the best Keatons, delivers much more than laughs.

Presented at SFSFF 2016 with live music by the Guenter Buchwald Ensemble

***