This feature was published in conjunction with the screening of No Man’s Gold at SFSFF 2018

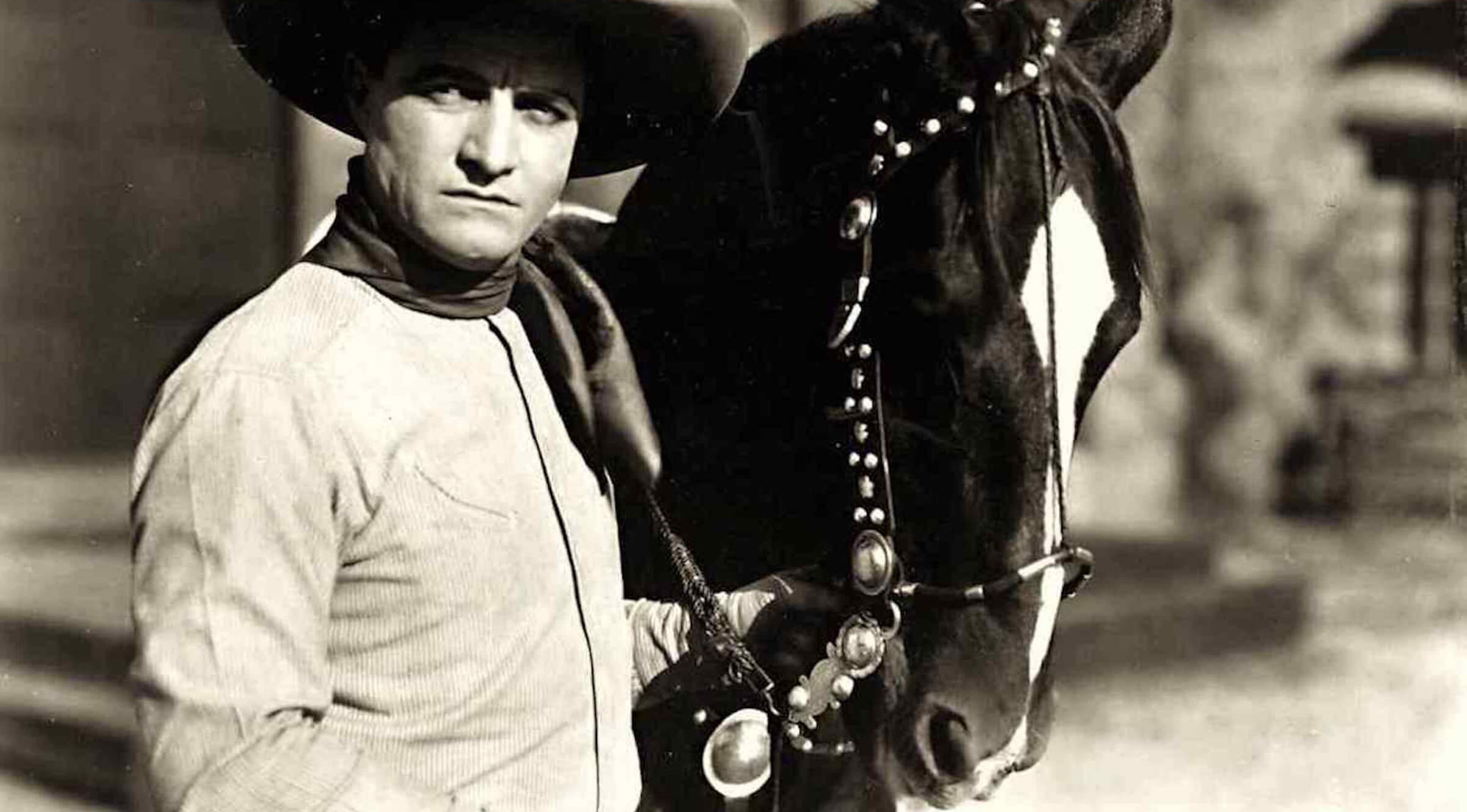

Not for nothing these popular, if often cheaply made, westerns were nicknamed Horse Operas, requiring of actors one paramount skill, ridership, or at least the ability to sit convincingly in the saddle—even better if you could do tricks, which as a veteran of the touring western shows Tom Mix could. But a cowboy’s only as impressive as his mount. Mix was still at Selig Polyscope for his first film to cast Tony, 1917’s The Heart of Texas Ryan, but the sorrel marked with a diamond-shaped blaze and two hind stockings didn’t replace Mix’s regular steed Old Blue, until the brown gelding broke his leg in 1919 and had to be put down. Bought for six hundred dollars off Pat Chrisman, a frequent extra in Mix’s westerns, Tony eventually became just as big of a draw as his rider in the pictures made for the Fox studio.

TRAILIN’ (1921)

A bridge gives way under Mix and Tony, Courtney E. White writes in The Historical Animal about the film’s uncut footage, and then both are seen “tipping” into the water below. An unusual role for Mix who trades in his spurs for jodhpurs, Trailin’ offers an aristocrat’s reason to ride, the fox hunt—but in these scenes a stunt double took Tony’s place. Maybe it was Black Bess, a large mare (with Tony’s markings sometimes painted on) used for long distance shots because she cut a better figure than Tony did from faraway.

FOR BIG STAKES (1922)

For the trades and audiences alike Tony the Wonder Horse could be the main attraction in Mix films. In its review, Photoplay dismissed For Big Stakes as “programmer stuff” but saved space for Tony: “His horse got the largest amount of applause—and deserves it more than any other member of the cast. Take the children—they won’t be critical and they’ll enjoy the horse.” It helped that Tony was heavily marketed, in publicity shots (once getting a manicure and a wave for his mane), with tie-ins such as paper dolls, and later a children’s book—1934’s Tony and His Pals, written as if by the horse himself.

JUST TONY (1922)

Tony reportedly got his own fan mail (along with blankets and boxes of sugar cubes), once receiving a letter addressed to “Just Tony, Somewhere in the USA.” Just Tony is also the first of three films named for the horse actor and Film Daily approved of his first time at center stage: “Tony has long been a familiar and important figure in the Tom Mix features, but this time he goes it alone, acquitting himself capable at all times.” Variety seems to genuinely marvel at the stunts: “How they ever kept a camera near the rough and tumble is hard to figure out.” A Photoplay columnist disagreed completely but still managed to elevate Tony: “Somebody said of this picture that it was acted by a horse but unfortunately not written by one.”

THE GREAT K & A TRAIN ROBBERY (1926)

Directed by No Man’s Gold’s Lewis Seiler and shot on location, this railroad detective story incorporates Colorado’s stunningly steep canyons into the action and features Tony holding, as one review states, “a large share of the interest” with some “remarkable stunts, working by himself on quite a few occasions.” Fifteen minutes in, before leaping out a hacienda window into the drink then over a fence, all while carrying two riders, Tony is tethered to a caboose, available for Mix to hop on and ride to save another day. It’s rather nonchalantly done but seems a particularly reckless thing to ask of a horse.

THE BIG DIAMOND BANK ROBBERY (1929)

Tom’s after the bad guys once more in Tony’s last picture before retiring to Mix’s ranch. He was already out to green pastures when he was billed as the mount in the cowboy star’s first sound picture, Destry Rides Again (1932). (His replacement, Tony Jr.—sporting four stockings—was passed off as Tony the Wonder Horse until the fall of 1932.) Although he made films before any oversight protected animal actors in the picture business, Tony was well looked after—a dynamite incident on 1923’s Eyes of the Forest put both star and rider out of commission temporarily but apparently was Tony’s most significant injury over his dozen years on film. As The Historical Animal assures, “Horses rarely survived to such advanced ages in captivity without modern veterinary care.” Tony lived two years beyond his owner, dying in 1942 at the then-ripe-old-horse age of thirty-two. His death was reported in the New York Times.