You can read the program essay for our 2000 screening of The Wedding March here

Few people in the history of Hollywood have been as revered and reviled as Erich von Stroheim. Among studio magnates like Irving Thalberg, Stroheim’s inability or unwillingness to deliver a film at a usable length anywhere near on budget made him a hated burden. But the undeniable power of his cinematic vision and his charismatic personality made his movies enormously appealing to audiences and critics alike. His career was a succession of dazzling successes as well as misunderstood, unreleaseable projects hacked to pieces by studios whose idea of a film was 90 to 120 minutes long and bled black ink, not red.

Stroheim came to America from his native Austria, arriving at Ellis Island in 1909 at age twenty-four, where this son of a Jewish hatmaker changed his name to the aristocratic-sounding Erich Oswald Hans Carl Maria von Stroheim, inventing a past for himself as an Austrian nobleman with a distinguished military career. He came to the Bay Area for awhile, living in Mill Valley and Oakland, pondering his life path, then moved to Los Angeles, where he caught on as a Swiss army knife who happened to be an expert on European aristocratic and military matters. His first jobs were as an actor in small but noticeable parts and, in 1914, as an advisor to D.W. Griffith, whom he always considered to be his mentor.

“Throughout his career, he was able to talk people into almost anything,” writes biographer Richard Koszarski, and, in 1919, Stroheim talked his way into directing and starring in his first film, Blind Husbands, at Universal where noted penny-pincher Carl Laemmle was willing to gamble on anybody with a good idea who didn’t need to be paid too much. The film was a smashing success, critically and commercially. In one stroke Stroheim established himself as the most sophisticated filmmaker in Hollywood.

Stroheim was notorious for his lavishness and extravagant staging, with an obsessive attention to the intricate details of costumes and set design. He went to the set with an approved script but felt no hesitation in creating new scenes as he went, oblivious to running time or expense. In the case of Greed, this work style resulted in an eight-hour final cut. Naturally, this led to a studio butchering of the print to two hours, which made the film incomprehensible and assured its failure with audience and critics. But his methods were not driven by incompetence or ignorance. They were conscious choices. He was creating a new kind of cinema.

“My single aim in directing a picture is to give plausibility to the picture,” he said in a newspaper interview when quizzed about his extravagant production methods. “I try to make the members of the cast live their parts, be the characters that they are playing … It is because I forbid theatricality, refuse to allow them to act all over the place, that they become natural and interpret their roles by living.” That plausibility involved meticulous attention not only to building characters but also to the sets and costumes they inhabited.

More than once Stroheim lost control of a picture before it was finished. His sixth film as director, The Merry Widow, was thought to be his last chance to show that he could play by the rules. But it fared no better than the others. He was thrown off it by MGM in an attempt to stem the bleeding. But in a stunning reversal of fortune, instead of losing money, The Merry Widow became his greatest commercial and critical success.

The major studios professed to be through with him, but an independent producer, Pat Powers, stepped up to make a deal in conjunction with Paramount. Stroheim would write an original story, direct, and star. The project was to be titled The Wedding March, a romantic drama set once again in the twilight of the Hapsburg dynasty in pre-World War I Vienna, as most of his films were.

The Wedding March is a vindication of Stroheim’s approach to realism. Without the crowd scenes, the lavish celebrations and costumes, the establishing of the decadent lifestyle of the aristocracy, the emotional punch at the end of the story would not be so strong. The story centers around Prince Nicki (Erich von Stroheim), the son of a noble family who has been living the life of a cynical libertine and is now in financial straits. When he goes to his father, Prince Ottokar (George Fawcett), for money, Ottokar tells Nicki that he has nothing. He advises his son to “marry money” and save the whole family.

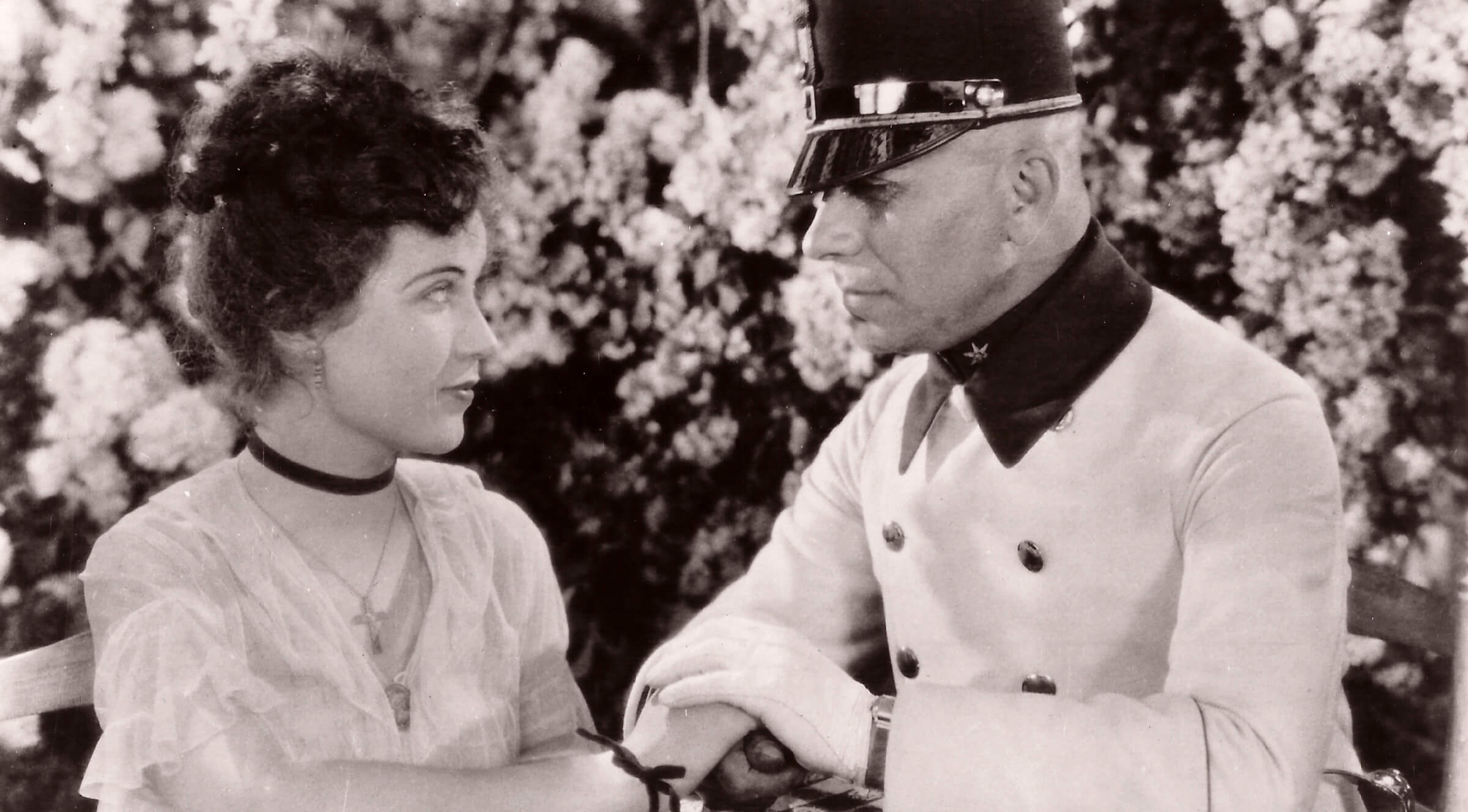

At the Corpus Christi religious parade in front of St. Stephen’s Cathedral, the dashing Nicki, on horseback in his cavalry commander’s finery, notices a beautiful young woman, Mitzi (Fay Wray), in the crowd. They exchange meaningful glances, even though she is with the loutish Schani (Matthew Betz), who has designs on marrying her. After a disturbance, Nicki has Schani arrested, and the mutual hatred and jealousy between them is ignited. But Nicki and Mitzi keep meeting under romantic circumstances and fall in love.

Nicki is approached by a wealthy capitalist to marry his daughter Cecelia (ZaSu Pitts): a million-dollar dowry in exchange for a noble title for her. Nicki initially refuses but finally relents; it is his duty as a nobleman to save the family from humiliation. When Schani is released from jail he angrily tells Mitzi what a fool she is to harbor illusions of marrying a nobleman. He plans to kill Nicki at the elaborate royal wedding. He waits for Nicki with a gun outside the church. Mitzi promises to marry Schani if he refrains from his attempt to kill Nicki. Oblivious to all this, Nicki and Cecelia get into their coach and drive away as he wipes a tear from his eye. The pain in his heart is understated but obvious.

The casting was easy, as Stroheim turned to actors he had been working with for years. In the role of Cecelia he cast Pitts, a comedienne already known for her goofy persona whom he had turned into a dramatic leading lady in Greed. And of course he cast himself in the lead role, Prince Nicki. The one role that remained difficult to fill was that of Mitzi. After seeing hundreds of candidates, he instantly connected with Wray. At the age of eighteen, she had the unspoiled starry-eyed beauty he was looking for. It was her breakthrough part and led to a notable career.

From the beginning Stroheim was thinking of a two-part film: The Wedding March, which would end at the wedding, and The Honeymoon, which continued the story. Stroheim’s extravagance was, as always, legendary. He had a reproduction built of the Vienna cathedral. For a romantic scene in which Nicki and Mitzi meet in a luminous apple orchard at night, he had thousands of apple blossoms tied by hand to the trees. An orgy scene among the aristocrats was enhanced by call girls and bootleg gin brought onto the set; the shooting went nonstop for days. It was no surprise that Stroheim’s cut ran to six hours. Powers took the film away from him and, after a series of misfortunes, it was made into two films after all, both of them unsuccessful. (The only known surviving print of The Honeymoon was lost in a fire at the Cinémathèque Française in 1959.)

The Wedding March is perhaps Stroheim’s most personal film. In an interview with Hollywood Filmograph magazine he said, “The Wedding March is an expression of my own homesickness, the nostalgia of one who revives dear memories with a catch in his throat and a pain in his heart.”

Presented at SFSFF 2019 with live music by Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra