In his epic multivolume Histoire du cinéma, French film theoretician and historian Jean Mitry wrote, “If I had to choose one film of all the French productions of the 1920s, it is undoubtedly Visages d’enfants I would save … It is the only one that is still modern today.” That was written more than forty years ago, but director Jacques Feyder’s striking imagery and the subtlety of the performances remain breathtakingly modern.

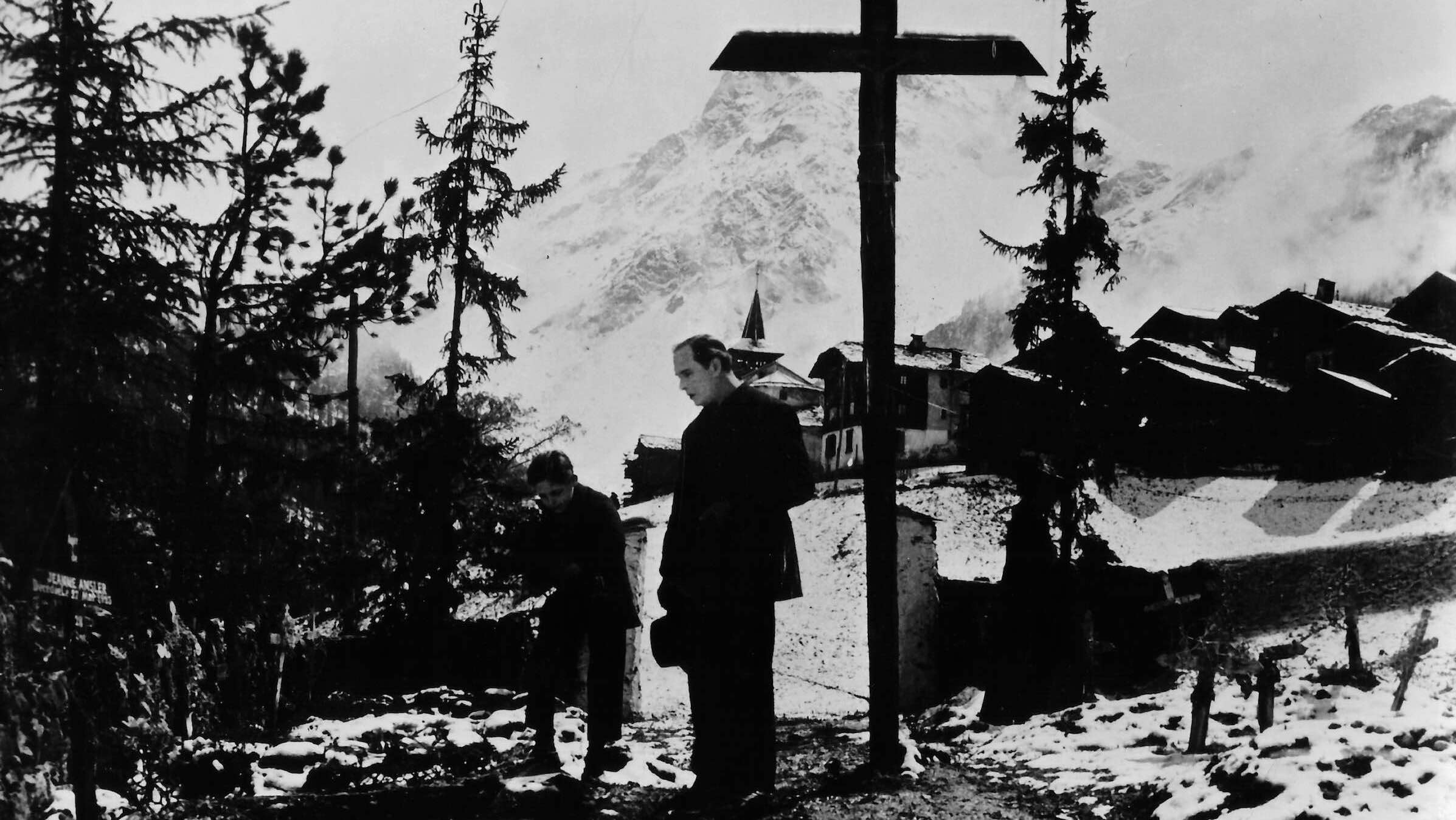

Set in a village in the Swiss Alps, Visages d’enfants (literally, “Faces of Children”) begins with the funeral of the mayor’s wife, who has left behind two children, ten-year-old Jean, and his little sister Pierrette. In the film’s remarkable opening, the casket is brought down the stairs from the bedroom, as Jean watches, heartbreak visible on his face, and Pierrette, uncomprehending, plays. The eleven-minute sequence continues with the procession to the cemetery; and finally, Jean’s collapse at the gravesite. The boy is devastated by the loss of his mother and, a year later, is still mourning. Meanwhile, his father proposes to a local widow who has a daughter of her own. Concerned about how his grieving son will react, the father sends Jean on a trip with his godfather, the local priest. Jean returns to find his new stepmother and stepsister ensconced in the family home, where conflicts are inevitable. It is a simple story, beautifully told, and marks a turning point in the Belgian director’s career.

Born Jacques Léon Louis Frédérix in 1885, Feyder moved to Paris at the age of twenty-five and pursued an acting career first onstage and later in films. He began directing in 1916 and made his first major feature, the ambitious, if ponderous, three-hour epic L’Atalantide in 1921. Feyder spent eight months on location in the Sahara shooting the fantasy about a French Foreign Legionnaire and the mythical Queen of Atlantis. It was the most expensive French production to date.

Critics were not kind, and for his next film, Crainquebille (1922), Feyder returned to real-world Paris for the story about an elderly vegetable peddler who becomes a neighborhood outcast and the homeless urchin who idolizes him. To play the boy, Feyder discovered nine-year-old Jean Forest living on the streets of Montmartre, where the film was shot. Crainquebille is an early example of the poetic realism that characterized much of Feyder’s work and also features some experimentation with the German expressionist style.

As he was preparing his next film, Visages d’enfants, Feyder wrote an article for an Austrian film magazine about how European filmmakers must produce movies with international appeal. In it, he notes that the worldwide success of American productions is a paradox: “These films, aiming only to please the American public, have known the greatest and most durable success the world over,” and concludes, “Only a film of high national character is truly an international film.” He cites the Swedes, “who have created the most beautiful films in the world” while “never producing anything but Swedish films.” Feyder’s ideal films have a picturesque natural setting and “a simple story, an event that speaks to all intelligences, to all hearts.” Crainquebille, with its colorful city market, and Visages d’enfants, with its Alpine village vistas, combine with the emotional honesty of their stories to fit Feyder’s filmmaking prescription. But the production of Visages d’enfants was challenging, its road to becoming a milestone of French cinema was as steep and rocky as a mountain path.

Funding came from two Swiss investors who wanted to promote the Swiss film industry and show off the natural beauty of the country. Feyder and his crew shot exteriors in the Haut-Valais region of the Alps, in southwestern Switzerland (all the interiors, along with additional exteriors, were shot on studio sets in Paris). The schedule called for two months of location shooting in the spring of 1923 but lasted four months because of the difficulties posed by the rugged, remote site. Cinematographer Léonce-Henri Burel, who had shot Crainquebille and often worked with Abel Gance, captured the magnificence of the region, as well as the isolation and danger of nature. The changes of season also reflect the changing emotions of the characters, with the father’s grief in winter abating as spring arrives. The use of vast landscapes and nature recall those of the Swedish directors Feyder so admired, Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller.

Locals, many of whom had never seen a movie, or even a camera, appeared as extras, adding authenticity to scenes such as the funeral procession and the wedding celebration. The young actors who played the children were spontaneous and natural, and Forest proved that his fine performance in Crainquebille was no fluke, delivering a powerful and moving portrait of a troubled boy. Forest later costarred with Feyder’s wife Françoise Rosay in the director’s lighter film about childhood, Gribiche (1926), and appeared in several more films over the next decade. When his film career faded, the young actor went on to a long career in radio. Rosay cowrote the scenario for Visages d’enfants, and directed some scenes during production in Paris when Feyder had to go to Vienna to set up his next project.

Cost overruns on Visages d’enfants only added to Feyder’s reputation as a profligate filmmaker that he had earned while making the epic L’Atalantide. Trying to secure better distribution for their films, Feyder and fellow directors Max Linder and René Hervil teamed up to form a distribution company, Les Grands Films Indépendants. But after shooting on Visages ended, Feyder clashed with the company administrator, who impounded the footage. The company held the film for several months and, by the time they released it, Feyder was working on another project. It was a year before he was able to edit Visages d’enfants.

The film finally opened in March 1925. Critics hailed it as a masterpiece, but it was not popular with the public. It was considered a failure, although it did receive international distribution, thanks to the good reviews. Japanese critics named Visages d’enfants the best European film of the year. Over the years, the film’s negative disappeared, and no good print existed until the Royal Belgian Film Archive restored it in 1986. New restorations were made in 1993 and 2004.

Jacques Feyder’s “career zigzag,” as film historian Lenny Borger labels it, took him to Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Munich, Hollywood (where he directed Garbo and Ramon Novarro), and London. He earned the most acclaim for his masterpiece of poetic realism, Le Grand jeu (1934), and La Kermesse héroïque (1935), a historical satire about a Flemish town occupied by invading Spaniards, which the Nazis banned in 1940 soon after taking over Paris. Feyder and Rosay fled to neutral Switzerland, where they lived until his death in 1948.

In the decades since he died, Feyder’s work has been forgotten, reviled (by Cahiers du cinéma critics such as François Truffaut), ignored, lost, and rediscovered. The restoration of his best films, among them Visages d’enfants, has revived his reputation as well. In 1944, Feyder and Rosay published Le Cinéma, notre métier, an autobiographical memoir of their films together. In it, Feyder wrote that he regarded himself simply as an artisan, a craftsman of filmmaking “in the full sense of the word, both honorable, and limited.” Today, many cineastes would disagree. Not only was he an artist, he was a true auteur long before the same Cahiers critics who had disparaged him proclaimed the auteur theory.

The 2015 San Francisco Silent Film Festival Award was presented to Serge Bromberg of Lobster Films at this program.

Presented at SFSFF 2015 with live music by Stephen Horne