This article was published in conjunction with the screening of Vampyr on January 12, 2024

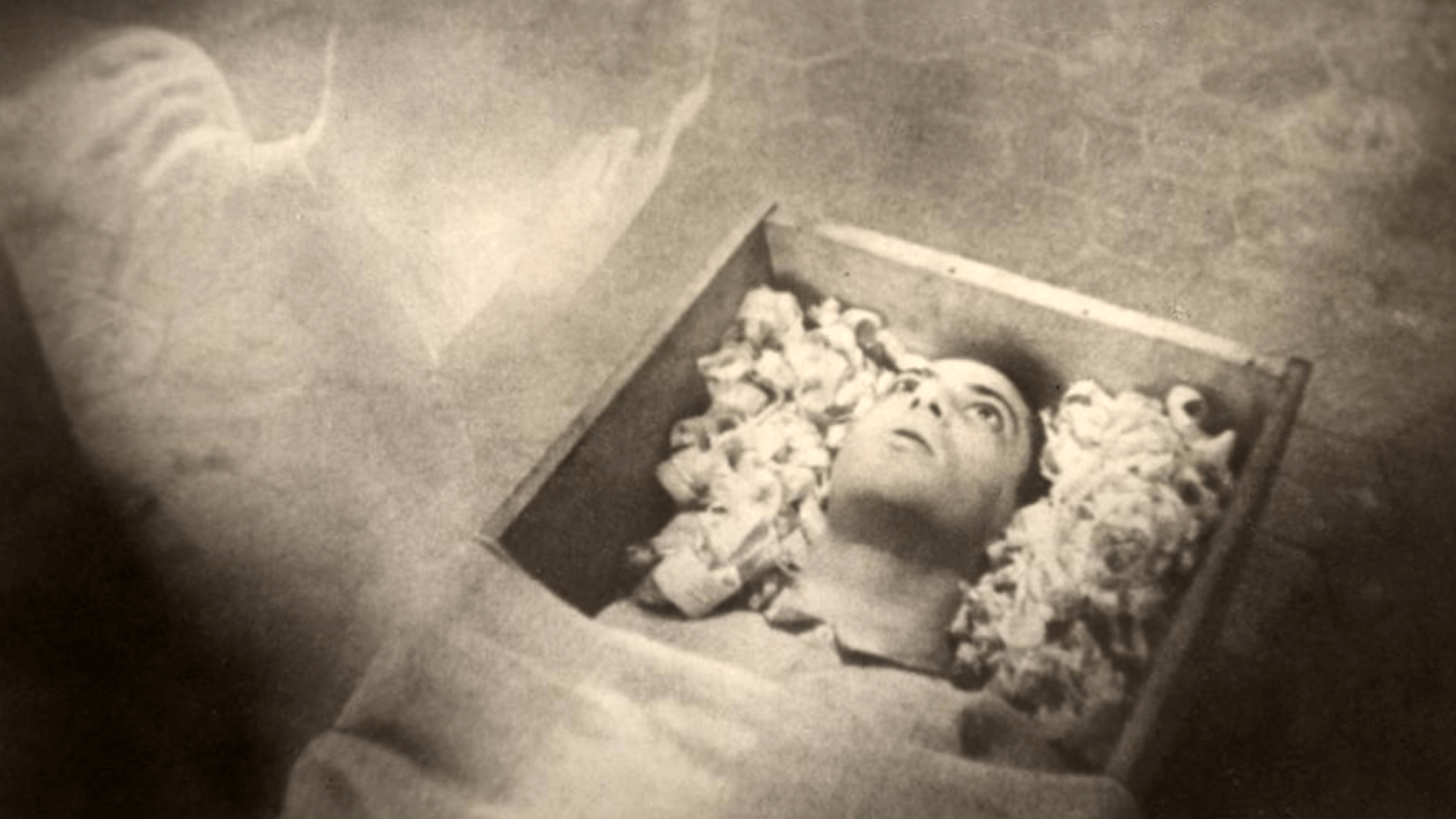

Almost every time one takes a closer look at a film that is world-famous one has to face the sad fact that the film does not really exist in a form that seems acceptable. This is true also for Dreyer’s Vampyr.

The original elements (i.e., camera negative for the image and sound negatives for the three original soundtracks in German, French, and English) are presumed lost. There are a number of original prints left (i.e., nitrate prints of the German and French versions struck in 1932 from the original negatives), but wear and tear over several decades have made them incomplete and quite damaged. Worse, most of them have subtitles, very much against Dreyer’s concept—to ensure widespread distribution, he produced the film with three different soundtracks so as not to disrupt the images with text.

Previous duplications did not do justice to the extremely delicate sfumato images or to the con sordino sounds captured on the variable density track. Some of the existing prints (nitrates or safety duplicates) are bastards, representing not one integral version, but a mix of two, or even three of the original versions, compiled in a desperate attempt to somehow restore the complete film out of elements that didn’t really belong together. Not much seems to remain of the English version, except what’s included in the version distributed by American collector Raymond Rohauer in the 1960s, which we did not have access to, and another bastardization from the 1930s titled, Castle of Doom, which we were not aware of at the time.

Dreyer shot the film in France, edited it, and then brought it to Berlin to post-synchronize it in German, French, and English. Though shooting silent, he had made alternate takes of the few scenes with the actors speaking in the three languages. From what we can detect from the few surviving original prints, there was only one original image negative, which was printed, and then changed by cutting out the dialogue scenes of the first language (presumably German), splicing in the alternate takes, then printing again, and so forth until a sufficient number of prints was produced in all languages. Obviously, this archaic technique, probably due to the extreme poverty of the production company, presented problems whenever a new print had to be made. Any change in the image negative presented a risk of losing the synchronism with not only one, but three sound negatives.

Complicating matters, the German censor required trims to the scenes with Allan and the servant driving a stake through the vampire and of the suffocation of the doctor, which shortened the last reel of the German version by fifty-four meters. The cut scenes survive in the French version but are impossible to reinsert into the German one, because the continuity of images and sounds is different. Thus it was decided to preserve the longer French ending on a separate reel.

Many questions about the integrity of the surviving versions remain, however. Every reel of the German version, for example, is still missing twenty to thirty meters, which adds up to nearly an entire reel of missing footage. Why then does the film still seem complete, after one has put the surviving scenes together, as we have done? We can only speculate. My personal opinion is that Dreyer reworked the film entirely in the process of fulfilling the censor’s requirements. Most likely larger pieces from the previous edit and sound mix were kept, and that would explain why some of the music-changes are rather abrupt in the recorded score and occur in all versions at the same point. Another possibility is that he chopped out entire scenes after the audience booed at the film’s Berlin premiere. There is an article in the trade paper, Film-Kurier, suggesting that such an operation took place as early as after its first two showings on May 6, 1932.