The now-forgotten expression “clothes maketh the man” dates to the Middle Ages, but it seems to echo loudest from the early twentieth century when office jobs multiplied in new skyscrapers and country folk migrated to the cities by the tens of thousands. It could have been coined to describe the doorman of the upscale Berlin hotel in The Last Laugh (Der letzte Mann), whose authority, status, and self-worth derive not from his character or accomplishments but from his position, represented by an overcoat bristling with buttons.

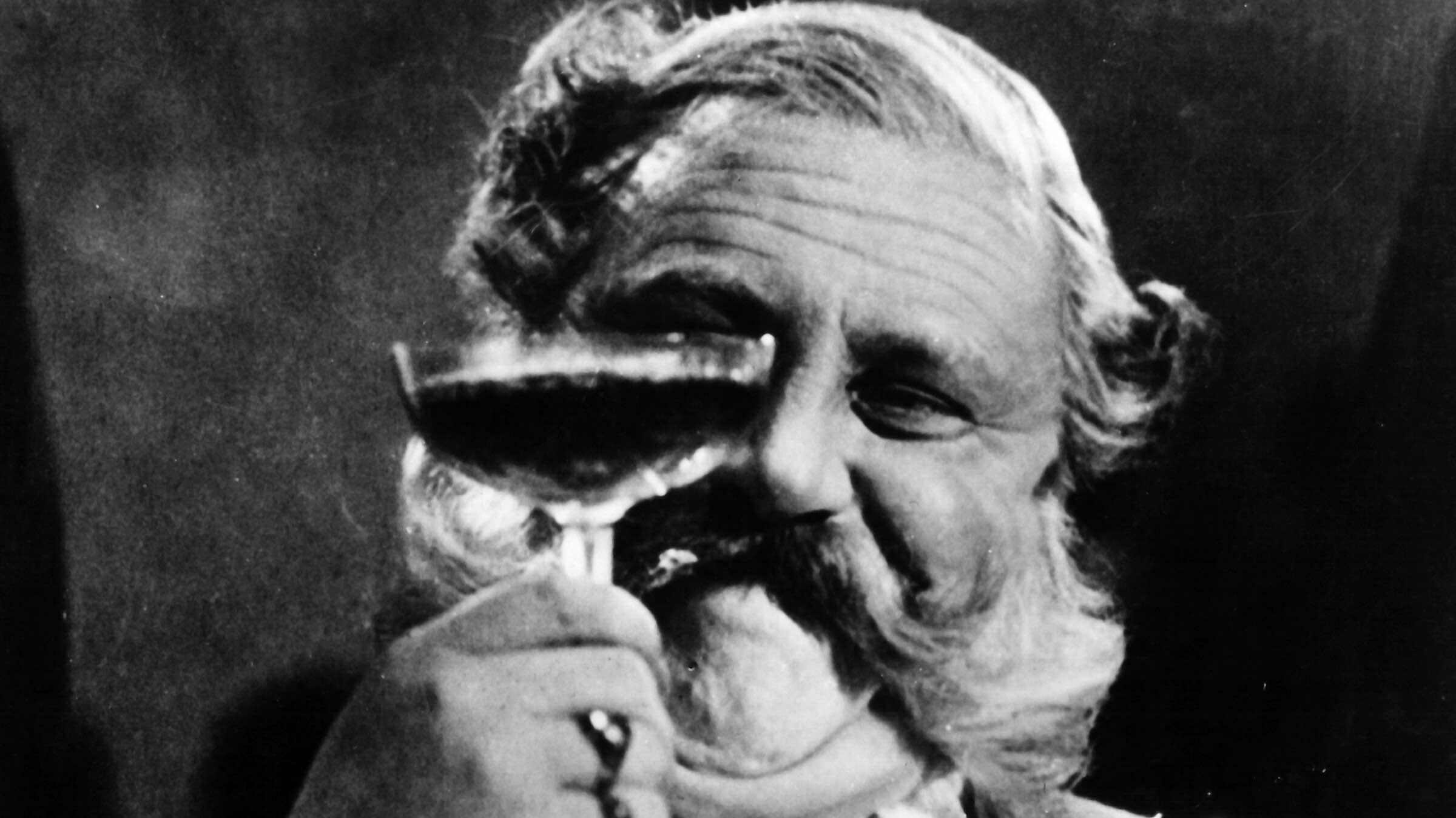

Women supposedly love a man in uniform, and so does everyone else in this pompous fellow’s tenement neighborhood. Actually, “love” is not the correct word for the tumble of emotions that the doorman (a hulk portrayed by the imperious, larger-than-life Emil Jannings) provokes, for pride and reflected glory will eventually give way to contempt and resentment. For now, his daily brush with the affluent, the aristocracy, and captains of industry sets him apart and above his neighbors; it also offers them a smidgen of faith that the job their children get toiling for the “1%” just might be in a swanky spot. Hope is the not-so-secret ingredient in capitalism.

But one day, after many years of loyal service, the Atlantic Hotel demotes the front doorman to lowly lavatory attendant. (Ostensibly he has grown too old to carry luggage. But as that stickler for station Fritz Lang observed, no doorman would lower himself to doing the work of a porter or valet.) With the reclamation of the doorman’s impressive, button-bedecked regalia, his dominance evaporates. Housekeeping giveth, and Housekeeping taketh away. Alas and at last, our man is revealed as an empty suit.

Screenwriter Carl Mayer’s beautifully conceived fable locates its emotional heart in the poignant figure of a working-class man who, after many years on the job, inevitably forgot that his authority was temporary. It was granted to him by the true keeper of the keys, the hotel owner, and now it has been withdrawn. Any perks beyond a living wage that Jannings’s character enjoyed for all those years were illusory. And he is as devastated as anyone whose illusions have been shattered.

Mayer’s worldview encompasses class consciousness and more—an awareness that the Great War marked the beginning of the end of an era. After all the pointless loss and sacrifice and heroism, the spit-shined military officer had lost his luster. Specifically, the war exposed the nepotism, privilege, and backward incompetence of the officer class, and the unfairness of a system that rewarded ancestry rather than accomplishment. The public (in Germany, England, and elsewhere) finally figured out that the officer’s uniform, in and of itself, did not denote or bequeath character. The doorman’s acquaintances sensed it all along, and The Last Laugh was a subtle nudge in the ribs for moviegoers in 1924.

Emil Jannings was a massive monument as well as a major star in Germany, and the screenwriter Carl Mayer, the cameraman Karl Freund, and the director F.W. Murnau devised a fluid, kinetic film to situate him. While Murnau (Sunrise) is acknowledged as a genius and Freund came to be revered in Hollywood as an innovator (in addition to photographing the ending of All Quiet on the Western Front, he won an Academy Award for The Good Earth and received a Technical Oscar in 1954), Mayer is less appreciated.

Unlike the modern screenwriter, who is discouraged by producers and scriptwriting software alike from including shot descriptions and camera angles, Mayer wrote remarkably detailed blueprints that provided cinematographers, set designers, and even directors with a distinct vision. The Austrian native, whose first screenplay was the German expressionist milestone The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (another allegory of the aftermath of WWI, cowritten with Hans Janowitz), had a profound understanding of cinema’s special ability to convey psychological states. He believed “the movement of the camera … should convey the vertigo human beings experience when trying to come to terms with their environment.”

Mayer was a true pioneer of cinema; he thought, saw, and created stories in the grammar of film. He imagined and invented compositions and effects that the other key talent had to figure out how to achieve. For artists like Freund and Murnau, that was the best kind of challenge.

Freund recalled in a 1947 interview for “A Tribute to Carl Mayer,” a pamphlet published after the screenwriter’s death at forty-nine from cancer: “For the well-known trumpet shot, we suspended the camera in a basket from a bridge that ran the length of the courtyard, and when we found that our pulley could not haul the basket upwards the way we wanted, we shot the scene downwards—and reversed the film in the camera. When we wanted to show Jannings drunk, I strapped the camera to my chest, with batteries on my back for balance, and acted drunk … Mayer’s imagination had convinced us that we could do anything!” Last Laugh producer Erich Pommer once summed up his genius, “Carl Mayer writes true film scripts.”

The writer Kenneth White observed in a 1931 article for the Harvard-based Hound and Horn, “The doorman got drunk, but not in the way a pantomimic actor with subordinate properties got drunk; the camera did it for him.” Those who enjoy the notion that cinema endlessly repeats and reinvents itself in different places and contexts can draw a mostly straight line to certain contemporary directors who prefer directing computer-generated images than actors.

The degree to which Mayer thought out his scenarios, and the level of brilliance sparked by his collaboration with Murnau and Freund, is reflected in the near-absence of title cards in The Last Laugh. It was the unchaining of the camera, however, that galvanized the American movie industry and eventually brought all three men to Los Angeles.

After the first screening of The Last Laugh in America, “There was a telegram from Hollywood asking what camera we had used to shoot the film,” assistant cameraman Robert Baberske recalled. “The Americans, used to a precise technique, didn’t dream that we had discovered new methods with only the most primitive methods at our disposal.”

Freund and Mayer were two imports whom Hollywood, thankfully, didn’t corrupt. Among their subsequent credits, with Baberske and cinematographer Walter Ruttmann, they made Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (1927), a gorgeous and still-astonishing pinnacle of experiential, visual, and nonverbal cinema.

Presented at SFSFF 2015 with live music by the Berklee Silent Film Orchestra

Berklee College of Music composers: Xiaoshu Chen, Amit Cohen, Emily Joseph, Eiji Mitsuta, Shotaro Shima, and Gabriel Torrado