One of the outstanding examples of the mid-twenties golden age of German cinema, Ewald André Dupont’s Varieté has a plot that would work nicely for a late-forties film noir, complete with an alluring femme fatale, betrayal, and death. It begins in a bleak prison where Boss Huller (Emil Jannings) is about to finish serving a ten-year sentence for murder. For the first time he confides to the warden the true story behind his crime. Even though he is finally being released, he has little to look forward to on the outside. Before his arrest, Boss had destroyed everything that ever meant anything to him.

Once a celebrated trapeze artist, Boss has been reduced to running a low-grade peep show and carnival with his devoted wife and their small child. One day an exotic-looking young woman, Berta-Marie (Lya de Putti), “just arrived from Frisco,” hopes that they will hire her as a side-show dancer. Frau Huller feels threatened, but Boss says, “She stays.” Berta-Marie’s hoochie-coochie dance drives men wild, Boss included. Before long he has fallen madly in love, and they run off together.

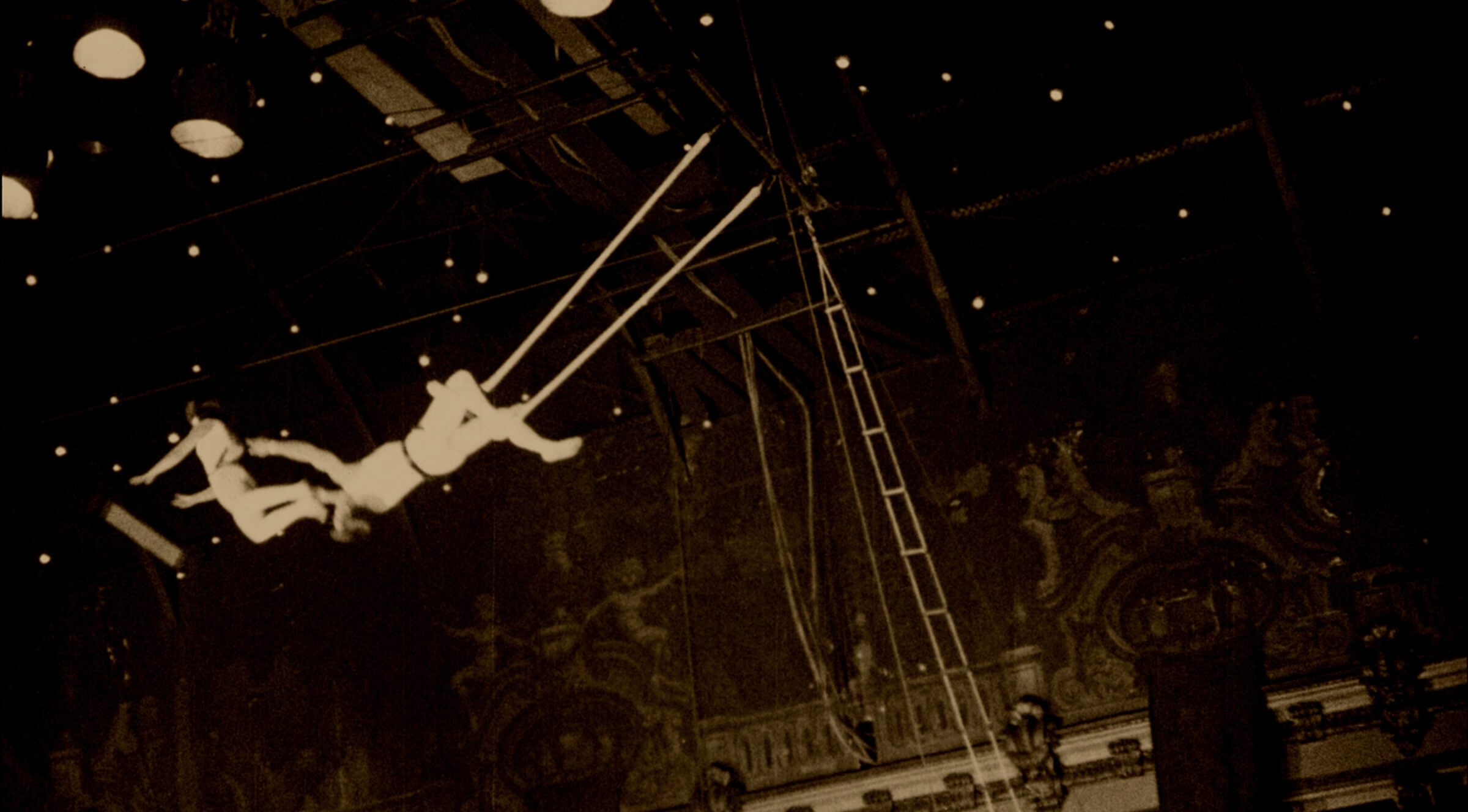

Boss forms his own trapeze act with Berta-Marie and, back in the limelight and in love, is living a dream. Their act has drawn the attention of a famous trapeze artist, the suave, elegant Artinelli (Warwick Ward) who hires them to be his new partners. It doesn’t take long for Artinelli to use his charm and a little sparkling bling to seduce Berta-Marie. Boss is consumed with jealousy, and the bond among the trapeze artists, whose very lives depend on their complete trust in each other as they fly through the air and into their partners’ sure grips, is shattered.

Varieté was one of the signature productions of the German film studio Ufa, which in 1925, was at the peak of its legendary reputation. The studio was formed by the German military in 1917 to produce propaganda films in the last years of World War I and, after the war, became quickly known as a center of the utmost professionalism and innovation in motion pictures. These years coincided with the all-too-short days under the Weimar Republic during which German art and culture flourished. In cinema these were the early years of Ernst Lubitsch, F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, and E.A. Dupont. Pola Negri, Emil Jannings, and Marlene Dietrich became world famous stars. Ufa’s reputation was such that a young Englishman by the name of Alfred Hitchcock found himself directing his first feature there, learning everything he could from the masters of photography and the nuances of visual drama.

E.A. Dupont began as a screenwriter and directed programmers, mostly detective stories from his own scripts. His breakthrough came with two films featuring Henny Porten, The Green Manuela (1923), about a young dancer who falls in love with a smuggler whose brother gives his life to ensure their happiness, and Das alte Gesetz (1923), the story of a young Jew’s flight from his orthodox home to seek fame in the theater.

In Varieté, which the director adapted himself from the 1921 novel by Felix Holländer, Dupont best demonstrated his thorough grasp of the medium. In her influential 1952 book The Haunted Screen, Lotte Eisner describes “the secret of Dupont’s talent.” She writes, “He has the gift of capturing and fixing fluctuating forms which vary incessantly under the effect of light and movement. His objective is always and everywhere the ebb and flow of light.”

In his 1947 book From Caligari to Hitler, Siegfried Kracauer points to Dupont’s talent for revealing the hidden motivations of his characters. “Unusual camera angles, multiple exposures, and sagacious transitions help transport the spectator to the heart of the events,” writes Kracauer on how Dupont deftly opened a window onto “the psychological processes below their surface.”

For Varieté Dupont was able to gather the greatest talents of German cinema, beginning with the leading man, Emil Jannings, fresh off his virtuoso performance in The Last Laugh (1924), which cemented his reputation as the country’s greatest actor. Jannings had the ability to make himself the rock-solid center of a film, whether as the lowly doorman in F.W. Murnau’s film or the beaten-down Professor Immanuel Rath in Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel (1930). Already well-known and admired for his earlier German films, Jannings came to Hollywood in 1926 on a contract with Paramount and had even greater success, garnering the first ever Best Actor Academy Award for his appearances in Victor Fleming’s The Way of All Flesh and von Sternberg’s The Last Command.

Lya de Putti, a sultry, Hungarian-born former dancer, was perfectly suited for the part of the young temptress Berta-Marie, making a credible transition from cowering, orphaned teenager to adept seducer. The attention earned her a Hollywood contract, where she was mostly cast as vamps. The fan magazine Picture-Play gushed about her performance in Varieté. “Lya de Putti is a seductress the like of which the screen has never yielded from the long line of native sirens. She is baleful, unbridled—as naïvely physical as a quadruped of the jungle.” De Putti also worked on the New York stage and made other films in Europe but died at thirty-one after a so-so stateside career.

The behind-the-scenes talent who contributed most to the visual artistry of Varieté was cinematographer Karl Freund, that mad scientist of the camera. As Kracauer points out, the camerawork for Varieté had its dress rehearsal in The Last Laugh, shot the year before. Freund tried everything possible to give his films a distinctive look, especially with the use of movement, and his characteristic unleashed camera was uniquely suited to the high-flying action in Varieté. The camera moved everywhere, on vehicles and in the streets. He even attached a camera to the swinging trapezes of Boss, Berta-Marie, and Artinelli, for a vertigo-inducing point of view. After Varieté, Freund shot Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, another unparalleled achievement, and was one of the photographers of Walter Ruttmann’s avant-garde Berlin—Symphony of a Great City (1927), for which he developed a high-speed film stock that made shooting outside at night without artificial lighting as feasible as shooting during the daytime.

The film achieved considerable critical and popular success in America. “However the public may have received the Ufa picture Variety, it had a tremendous effect on Hollywood,” wrote an excited columnist in Picture-Play. “Directors, scenario writers, producers, and actors have seen the picture as many as half a dozen times and one may expect to see many varieties of Variety on the screen shortly.”

The principal creative artists of Varieté took advantage of the opportunities this success offered. Dupont directed the Viennese period piece at Universal, Love Me and the World Is Mine, which was inexplicably shelved until 1928, when it fell flat with audiences and critics. He had better luck in Britain, where he made two other films set in a show-biz demimonde, Piccadilly and Moulin Rouge. Despite his monumental talent, his was a sadly underappreciated career.

In his book E.A. Dupont and his Contribution to British Film, Paul Matthew St. Pierre describes a portion of Dupont’s considerable achievements: “He made the first movie, Atlantic, about the sinking of the Titanic. He cast Anna May Wong in her first starring role in an English-language movie, after she had made 30 films in America, all in stereotypical Asian supporting roles; Piccadilly established Wong as a lead actor in the movies. In Two Worlds, Dupont was one of the film filmmakers to depict not only a pogrom but also Jewish armed resistance to it during the First World War.”

Presented at SFSFF 2016 with live music by the Berklee Silent Film Orchestra