She swore that she hadn’t meant to kill him that New Year’s Eve of 1915. Gabrielle Darley had brought the pistol along for self-defense and it had been tucked in her fur muff when it fired the fatal shot into her lover, Leonard Topp. Her defense attorney, Earl Rogers, offered up a hole in the muff as evidence. The prosecutor saw it differently and declared, “If that isn’t a moth hole, I’ll eat the muff!” Rogers objected on the grounds that the prosecutor had failed to offer evidence that he had ever actually eaten a muff. The spectators giggled, the jury smiled, and the case continued. Darley was acquitted after a deliberation of just eight minutes. As a trial-as-entertainment, it had been a masterpiece.

As Darley told it, she was a naïve waitress barely out of her teens when she fell under the power of Topp, the charming bounder who promised to make her his bride but was merely interested in being her mack. If it sounds familiar, it was a tale that could have been stolen from the intertitles of any number of white slavery films that were doing big business at the time. A free woman after the verdict, Darley was whisked away to the home of famous singer and philanthropist Lark Ellen, whom Rogers had invited to the trial to prove to the jury that the smart set sided with Darley.

Years passed but one courtroom spectator was instrumental in returning Darley to the public eye. The defense attorney’s daughter, Adela Rogers St. Johns, continued the story in the November 1924 issue of Smart Set magazine. “Gabrielle of the Red Kimono” sculpted post-trial Darley into a Magdalene-like figure of woe, used and abused by society and offered no escape from the life that had led to her tearful murder of her lover. It was a story made for the movies—if the censors would allow it.

Dorothy Davenport found Darley’s tale ideal for her cinematic brand. Her early widowhood, the result of her husband Wallace Reid’s tragic drug-related death, had inspired her to go behind the camera in order to champion social issues under the banner of Mrs. Wallace Reid Productions. Her biggest hit, the antidrug film Human Wreckage, is now lost but it provided a blueprint for bringing the story to the screen. Her two-pronged goal was to make movies that both entertained and educated and, if they grabbed headlines, so much the better.

The film version of the Darley story offers up numerous villains for Gabrielle to contend with, but the main antagonists are phony philanthropists, specifically the Lark Ellen figure here renamed Mrs. Fontaine. Reformers were among the great recurring villains of the silent era, ready to snatch infants from their mothers’ bosoms (Bonner contends with them again as a single mom in It) and expose the darkest secrets of fragile waifs who were then turned out into blizzards. In The Red Kimona, these reformers are given another layer: cattiness. Gabrielle is there to provide them with salacious details so that they can revel in the sin while simultaneously condemning it. Red Kimona scenarist Dorothy Arzner later directed Dance, Girl, Dance, which featured burlesque dancer Maureen O’Hara giving similarly smirking high hats the lecture of a lifetime.

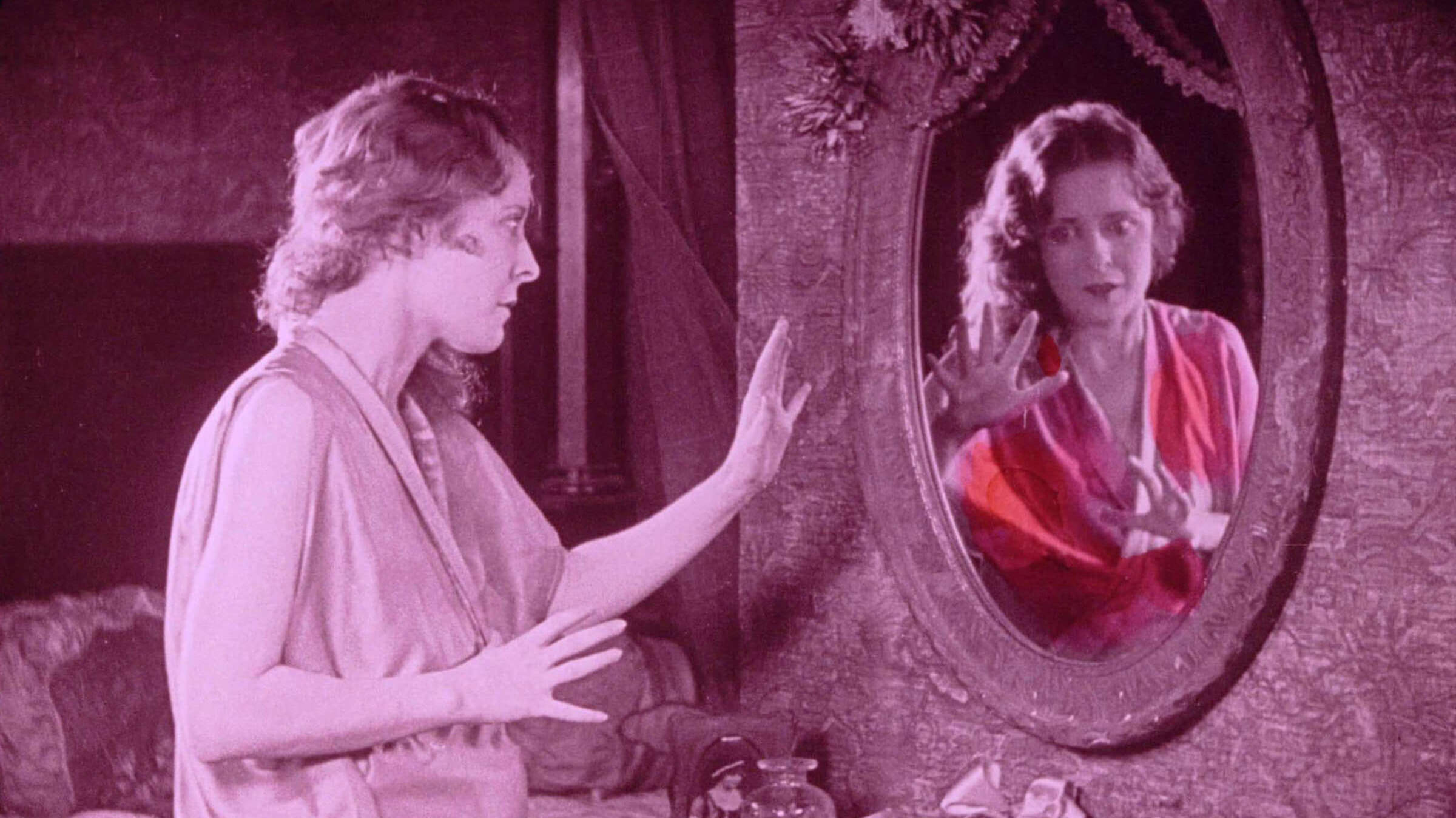

Both Arzner’s script and the final film are careful to omit any hint of spiciness during the scenes showing Gabrielle’s life as a prostitute and instead focus on her despair. In other ways, though, the picture is upfront to the point of bluntness; both Gabrielle’s “kimona” and the streetlight in her New Orleans neighborhood are hand-tinted crimson, real cats lurk while the society matrons fish for lascivious details. One notable flourish is the rollercoaster ride enjoyed by Gabrielle and her only friend, Mrs. Fontaine’s chauffeur (played by Theodore Von Eltz). The camera is mounted to the car and the audience is taken along for the ride; unexpected twists and turns that mimic the experience Gabrielle has had in life so far.

Davenport and Arzner, like St. Johns in her short story, played down the theatricality of the 1915 trial and concerned themselves with the regeneration of Gabrielle Darley, specifically, the lack of a social safety net for women in Darley’s position and the need for women to be kind to their sisters in need. The titles, written by St. Johns, are an impassioned blend of religious pleading and social justice with a direct call to action: What would you do to save Gabrielle Darley? Davenport herself faces the camera, challenging the audience to answer. That challenge is amplified by Priscilla Bonner, who displays the kind of wide-eyed Gishiness that would be expected for the role, right down to being imperiled by George Siegmann. Her portrayal of Gabrielle is reserved, with a hesitant touch of hopefulness that is quickly smothered by an uncaring world.

While St. Johns’s story and the film billed themselves as absolutely factual, there were several significant tweaks in the material. Darley had lived and worked in Arizona but St. Johns moved the “crib” to New Orleans, a far more notorious locale at the time. The real Darley’s 1919 marriage to Bernard Melvin had been covered in the national press. “‘Girl of Woe’ Now a Bride!” blared one headline, followed by a description of the tearful reunion between the newly-minted Mrs. Melvin and her prison matron—but the matron is nowhere to be found when fictional Gabrielle comes around for help. Finally, America’s entry into the First World War figures into the film, and this was likely the reason why the main events of the story were moved forward in time from 1915 to 1917.

While Davenport set out to make entertainment, her film’s marketing was an uneasy blend of sensation and sex ed. “Packs a wallop! Fills the till!” screams one ad; no patrons under fifteen years of age admitted, whispers another. A screening in Pennsylvania advertised a lecture by a doctor to accompany the film. Filmgoers were assured that “this man will tell the truth about social hygiene and sex.” Censors were as scissor-happy as could be expected. Pennsylvania demanded twenty-five cuts and reshot titles, too, while the British Board of Film Censors banned the picture outright. The critical response was generally poor. Photoplay proclaimed it “something terrible” while The Film Daily advised, “Unless you run a grind show you had better forget this one.” Picture-Play was more tepid and said the picture was “supposed to stir you but misses fire.”

In “Gabrielle of the Red Kimono,” Adela Rogers St. Johns wrote that she did not know Darley’s whereabouts but that “if she should happen to read this story, perhaps she will know that every hand was not against her.” Whether or not Darley read that story, she certainly saw The Red Kimona. Davenport had taken the precaution of consulting both the judge and attorneys who had been involved in the Darley trial and studied the court record in order to avoid any hint of besmirching her protagonist. To protect the innocent and guilty alike, names were changed: Leonard Topp became Howard Blaine, Lark Ellen became Beverly Fontaine, but Gabrielle Darley remained Gabrielle Darley; this proved to be an expensive mistake.

Darley claimed that her reputation and blissful existence as a respectable wife had been damaged to the tune of $50,000, even as the movie had been sympathetic to Darley’s plight, a plea for her to be allowed to join polite society. Actually, that was the same argument put forward by the plaintiff in Melvin v. Reid. Wasn’t Gabrielle Darley deserving of a second chance? What right had they to splash the worst moments of her life on the screen using her real name? Were they not hindering the upward struggle of an unfortunate? While local courts sided with Davenport, the district court of appeals found that Darley was inherently entitled to privacy. The case still surfaces now and again when the Right to Be Forgotten is being debated.

Presented at A Day of Silents 2018 by Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra