Published in conjunction with the screening of Kentucky Pride at SFSFF 2023

“Can you ride?”

An acting manual from 1922 warned wannabe movie stars that this would be among the first questions asked when they applied at motion picture studios. As a matter of fact, there was every chance that a new actor’s big name costar would have four legs, hooves, and a taste for sugar cubes.

During the 1910s, the best loved horse-cowboy bromance of the screen was between hard-bitten, fist-fighting two-gun Good Bad Man William S. Hart and his pinto pony, Fritz. Fritz was small but mighty, demanding his own entourage, consisting of a mustang named Kate and a mule named Lizbeth, and allegedly penned his own book—though Hart did admit to editing it. Hart was eventually able to purchase Fritz from the studio and took him into retirement with him when he bid farewell to the screen.

Tom Mix, the flashiest of the celluloid cowboys and genuine veteran rodeo star, rode Tony, who had a distinctive white blaze and was as stylish as his owner. Tony was touted as a “Wonder Horse,” a title shared by many cinema steeds, but no other animal enjoyed billing alongside Mix. Meanwhile, John Ford’s original leading man, Harry Carey, was dustier, gritter, and devoted to Pete, a dapple-grey who went home with Carey to his ranch when they weren’t working. Smaller names in the western game also showed off the antics of their signature mounts. Ken Maynard’s Tarzan was billed as “endowed with super-intelligence.” Jack Perrin had Starlight, a white horse with a playful side whose talents included politely knocking on doors to gain entry.

Other rodeo veterans turned movie stars rode their favorites as well. Bill Pickett, a legendary bulldogger who made two films for the Norman Film Company in the 1920s, was partnered with an equally fiery horse named Spradley. Trick rider Helen Gibson was having difficulty finding the right horse for her film work, so the Kalem film company bought Black Beauty, her former mount, from the western show that owned him.

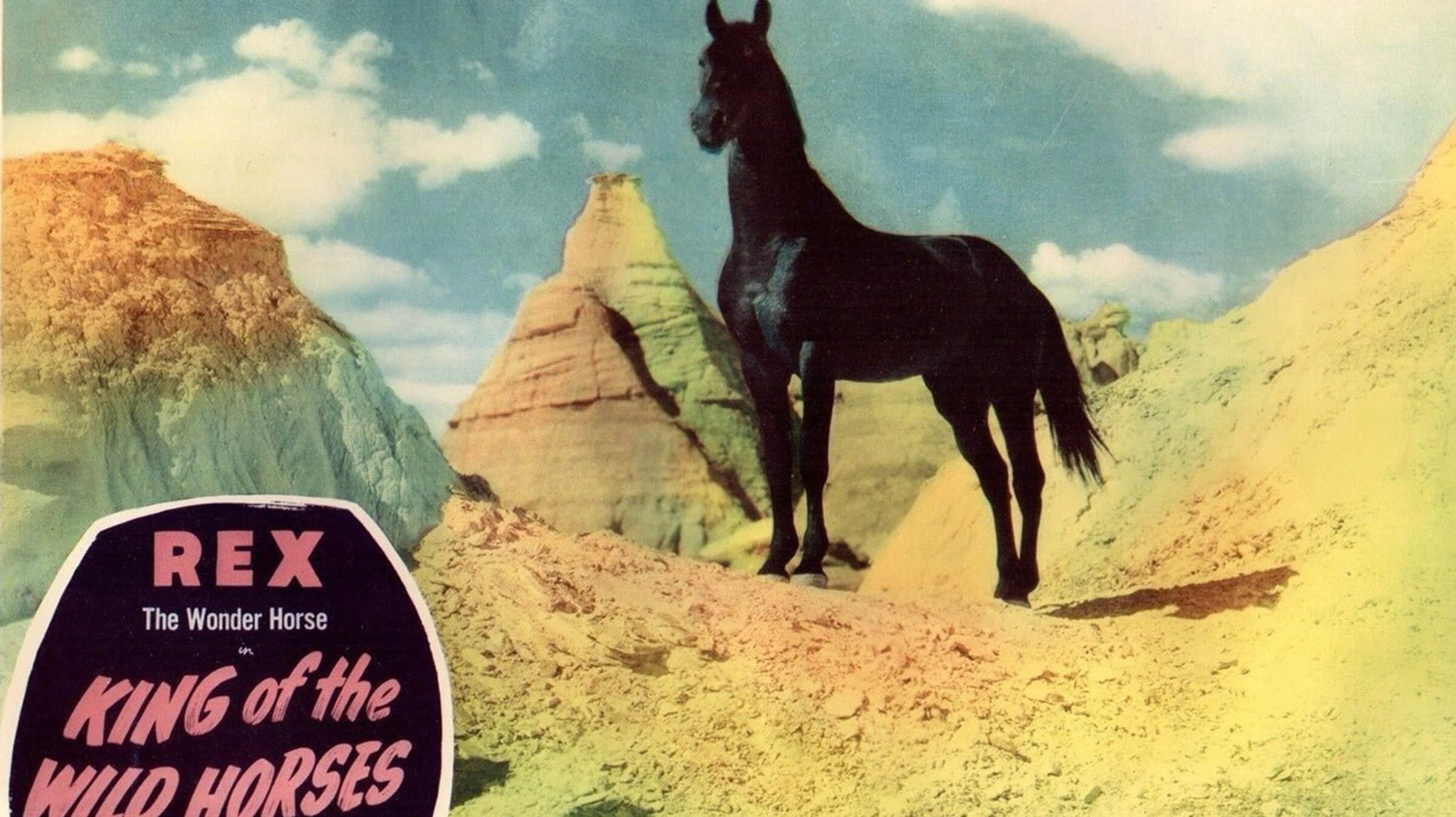

Rex, who caused a sensation in King of the Wild Horses, belonged to no cowpoke and was a superstar in his own right. He was a black Morgan so charismatic that he was bestowed an “IT” title by author and hoopla queen Elinor Glyn, sharing the distinction with Antonio Moreno, Douglas Fairbanks, John Gilbert, and, of course, Clara Bow. In an interview, Glyn pointed out that, unlike human beings, Rex was unlikely to ever lose “IT” as being casually unaware of one’s own sex appeal was the secret of keeping it.

Rex wasn’t the only example of a standalone equine star. Just as boxers, baseball greats, surfers, and track stars were referenced, cameoed, or even starred in silent films, celebrity racehorses were accorded similar respect. Famous champions Man o’ War, Fair Play, Morvich, and The Finn were featured in Fox’s Kentucky Pride and “Us Horses” were billed before their human costars. Man o’ War also enjoyed solo recognition in his own self-titled 1920 short, which touted him as the “Wonder Horse of the World” and the film as “a delight to women, children and all horse lovers.” Just weeks after Kentucky Pride was released, Universal announced that it had obtained the services of three notable racehorses: two bay geldings named Last Chip and Short Change and a third horse named Jack Lee. “Track Stars Forsake Tia Juana for Films!” Universal Weekly’s headline screamed.

The similarities between human and horse stars didn’t stop there. A fan magazine fashion piece described Helen Holmes’s riding habit in loving detail and the rig of her horse, Rocket, was given equal consideration. He wore a smart browband of white patent leather accented with red. Antonio Moreno may have had “IT” but magazine glamor shots of his horse, Salano, gave both Moreno and Rex a run for their money. Beautiful people on beautiful horses proved to be an irresistible combination for the press of the era.

If equine stars shared the rewards of their human counterparts, they also shared the downsides. For every superstar horse, there were hundreds of unnamed extras and the film industry cared even less for their safety. A breathless American ad for the 1913 Italian version of The Last Days of Pompeii proudly proclaimed, “Five Horses Killed in Chariot Scene!” The pattern tragically repeated as four human extras and forty horses were reported killed during the 1926 shoot for Beau Geste in Yuma, Arizona, and it was hardly the exception. For all of its affectionate title cards, Kentucky Pride seems to have made use of the often deadly (but routine) tripwire to stage its leading horse’s fall before the finish line.

Film producers found themselves grappling with activists determined to force the movie moguls to look after the well-being of their animal performers, particularly horses. In 1924 the American Animal Defense League organized a protest, instructing patrons to buy tickets to horse pictures and then walk out, citing cruelty as the reason. Targeted films included King of the Wild Horses, The Covered Wagon, and The Ten Commandments. Producers countered that the group’s actions were both libelous and slanderous and threatened to take legal action. Real reform was still years away.

There were some cases of motion pictures doing good. A 1916 fan magazine recounted a particularly vicious Wild West show performing in Cincinnati that mistreated the company horses. Humane officers were able to bring charges because a reporter had taken newsreel footage of the show and volunteered the film as evidence.